Ep16. ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Part 2: Artists

Creativity Squared is proud to share the second part of a special series with our partner ArtsWave. The first series was released three weeks ago, (if you haven’t already checked it out, please do so: Ep13. ArtsWave Truth & Healing Part 1), and the final part will come out in another three weeks. These podcast episodes highlight the phenomenal artists and grant recipients selected for this year’s ArtsWave Black and Brown Artists Program!

Today’s podcast focuses on the vision of five artists for the world they want to live in and expressed through their art. You’ll hear about (each of these links to their accompanying blog post for each artist):

- “Lejanía” by Pablo Mejia, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Yemayá: Sista to the Distant, Yet Rising Star” by Camille Jones, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Attrition!” by Silas Tibbs, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Viewpoints Embodied: Middle Eastern Voices in Cincinnati” by Rowan Salem, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Legacy” by Alan Lawson, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Divided Roots, Seeing is Believing” by Preston B Charles III, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

They all talk about their individual projects and how it fits into this year’s theme: Truth & Healing.

Who Is ArtsWave?

ArtsWave is a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists. Because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue generated from Creativity Squared goes to ArtsWave to support their Black and Brown Artists Program. The mission of Creativity Squared is to envision a world where artists not only coexist with A.I., but thrive.

And in case you missed it (or want to revisit it), listen to episode 9 of Creativity Squared featuring Janice Liebenberg who is the Vice President of Equitable Arts Advancement at ArtsWave to hear her talk about how the arts can bring people together and for more on ArtsWave.

Truth & Healing Showcase

We had the honor of interviewing all of the artists at the opening of Truth & Healing Visual Art Exhibition, which is on display through September 10 at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center’s Skirball Gallery in Cincinnati, OH. It’s truly an inspiring, humbling, and grateful privilege to share their stories with you.

This year’s Showcase is focused on the themes of healing, rebirth, and reconnecting. Projects explore and build upon the current artistic commentary of health and race and connect it with historical events and visions of a more equitable future.

This year’s Black and Brown Artists Program cohort reflects a vibrant collection of diverse art forms created by an equally diverse group of 18 artists. Their mediums include couture fashion, painting, and sculpture — along with film, musical composition, podcasts, theater, dance, and multidisciplinary works.

The projects not only represent the African American experience, but also the experiences of those with Mexican, Lebanese, Somali, Argentinian, Zimbabwean, Guatemalan, and Indigenous heritage.

The intention of these interviews is to give these artists another platform to share their art and the truth expressed through it, as you never know what ripples will turn into waves.

Full Artist Video Interviews

Each podcast episode in this series will have accompanying videos with the full interviews with each artist. Watch them here or on our YouTube playlist. Each also links to an artist-dedicated blog post too.

“Lejanía” by Pablo Mejia

“When we’re able to express ourselves, and we listen to the stories of others, we can heal.”

Pablo Mejia

Meet Pablo Mejia, whose work walks the realities of arrival, with the beauty of new lands and possibility, contrasted with the pain we carried after that point. Pablo’s vision has been compounded by the strength and sacrifice inherent in immigration.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Pablo.

“Yemayá: Sista to the Distant, Yet Rising Star” by Camille Jones

“I’m reclaiming my right to live how I want to live and to live fully.”

Camille Jones

Meet Camille Jones, dancer with (CA)^2 (pronounced see-ay-squared), a creative street dance troupe founded by black women driven to uplift latent passion in all people through dance.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Camille.

“Attrition” by Silas Tibbs

“One of my goals with art and with cinema is to create those opportunities for one person to look at another person and just live in their universe for a while, and that might change your perspective and how you approach things.”

Silas Tibbs

Meet Silas Tibbs, a formally trained filmmaker, writer and thespian who seeks to use the mesmerizing powers of the cinematic, theatrical and visual arts to articulate the unutterable and deepest longings of every human. His work, though crossing many mediums, forms and genres, seeks to remain deeply human.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Silas.

“Viewpoints Embodied: Middle Eastern Voices in Cincinnati” by Rowan Salem

“Movement can teach us new things that we don’t already know.”

Rowan Salem

Meet Rowan Salem, a dance artist and educator whose work incorporates compositional improvisation, exploring perspective shifts through choreography and performance, all through her embodied experience as an LGBTQ person.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Rowan.

