A.I. and the Future of Photography: The Ultimate Tool or the Weapon of its Mass Destruction?

In this blog post, Jason Schneider discusses the effects of A.I. on photography and the wave of changes that are coming to the industry.

Will A.I. Destroy Photography?

“What goes around comes around” is an expression often used to cloak ignorance in the guise of worldly sophistication. But in its broad strokes, history does tend to repeat itself even though the specifics inevitably evolve over time. Such is surely the case with A.I., a subject that now has some of its leading creators and exponents, their hair on fire, issuing dire warnings that A.I. writ large will spell the doom of civilization, or even the human species, within the span of 2 years, 5 years—or, at most, 10 years!

Granted, the use of ever more capable A.I. systems to vastly enhance the surveillance capabilities of authoritarian regimes, the development and deployment of A.I. designed and enhanced nuclear, biological, and space weapons systems by malign actors, and the creation of seamless and credible disinformation campaigns by political extremists are frightening prospects. But what about photography? Will the exponentially expanding use of A.I., not only in cameras, but also as an integral part of the creative process, spell the end of imaging as we know it? Will it drag us kicking and screaming into a brave new world where the authenticity and veracity of a photographic image are no longer relevant?

Is Photography Art?

Is photography an art? The 19th century debate still matters in the 21st.

Photography, literally drawing with light, was invented in the early part of the 19th century. Nicéphore Niépce created the oldest surviving photograph of a real-world scene, a heliograph entitled View from the Window at Le Gras, in 1826 or 1827. Then in 1839 his friend and associate Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre perfected the Daguerreotype, the first successful photographic process to achieve worldwide distribution. By the mid -19th century, photo studios had sprung up in major cities all over the world, including London, Paris, and New York, and by the 1860s most towns of any size had a photo studio or an itinerant photographer that, for a fee, would immortalize you and your family with a Daguerreotype sealed in a gutta percha frame, a tintype, a carte de visite, or a framed print made from a sensitized glass plate negative. Some hailed photography as “the democratization of art” because it enabled common folk to have their pictures taken (and eventually to take their own) at reasonable cost, but many artists, academics, and critics emphatically disagreed. They argued that there are fundamental conceptual and operational differences between the processes used to create traditional art forms like paintings, drawings, and sculptures, and those used to create photographs. Ergo, while a photograph may be beautiful, engaging, and meaningful it can never meet all the criteria required to enter the exalted pantheon of true art.

Here are some reasons offered as proof that photography is not an art:

- A photograph is simply a mechanical reproduction of whatever the camera is pointing at, so photography is a mechanism for replication that lacks the refined emotions and sentiment that animate the productions of true artists. Therefore, it can never rank higher than, say, engraving or any other purely mechanical craft used to create or reproduce an image.

- Photography is a purely physical process that uses the “pencil of nature,” light itself focused through a lens onto a light-sensitive plate or film, to produce a geometrically correct rendering of a 3-dimensional object or scene on a 2-dimensional surface, a print or positive image. Taking a picture with a camera therefore does not require any specialized knowledge or artistic talent—anyone can do it by just “pressing the button” as it says in the 1889 Kodak ad.

- A photograph can be printed an infinite number of times, substantially reducing the value of any individual print. Even Daguerreotypes, which are unique images, can easily be copied by other photographic means and reproduced ad infinitum. This capability lowers the value of any photographic print, just as it lowers the value of so-called limited-edition lithographs of “art posters,” which are always worth less than comparable original works. If a photographer were to offer limited edition “art prints” of a specific photograph, one can never be certain that the original negative was destroyed, raising the possibility that some future edition will emerge, indistinguishable from the first, that renders your cherished print virtually worthless.

- Photographers are implicitly bound to physical reality, limiting their possibilities for invention, creative exploration, and imaginative flights of fancy that are afforded the true artist who starts with a blank canvas. It is, of course, possible to artificially add such elements to a photograph, but the result is a bastardized creation, lacking either the stark authenticity of a photograph or the heightened expressiveness and emotion of a true work of art.

