From Dalí to DALL-E: A Century of Surrealism

A hundred years ago, surrealists pioneered a philosophy of artistic expression dictated by thought, absent of reason, and exempt from aesthetic or moral concern. Is GenAI the answer to Surrealism’s’ quest for pure connection to our deeper consciousness?

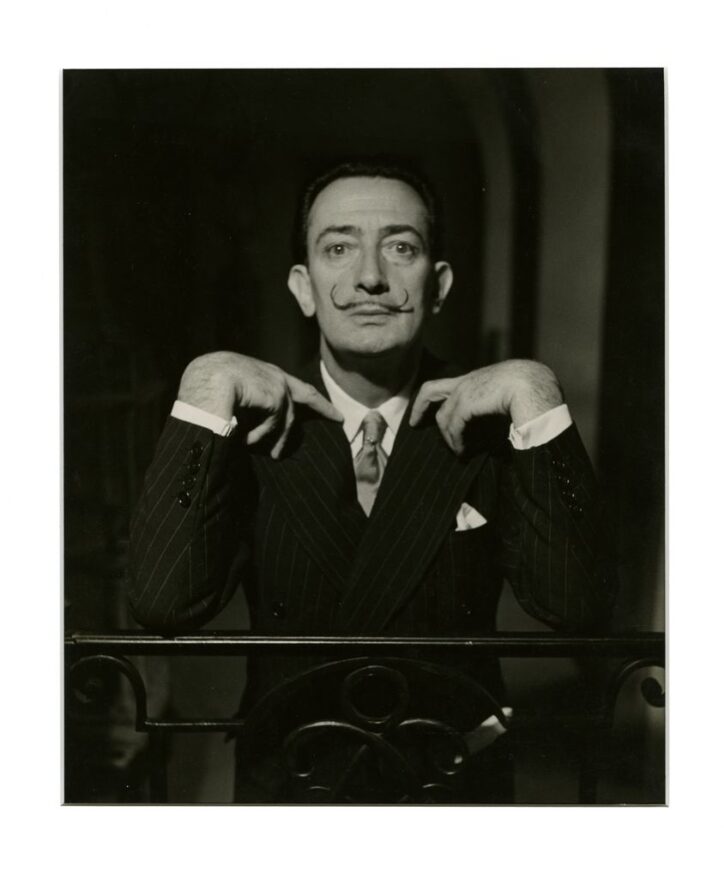

Surrealism, the revolutionary art movement of the 20th Century that inspired iconic artists like Salvador Dali and Frida Kahlo, celebrates its 100th birthday this year.

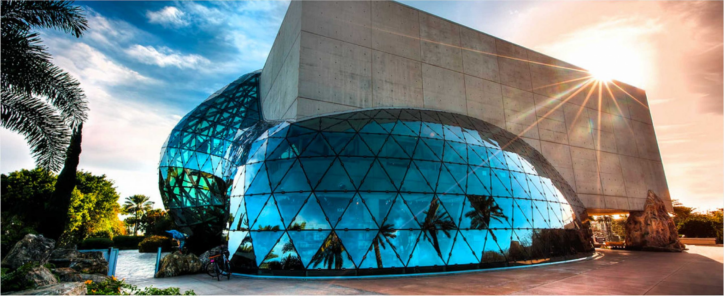

The Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, FL, is commemorating Surrealism’s Centennial by bringing the iconic surrealist, who believed he would never die, back to life. The Museum is launching “Ask Dali,” a chatbot trained on the Spanish artist’s writings and unique voice. Ahead of the launch on April 11, “Ask Dali” and its creator, Martin Pagh Ludvigsen, gave Creativity Squared an exclusive interview discussing A.I.’s impact on creativity, the process of building “Ask Dali,” and how the Dali Museum’s using new technology in other ways to fulfill the artist’s dream of never dying..

Born out of the cynically absurdist Dada movement in post-World War One Europe, Surrealism is art that channels our deepest human psyche and challenges our collective perception of reality. Surrealism is best known from paintings like Dali’s The Persistence of Memory and René Magritte’s The Human Condition, yet its influence appears in art of all disciplines. It was actually a French Author and Poet, André Breton, to pen Surrealism’s founding document.

In his 1924 “Surrealist Manifesto,” Breton defined Surrealism as “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

Breton and his contemporaries were inspired by Sigmund Freud’s theories about multi-layered consciousness, latent desires, and the mysteries of the unconscious mind. Some of the early Surrealists painted hyper-realistic dreamscapes filled with symbolic imagery depicting the “functioning of thought” and their belief that the unconscious mind is the source of imagination. Painters and other surrealist artists like Max Ernst also practiced methods like decalcomania and collage to automate the creation process and remove any “control exercised by reason.”

While the original Surrealist movement fractured and mostly ended around the start of World War Two, Surrealism as a broader genre lived on to influence subsequent art movements, such as Jackson Pollock’s post-war, abstract-expressionist drip paintings. Today, art industry insiders say institutions are curating more surrealist exhibits, famous surrealist works are fetching more at auction, and formerly obscure surrealist artists are now finding a market.