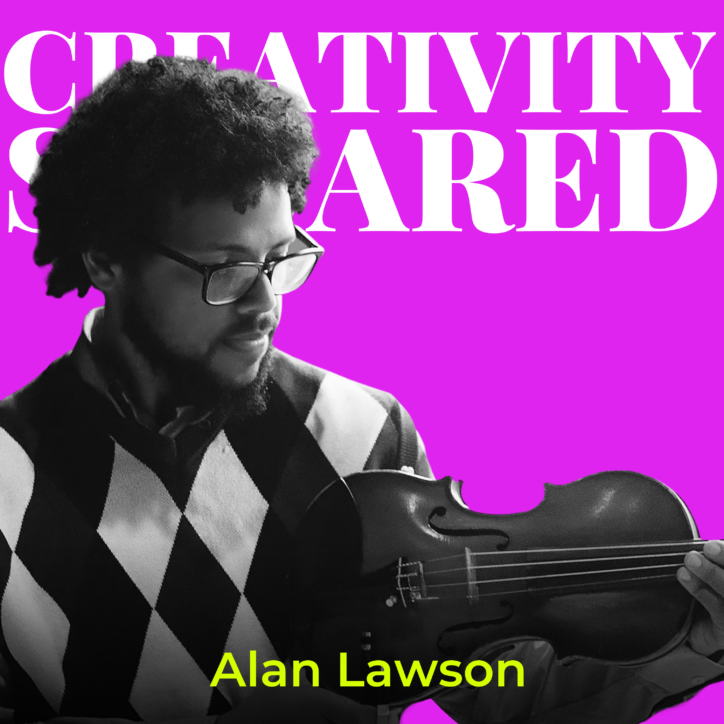

“Legacy” by Alan Lawson

“With music, you can bridge everyone together.”

Alan Lawson

Meet Alan Lawson, a musician and composer whose love of music has also led him to perform in prestigious venues such as Carnegie Hall, the Lincoln Center, the White House and Cincinnati’s own Music Hall.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Alan.

“Divided Roots, Seeing is Believing” by Preston B Charles III

“We’re from different races, we’re from different parts of town. But when it comes to music, all of that goes away, we can just let the notes take care of itself.”

Preston B Charles III

Meet Preston B Charles III, who brings the violin outside of the classical realm into a modern, immersive musical experience. This past year Preston helped create and score the documentary “A Citizens’ Journey Through Truth & Reconciliation,” a project powered by ArtsWave.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Preston.

Support Artists and Stay Tuned for More

If you’re interested in working with, featuring, or supporting these artists, please don’t be shy about it.

Links Mentioned in this Podcast

- “Lejanía” by Pablo Mejia, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Yemayá” by Camille Jones, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Attrition!” by Silas Tibbs, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Viewpoints Embodied…” by Rowan Salem, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Legacy” by Alan Lawson, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Divided Roots…” by Preston B Charles III, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- ArtsWave’s Website

- Follow ArtsWave on Instagram

- Truth & Healing Visual Art Exhibition

- Truth & Healing Film Festival

- Ep9. Janice Liebenberg: Art Bridges Cultural Divides

- Ep13. ArtsWave Truth & Healing Part 1

Continue the Conversation

Thank you to all of the artists for being our guest on Creativity Squared.

This show is produced and made possible by the team at PLAY Audio Agency: https://playaudioagency.com.

Creativity Squared is brought to you by Sociality Squared, a social media agency who understands the magic of bringing people together around what they value and love: https://socialitysquared.com.

Because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists.

Join Creativity Squared’s free weekly newsletter and become a premium supporter here.

TRANSCRIPT

Silas Tibbs: I think it’s very important that more and more people with diverse experiences are able to tell stories based off of their lived experiences. To create like that bridge, to create that empathy. Like it, it’s the truth part because again, another thing that I like about art and I like about cinema is the fact that art bridges the void between one person and another.

Like, I subscribe to the idea that we, we all live in our own pocket universe. Like, we could be standing next to each other. But our experiences are so personal, and how do we really know what the other person feels?

The concept of language to me is magic. The fact that I can like utter sounds and another person completely separate from me, understands what I’m trying to say, let alone articulating a feeling, let alone articulating an experience.

And so people with diverse experiences, having hold of a medium creates interconnectivity in a community.

Theme: But have you ever thought, what if this is all just a dream?

Helen Todd: Welcome to Creativity Squared. Discover how creatives are collaborating with artificial intelligence in your inbox, on YouTube, and on your preferred podcast platform.