Selectivity: the essence of artistic creation then and now.

To cut to the chase, the 19th century “photography isn’t art” argument can be summed up as follows: Unlike creating a painted portrait of Aunt Martha, which starts out with a blank canvas and requires countless brush strokes and considerable skill on the part of the artist, taking her photograph entails no input other than pointing the camera in the right direction, focusing on her face, and pressing the shutter release or, in photography’s earliest days, removing and replacing the lens cap!

Why Photography Is an Art: Arguments that Resonate in the Age of A.I.

Virtually all the bold 19th century assertions that photography is something less than an art rely on the unfounded assumption that it is the intensity and pervasiveness of the artist’s interaction with the medium that define its status as a work of art created by an artist. The rebuttal to this argument has a direct bearing on the use of A.I. in photography today: whether and when it is a legitimate tool, whether A.I. generated images qualify as artworks created by artists, and whether the results can ever be considered photographs, defined broadly as images created by the action of light on a light sensitive surface—digital image sensors, or chemically based film or paper.

Debunking the labor theory of value in its modern form

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries both the flinty eyed capitalist Adam Smith and the radical communist Karl Marx, embraced the concept known as the labor theory of value, which broadly states that the value of an object, such as a workman’s tool is, materials costs aside, roughly proportional to the labor required to create it. While this mechanistic idea may apply in certain specific cases, generally it’s poppycock, as anyone who’s bought an Armani suit, or a Gucci bag knows only too well. The analogous 19th century idea that photography isn’t an art because it’s too quick and easy deserves a similar fate. And the reasoning that refutes it has direct implications for the current brouhaha over the use of AI in photography.

As it turns out, the number of individual decision points entailed in creating a photograph or any other work of art is irrelevant so long as the artist’s intention can be articulated and shaped in a way that expresses the artist’s consciousness. In other words, intentional acts of selectivity can accomplish essentially the same thing as the sculptor’s chisel or the painter’s brush. Indeed, the miracle of photography is that by first selecting the subject, and then controlling two essential and irreducible elements, composition (what is in the frame), and timing (what instant is recorded), true photographic works of art can be created.

There are inevitably additional operational decision points embedded in each of these fundamental variables—the focal length of lens, its coverage angle, aperture, and imaging characteristics, the capture medium itself, the shutter speed, even the type of camera used. All these, and a slew of additional factors, determine exactly what the photograph will look like. Nevertheless, by controlling the two basic elements of space and time (selecting the subject, composing the picture, and determining precisely which moment is recorded) photographers can indeed express their personal vision of the subject, the world in which it exists, and the emotional character of that interrelationship to others—the very definition of art. The fact that a photograph is a more-or-less permanent image that can be transmitted to others across space and time and elicit emotional and thoughtful responses in viewers suggests that the art of photography is a form of visual communication—in the same category as painting, sculpture, and the other plastic arts that produce a physical “object of contemplation.”

Limiting Cases: Thought Experiments that Help to Frame the A.I. Dilemma

Imagine that a camera buff buys an old folding camera at a flea market for a couple of bucks and discovers to her astonishment that it contains an old roll of exposed Kodak Verichrome Pan 620 film that’s 50 years past its expiration date. What if she then develops the film and finds that it yields printable negatives, including one of a charming Norman Rockwell style 1950s farm family posing on their porch with the family dogs. If she now makes an 11×14 enlargement of the image after cropping out some distracting elements on the sides, would it be her image even though she didn’t take the picture? Could she publish it under her own name or enter it in a photo contest? Yes, yes, and yes. The fact that she rescued the image, perceived that it had value, selected it from other images on the roll, cropped it to improve its composition, made an enlargement, and then presented it to the world are all consequential acts that enabled the image to be exhibited in its present form. She didn’t load and set the camera, compose the picture, or press the shutter release, but her subsequent decisions “created” and shaped the image and made it possible for others to view it. She would certainly have the right to publish the picture and claim legal ownership, but whether she could enter in a contest as her own work depends on the rules of the contest. Could she possibly be sued by the descendants of the farm family for using their image without permission? In this litigious society anyone can sue anybody for anything, but I doubt they’d get very far.