Surrealism’s recent resurgence is more than a birthday celebration. In addition to the efforts at the Dali Museum, Artists like Refik Anadol, Paul Trillo, and Robert Seidel are pushing the boundaries of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism through A.I.-collaborative art.

Surrealists’ Quest for Automatic Creation

Andre Breton was about to fall asleep one night in 1922 when, in the twilight moments before drifting off, a phrase entered his mind that he simply could not shake.

“There is a man cut in two by the window.”

Breton later described this phrase as a symbol of our dual existence in physical reality and the our unconscious mind. At the time, though, he was more interested in how he received the phrase from the depths of his psyche. After hearing those nine words, Breton said he could not get them out of his head and felt compelled to incorporate them into his work, as if he lacked the control to decide for himself.

This experience influenced Breton to experiment with “automatic writing,” which many consider to be the first truly Surrealist method. Automatic writing is stream-of-consciousness, writing thoughts down as fast as they’re formed and before our higher consciousness can put them through quality control. The surrealist artist acts as a passive vehicle, transporting the unadulterated intention to execution.

“Automatism” (as Surrealists called their methods of automatic creation) became a central trend within the movement. By becoming “modest recording instruments” without regard to artistic convention or social norms, Breton and his contemporaries strived to unlock an innate consciousness, reveal the mechanisms of the unconscious mind, and connect humans with their innate selves.

As fascists and communists sent Europe into violent political turmoil between World Wars One and Two, Surrealists saw automatism as a democratizing force. Breton wrote in his 1933 essay “The Automatic Message” that Surrealism deserves credit for recognizing “the total equality of all ordinary human beings before the subliminal message, that it has constantly insisted that this message is the heritage of all.”

The founding Surrealists also believed that creating at the speed of thought leads to better art by preventing our consciousness from filtering our thoughts through lenses of approval-seeking and self-doubt. Through passivity, Surrealists believed that their art could transcend the boundaries of reality and imagination.

Is GenAI the Creative Tool that Surrealists Always Wanted?

Today, generative artificial intelligence allows us to create faster than we can think. You can execute an idea in the time it takes you to type it, and no need for self-doubt because the result will likely be much higher quality than what your skill could have created. There are also parallels between Breton’s belief in the collective unconscious and the nature of a large language model, which is trained on the sum of our recorded experience and made available for (almost) anyone to access.

On the surface, multimodal large language models seem like a Surrealist’s ideal tool. Indeed, Surrealist themes have yielded some of the most stunning A.I. art collaborations we’ve seen so far.

For example, Unsupervised is a visual installation by renowned A.I.-collaborative artist, Refik Anadol, in which an autonomous A.I. choreographs a swirling masses of millions of multi-colored data points to express pixelated abstractions of the underlying data. The project, which began in 2016, uses general adversarial networks (GANs) trained on data from digital archives and public sources to “unfold unrecognized layers of our external realities,” much like the early Surrealists sought to unfold the layers of our internal reality.

However, A.I. offers automatism at the cost of the purity of thought that Surrealists hold so dear. Imagine you wake up from a dream with an incredible idea for an original piece of art. You scramble to your computer, open up DALL-E and race to type before your consciousness can catch up. You hit enter, brimming with hope for your upcoming masterpiece, only to find that the output image is a far cry from the one in your mind.

GenAI is a Surrealist’s Catch-22 in that way. You can either risk the intrusion of self-doubt to think up the perfect prompt, or you can fire off a quick prompt and leave the rest to the A.I. model. The model, however, is not attached to your unconscious mind and can’t act on its behalf. The model can access its own kind of unconscious mind, informed by the sum of recorded human experience contained in its training data. The result, then, is no longer a product of your mind, it’s a collage of elements from different data processed by a machine.

In an editorial on A.I. and Surrealism, Writer and Editor Rob Horning says that the point of A.I. “is not to estrange us from the familiar channels of our thoughts in the classic Surrealist manner but to more efficiently conduct us through them. Algorithmic text completion intervenes in how we think, making us absent where we are expected to be present, at the moment we are ostensibly speaking.”

The Surreal Life

Horning says that the ubiquity of generative text in modern life has made us all into default Surrealists, passively creating through the automatic methods of finger swiping, double tapping, scrolling, typing, and all the other simple gestures we’ve devised to shorten the gap between intention and execution. Meanwhile, social media algorithms mine our subconscious actions to train the machine, putting us in alternating states of harmony and dissonance with one another, like we’re the pixels in Unsupervised.

With our collection of shortcuts, automations, and curations, Horning says that A.I. “assures us that we don’t need to be the speaking subject behind our words, just as Surrealism promised.”

On the other hand, A.I. is contributing to a historic revival of the Surrealist genre. Artists like Refik Anadol and institutions like the Dali Museum are bringing us new visions of classic works and new works in classic genres.

Over a hundred years, Surrealism has evolved and morphed through political upheavals, cultural revolutions, countless art trends, and transformative technologies. While A.I. offers a powerful new method for creating Surrealist imagery, it is not the Holy Grail of automatism and connection to the unconscious that Surrealists tried to find in other methods.

We’ll leave the predictions about Surrealism’s future to Dali, the artist who dreamed of living forever through his legacy and once said, “Art is long, and so am I.”