Hi, I’m Helen Todd, your host, and I’m so excited to have you join the weekly conversations I’m having with amazing pioneers in this space.

The intention of these conversations is to ignite our collective imagination at the intersection of AI and creativity to envision a world where artists thrive.

Theme: …just a dream

Helen Todd: Today we have part two of a special three-part series that’s being released every three weeks, highlighting the phenomenal artists and grant recipients selected for this year’s ArtsWave Black and Brown Artist program. For the full video version of these conversations, visit creativitysquared.com or the Creativity Squared YouTube channel.

And if you haven’t already, sign up for our free weekly newsletter so you don’t miss any news at the intersection of artificial intelligence and creativity.

The mission of Creativity Squared is to envision a world where artists not only coexist with AI but thrive. In this episode, we’re focusing on the vision of six filmmakers for the world that they want to live in and expressed through their art.

Pablo Mejia: My name is Pablo Mejia

Camille Jones: My name’s Camille Jones.

Silas Tibbs: Hi, my name is Silas Tibbs.

Rowan Salem: My name is Rowan Salem.

Alan Lawson: Hi, my name is Alan Lawson.

Preston Bell Charles III: My name is Preston Bell Charles III.

Helen Todd: We’ll be hearing from these artists whose films were shown in the ArtsWave Truth and Healing Showcase and film festivals. Part one of the series features the artist whose work is in the exhibition that is available for visiting at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio through September 10th.

From episode nine on the show, Janice Liebenberg, who’s the Vice President of Equitable Arts Advancement at ArtsWave shares.

Janice Liebenberg: And for us, a blueprint for collective action includes that the arts bridge cultural divides, and that is, you know, so key for us as we invest in the arts and how we schedule our programming and how we just feel that the arts can bring people together. No matter what divides us outside of the arts, the arts can bring us together.

Helen Todd: Creativity Squared is a proud partner of ArtsWave and because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue Creativity Squared generates goes to ArtsWave, which is a nationally recognized nonprofit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists.

This year’s ArtsWave Black and Brown Artist program theme is Truth and Healing, and I had the great honor of getting to interview the artists during the opening showcase to learn more about their work and what truth and healing means to them.

I’m inspired, humbled, and grateful to share their stories with you. The intention of these interviews is to give these artists another platform to share their art and the truth expressed through it. As you never know what ripples will turn into waves. If you’re interested in working with, featuring or supporting these artists, please don’t be shy about it.

With that, here are six vignettes of our conversations. Enjoy.

Theme: Just a dream.

Pablo Mejía: My name is Pablo Mejia. I was born on the border, lived in Mexico for a few years, and then my family immigrated to Texas. I moved to Cincinnati about two years ago now. My partner has a job at Miami and I just moved here with her, so that’s kind of how I ended up here.

The title of my film is Lejanía. And I’ll give away like what it means, like Lejanía is like the remoteness or like the distance. For me the like, essentially this film comes out of just my own lived experiences, like coming to this country and then also moving to Cincinnati.

Felt like, you know, I, I have now distance from where I would call like home. And it also comes from seeing my mother like navigate being an immigrant and trying to adjust here in the United States and what that sort of looked like for her. But I took all those experiences, I found real people in our community and then I abstracted their stories and somewhat combined mine into like this film.

It’s like a mishmash of like narrative and also magical realism. And then there’s also like a documentary aspect to it. So there’s kind of a lot of things that I just kind of like threw together to see if it would work. ’cause it really is kind of an experiment. And I feel like right now where I’m at with my projects, I really do wanna like keep experimenting to discover sort of new forms that are on the fringes of filmmaking.

I want to first like big shout to my cinematographer Bryce. He is like one of my longest collaborators. And before, you know, we write the script and you know, we have the idea of what this story is. And from there we kind of take the approach of, okay, how do we want this film to look?

How do we want to portray our characters? And so that we kind of arrived on this look that is very real. Like we’re not doing a whole lot of crazy lighting stuff, but we are elevating our characters somewhat to be a little bit more like beautiful and pleasant. Because I feel like the culture that I come from is a very warm and is a very caring culture. So I wanted to show that and how we’re portrayed.

Being a grant recipient means that one, we were granted a crazy amount of freedom to make this project. Like obviously there’s a timeline and there’s time crunch to get it done, but they give us these ideas or themes that we’re making our projects about.