Imagine a security camera, mounted in a ceiling corner pointing downward, and positioned to record events occurring at an ATM in a bank lobby. As with most such installations, the camera is programmed to take a picture every few seconds. Now suppose the bank was robbed and I went through all the recorded images to see if I could find a clear picture of the perpetrator, but instead I run across a picture of an angry man ripping a twenty-dollar bill to pieces and throwing it into the air like confetti. Would that humorously ironic image be considered art even though it was randomly captured by an automated system, and could I truthfully submit it to an art photography contest as my work?

Well, there were several decisions that had to be made before the image could be recorded—the exact position of the security camera, the coverage angle of the lens, the type and resolution of the recording medium, etc. If I installed the camera myself I would, in effect, be the one who “framed” the shot even if there were random elements in its timing and composition. But the main reason I could rightly claim artistic ownership of the picture is that I selected it from literally thousands of frames, valued its significance as a visual statement, and presented it as an artwork. Even if a security company installed the camera, the acts of selecting the picture and exhibiting it as something worthy of attention by other humans places it in the realm of art.

What about an image produced by A.I.? Can it ever be considered art, a creative work guided by the human consciousness of an “artist?” It depends. So long as its creation involves some level of human agency—configuring a verbal prompt or setting parameters, selecting which of several images the system delivers is to be presented, applying tweaks to the initial image, or reprogramming based on revised criteria until the desired result is obtained—a work created by AI can indeed be a work of art attributable to an individual or group.

Generally, unless an AI system such as face, eye or human body detection, auto tracking, background simulation, subject identification, etc. is built into the camera and enabled, one must input a set of instructions or suggestions for AI to take it to the next level and create and output unique images, and therein lies the human element. And even though the process may entail some randomness it is ultimately a human being that decides which images are worthy of being printed, published, or shown. Even if there were a hypothetical “AI machine” that just spit out images willy-nilly and automatically posted them on the internet, human beings would ultimately decide which of them were relevant and worthy of exhibition, and these “chosen images” would, in the broadest sense, qualify as works of art.

Transcending the boundaries of time and space, a work of art can convey essential elements of the artist’s life experience and creative vision to other humans, enriching their lives and enhancing their perceptions.

When J.S. Bach was asked why he wrote music, he replied succinctly, “For the greater glory of God and the recreation of the human mind.” While the great composer was undoubtedly pleased that people enjoyed his music, he also hoped they would find it uplifting, as the original meanings of the word “recreate” suggest; “to refresh, restore, revive, create anew, or invigorate.”

How A.I. Is Changing the Imaging World, Plus a Fun A.I. Experiment

A.I. is the process of machine learning, the simulation of human intelligence by a computer, so an A.I. system is differentiated from other automated systems used in the imaging field, such as autoexposure, autoflash, or even auto mode selection, and basic subject tracking, by its ability to retain information and to use that information to constantly improve its performance. In theory, you could configure an A.I. system to take “perfect pictures,” making the photographer an extinct species and photography itself a historic relic. But “perfect pictures” is a concept that would require an infinite database, not to mention that defining what a perfect picture is is inherently subjective and tastes change over time. In essence all A.I. can do is to help us to do more things more efficiently but at its most advanced stages it bumps up against the traditional concept of what it means to take a picture.