But other than that, they really do give us the freedom to make whatever we want. And that’s very liberating as an artist to really take in like your own ideas and to go out into the world and create them with, you know, funds from ArtsWave and like, that’s amazing. I think it is a career changing opportunity for a lot of people because like that kind of money, especially from where I’m from, like it’s just, you know, it’s hard to find, right?

And really it’s also very validating at the same time. Like, it’s like, wow, like, people care, but this organization caress, right? That’s like putting a spotlight on you. Like my project was on a billboard outside. And like that’s super cool. You know, like, so it’s very validating in that sense. Um, ’cause I know like myself as an artist, like I have a bunch of imposter syndrome, right?

Like am I really making these kinds of works? Like am I really a filmmaker? And having an organization like ArtsWave put that light on your project is like crazy good. So amazing. I think like freedom is one of the most universal human experiences that we all have and I think that search for freedom is inherently tied to all the projects that we’re making.

And I’m excited to see what people think of my character’s search for freedom in the film and to be able to present at the Freedom Center. you know, I think that is like amazing and like the symbology that this place represents. And then when I was making this project I was always thinking about the screening ’cause like it’s gonna screen at this place that means so much to the progress and like trying to push for more freedom to like all sorts of cultures and everyone around us.

So having that mind with the project, I was always thinking about like what is it gonna feel like when people see this at this museum that is dedicated, right, that is across the line of border, that is a part of American history. And borders are part of my narrative here. So I’m trying to juxtapose some of that and I’m excited to see what people think of the film as well.

I had, you know, this idea for this film in 2018. I visited Tijuana during the border crisis and I went and documented people that were at the border during that time. And from there I started to interview people and kind of get an understanding of this like kind of phenomenon that’s happening at our borders because like being a child that have been immigrant, like we experienced some of the things that people experience now, but it’s nothing like that now.

It’s completely different. It’s something that I don’t think the United States has ever seen. So it started then, but then when I saw this grant, I was like, okay, I can apply it to this. And Cincinnati has a very small Latin community. So I knew that I wanted to highlight those people.

And then it does follow people’s real lived experiences. I went out into the world once I was awarded the grant, I knew that I wanted to focus on this subject matter, and then I found the real people that fit the narrative that I was telling. But during the process of that, I recognized that there was another layer that was speaking to me through the course of me, like being out in the world and searching for people.

So when I started to listen to the stories that were being told to me, I then took those stories and applied them with my own film and created what we have now. And part of that is the journey of someone who is, you know, fleeing their country in search of freedom and just the weight of coming here. And then also having the opportunity to express themselves.

Because a lot of times I feel like when we’re able to express ourselves and we listen to the stories of others, I think we can heal. So I think my film is, is about that, and it’s also about how you find hope in the stories of others. My mom, when I was growing up here, sometimes we would be driving throughout the highways and we have these highways that were just going on top of each other and we would be driving.

And I remember my mom would’ve like be looking around and she would ask herself, like, who would’ve known that we would be like here? Right. So there’s a sense of like wonder because it’s like a new place, a new area, and there’s like that to it. So like, seeing my mom express that is directly in the film.

And I wanted to like show that sense of like, wow, like, you know, look at this new place, you know, like, look at this new area. I think people that are from here don’t appreciate it as much. And people that come into this world see this massive like infrastructure, you’re just kind of like, wow, holy shit, I’m here, you know? So it’s, yeah, there’s that too.

And I mean, if you’re not from the United States and you’re from Latin America, the United States has a brand image to it. So people like, come here with this idea what it is and they find out what it really is. So that’s kind of also what the film is about, but definitely trying to capture that like sense of like, awe when you walk into a new environment or a new place.

So choosing my protagonist really came down to finding someone that when I looked at them, I knew that I just wanted to hear their story. And when I met Jimena Enza for the first time, I just couldn’t help but think of my mom. And after that, it just became kind of easy to like think about how I would portray them.So it was really nice.

And then my partner Tina, helped me out a lot with like, some of the acting and talking to coordinating with everybody. We had a very small crew of people. We had like five people I think. So it was a very small crew. But again, like portraying a female character is like, it’s difficult because you’re trying to like find the right balance of like, how much of my own experiences do I put in?

And then it really came down to like listening, like really intently to what these people were telling me. And then like me as a director, just being like, okay, let’s put the camera here. I’m thinking about two people that are gonna watch this. There’s the people that have never really spoken to someone from Latin America, probably ’cause they don’t speak Spanish.