In case you haven’t noticed, there’s already a lot of A.I. built into your late model smartphone to let you create an array of backgrounds and special effects, simulate the beautiful bokeh effects of shooting faces with a medium tele at wide apertures, up the gain to increase the effective ISO in low light, automatically correct the color balance, and present the result on the LCD or in the EVF so you can see and compose subjects in virtual darkness. Many other high-end mirrorless cameras can do all that and more, such as providing enhanced dynamic range (HDR) images and enhancing depth of field and image quality by combining a series of multiple images of the subject captured at slightly different settings and combining them or selecting the best one.

Many of today’s high-end digital cameras have some A.I. features built in, but the current class leader in the A.I. sweepstakes is the new Sony ZV-E1 ($2,198.00, body only). It has a built-in A.I. Processing Unit that provides dynamic active mode stabilization using its A.I. recognition and tracking system, creates auto-cropping to focus in on a subject and the framing location, and is fully user-customizable. The camera’s bokeh switch provides custom adjustment for the level of bokeh. The Multiple Face Recognition setting allows the camera to automatically track multiple subjects within the frame and facilitates framing stabilization, which automatically tracks the subject within the frame to make sure the subject stays within the framed area. Finally, the ZV-E1 provides a Product Showcase Setting with an AF tracking switch that lets you maintain the same bokeh on a series of different subjects, including g those you’ve previously shot! We expect that digital cameras, particularly high-end models, will feature more, and more sophisticated options going forward.

When A.I. Goes Over the Top: The Samsung Galaxy Moon Kerfuffle

Samsung says that the cameras in its popular Galaxy series of Android smartphones “have harnessed artificial intelligence technologies to help users capture every epic moment anytime, anywhere.” As part of this bold concept, Samsung developed the Scene Optimizer that, starting with the Galaxy S21 series, uses “advanced A.I.” to recognize images of the moon and applies the feature’s detail enhancement engine to the shot. Samsung goes on to say that their system uses “deep learning-based A.I. technology, as well as multi-frame processing in multiple steps to further enhance details, harnesses Super Resolution to synthesize more than 10 images taken at 25x zoom or higher and applies noise reduction to enhance clarity and detail.” In other words, Samsung strongly implies that its Scene Optimizer starts out with the moon image you shot and extracts additional detail using advanced A.I. techniques rather than using generative A.I. or a database of comparable moon images shot at the same phase, angle, etc. to fill in any missing information.

Granted, exactly how Samsung did it might be inconsequential to many Samsung Galaxy users who would be delighted to capture sharper, more detailed moon images and show them off to their friends. Also, it’s clear that Samsung had no malign intent, but was merely trying to enhance Galaxy users’ experience. However, to quote a fascinating and well-written March 2023 piece by James Vincent and Jon Porter, “a recent Reddit post showed in stark terms just how much computational processing the company is doing, and, given the evidence supplied….we should just go ahead and say it: Samsung’s pictures of the moon are fake.”

While the very concept of “fake” has become increasingly hard to pin down, and it will inevitably evolve as A.I. is integrated into the photographic process, deliberate deception is still a no-no. In other words, so long as you say what you’re doing to enhance an image it’s probably OK, but fibbing about it is off the table. To determine whether Samsung was telling the whole truth about its “Galaxy moons” Reddit user u/ibreakphotos devised a disarmingly simple experiment—he created an intentionally blurry photo of the moon, displayed it on a computer screen, and photographed the image with a Samsung S23 Ultra smartphone. Initially, the image on the phone’s screen showed no detail at all, but the resulting picture showed what appeared to be a crisp, clear, detailed “photograph” of the moon. In other words, the S23 Ultra added details that couldn’t possibly have been extracted from the original image—no upscaling of blurry pixels or retrieval of seemingly lost data—just a new moon—a fake one! In other words, the system may first try to employ A.I. enhancement techniques, but when it can’t it creates something that’s more of a generated image than a photo.

While Samsung defends its enhanced moon imagery and continues to insist that it’s based on advanced AI enhancement techniques applied to actual moon images and does not include information generated from other data sets, it’s clear that drawing such distinctions is going to become more challenging going forward. As the article aptly concludes:

“Ever since smartphone manufacturers started using computational techniques to overcome the limits of smartphones’ small camera sensors, the mix of “optically captured” and “software-generated” data in their output has been shifting. We’re certainly heading to a future where techniques like Samsung’s “detail improvement engine” will become more common and applied more widely. You could train “detail improvement engines” on all sorts of data, like the faces of your family and friends to make sure you never take a bad photo of them, or on famous landmarks to improve your holiday snaps. In time, we’ll probably forget we ever called such images fake.”

Who Needs Photographers? Will Generative A.I. Make Us All Obsolete?

While scrolling through a provocative, surprisingly comprehensive online article by Nick Constant entitled A.I. Photography: How is A.I. Changing the World of Photography, I came upon an image that, as a native New Yorker I could immediately sink my teeth into. I can’t reproduce it here, but the caption reads: Image made with Midjourney (a generative A.I. system with a basic annual subscription starting at $96.00). I used this prompt: “A realistic photo of a New York sandwich with beef and lettuce on the tabletop of a hip restaurant shot on a Canon 5D with a telephoto lens and an f/1.4 aperture.” The resulting image was delicious–artisanal bread, the corner of a handmade table, limited depth of field, a warm color palette, all nicely composed. If I were a restauranteur looking for a promotional image for my high-end deli, I’d be delighted with it. If I were a professional food photographer who would have to spend hours in the studio to create such an image and then expect to charge $2k-$3k for it, I’d start looking for another job.

It’s important to understand precisely what this image is and isn’t—it’s not really a photograph at all, but a unique, computer-generated photo-realistic image created by accessing the computer’s database and using its algorithms to generate a new image that matches the verbal input prompt. It’s not an image selected from, say, the computer’s database of 3.5 billion images because then it might pluck out a copyrighted image shot by Joe Blow in 2006; it’s not a tweaked version of any individual image because that could still be subject to copyright violations, and it’s not technically a photograph because it wasn’t created by the action of light on a photosensitive surface such as a CMOS sensor or a frame or film. However, it’s assuredly the work of Nick Constant, the guy who programmed the A.I. system to deliver an image based his stated criteria, and he has every right to print it out, present and sell it as such.

How should the credit line read? I think Joseph Foley got it exactly right in captioning his gorgeous A.I.-generated picture of photographer with a tripod-mounted camera shooting in the glorious painted dessert of the Southwest (not shown here) that appears in his excellent online article, How A.I. Changed Photography Forever in 2022. It reads, “Image of a photographer in the desert produced with an AI image generator (Image credit: Joseph Foley using Stable Diffusion).”

Vintage Images in a Trice: The Fine Art of Generating Art Photos with A.I.

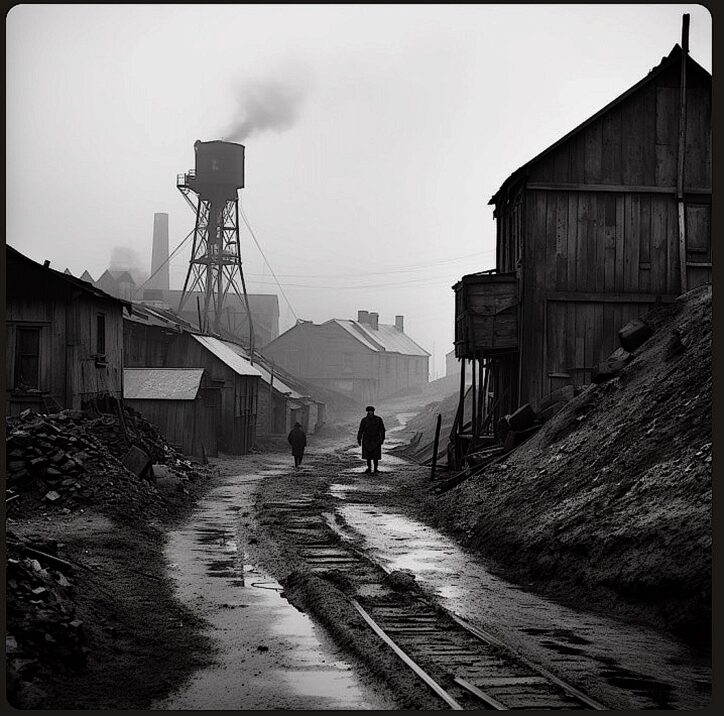

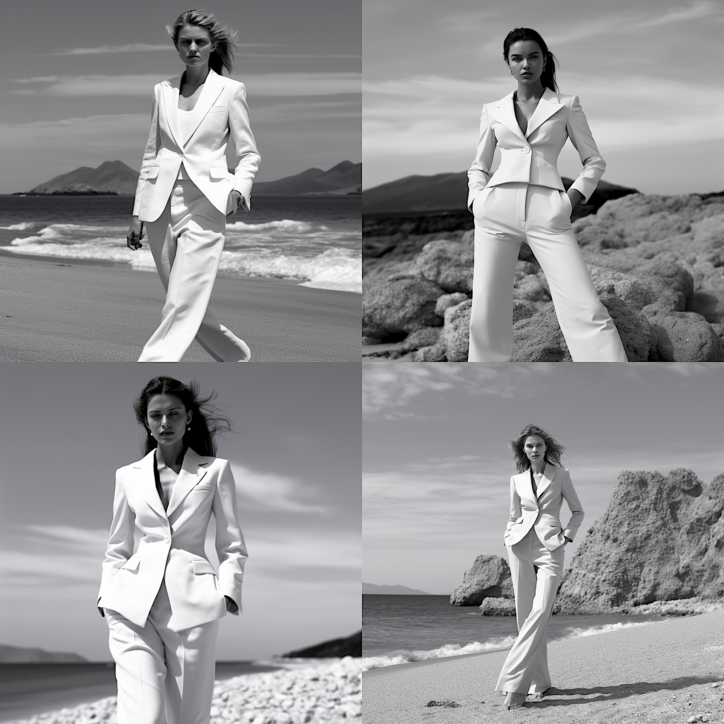

Just for fun, my multi-talented friend Lisa Ewart (who has Midjourney on her Mac) and I, decided to spend a happy afternoon creating A.I. images to see whether we could come up with anything compelling enough to print or publish. The results were, to put it mildly, astonishing, and much better than we expected. Perhaps the most amazing thing is that many of them were not only brilliantly executed in terms of content and composition, but that some of had an emotional depth that seemed to go far beyond the bare verbal criteria and into the realm of art. It was almost like standing the ancient dictum on its head—a few words are worth 1,000 pictures!

Our most productive prompt: “An art photo of a coal mining district in the classic photojournalistic style.” We tried this prompt several times and to see if the system would deliver different results. It did, although all were in the same ballpark as you can see. The best ones (shown throughout this article) are outstanding. On her own, Lisa submitted the following prompt: “A high fashion magazine cover of a model in Greece wearing an Armani pants suit on the beach in black and white photography.” The results are surprisingly good, if not quite up to what one would expect from a top Vogue photographer. Finally, the prompt. “A glamorous portrait of a young woman in the 1920s with black hair yielded 4 lovely images of nameless vintage beauties, one of which we selected for enlargement.

Whether you think A.I. is the greatest photographic tool ever invented, a technological time bomb destined to destroy the art and craft of photography as we know it, or something in between, it’s surely here to stay, and photography will never be the same. Just remember, many serious photographers wrung their hands and proclaimed that photography was doomed when a guy named George Eastman announced the Kodak, the world’s first point-and-shoot camera, way back in 1888. As it turned out, it made it a lot easier for more people to take lots more pictures, but it certainly didn’t destroy photography and I doubt A.I. will either.