And then there’s people that do speak Spanish and they’re gonna see this. So when I think of the people that don’t speak Spanish, I think of like, or that have really never interacted with these people other than like a couple of things, right? I wanted them to sit down and to like be in an intimate space with my characters.

And that to me was really important because like, that’s what film offers us, is that experience to be able to sit down and like, listen, hear, experience different cultures, different people in a very like high definition sound and like video, right? So I wanted people to feel like they were in the room and, and like putting that like, focus on someone’s eyes, you know?

I feel like it just, it makes me feel for them. I think it’s just me manipulating people to be like, look at this person super close, you know?

My mom cleans houses for people and, and they would always ask her like, why are people coming to this country? That’s kind of what the film is about. In a nutshell, my own truth that is being expressed through this film is feeling like I am at a distance from the rest of the culture that is around me and I’m trying to fit in. I’m trying to be a part of the majority, right?

But there is something that is keeping me at the distance, you know? Yeah. I think some of that is my culture, where I come from, and then like seeing, you know, seeing the city in the backdrop, like saying like, do I belong here? I think that’s where my truth comes in with this film.

Emotionally as an artist, I think like I have a hard time expressing myself to regular day everyday people. So I do use my work as a means to do that. And I think, again, like I just have a compassion, right? Like these kinds of projects, like they open up your mind to what people are experiencing that you would not know otherwise.

I think I’m just much more like open and, you know, to listening to people and, and like, you just never know what people are going through. So I think this project has really opened me up to really listen to people. Life is beautiful. I think the characters that I portrayed in this film have gone through hard times and hard things have happened to them in their search for freedom, but even then, like they have this view of the world that is very beautiful.

And I think like if we all kind of take some of that away, I think then the film did it justice.

Theme: Just, just a dream.

Camille Jones: My name’s Camille Jones. I’m born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio. I’m a multidisciplinary artist here in Cincinnati. I dance, I write and I’m a collaborative person, so I collaborate on a lot of different projects with different artists here in the city. And I am a co- collaborator on the Yemaya: Sista to the Distant, Yet Rising Star project.

It’s a collaborative project between myself and my dance team CA Squared, which is made up of my sister Chenelle, my dance chosen sister Anaya Ni’Kole, and then of course myself, Camille Jones. And then our collaborators Warmth Culture, which is made up of CJ Wooten and Alex Stallings.

And together, we worked with other artists, so we extended our tree to include other artists.

So that meant DJs like DJ Queen Celine and DJ Rod D and Visual Artists. So Monsta Audio and Visual Team, Pixel Designs and DJ Pillow. We all came together to bring forth this sort of reimagining of a piece that was originally presented at Blink in October 2022. And they just had an idea to sort of activate audiences.

So of course they wanted music because they deal primarily with bringing DJs to the forefront and creating like musical landscapes with DJs. But they reached out to CA Squared because they wanted to add an extra element to that activation at Blink and they wanted dance. So they reached out to us.

And Alex of Warmth throughout this title, like a working title for called Yemaya, which was inspired by a film called Love Jones. And in that film, there’s a scene where Larenz Tate’s character like recites a poem. And in that poem he says, like, Yemaya: Sista to the Distant. So I took that title and kind of like ran with it. And I created some original poems for the piece. And CA Squared choreographed three different phases for the activation.

And with the help of the DJs, we created this like, really cool presentation, like this body of work. So we had like DJs performing sets, and then the dancers, we presented our choreography. That also coincided with the poems that I wrote. But then the following year or this year, there was an opportunity to apply for the ArtsWave Black and Brown Artist grant that CJ sort of like threw out there to the group.

And then it kinda just went from there. We decided we were gonna go for it. So, CJ and I wrote and submitted the grant. And yeah, we thankfully got the grant, which is really, really cool. We were not expecting that really. And then we were able to bring more life into this original idea. We curated two events, so we curated a brunch for Women’s History Month, and then we presented the actual performance art project in May at 21C Museum Hotel.

And so that one was primarily basically bringing that little show that happened at Blink, that activation at Blink, and just bringing it into a more intimate environment and extending those phases out in creating a more fleshed out storyline. So the film is a part of the grant, but for like the longest time, I’ve wanted to just create a documentary essentially of like just a process of a project.

And that’s something I just talked about with my dance team a lot. So I sort of like pitched it to everyone, so Warmth and CA Squared, throughout this like grant process. And they were completely on board and we already had Monsta who was in charge of basically documenting the Blink performance. So Monsta was already on board to film and capture for the ArtsWave grant project.

So essentially what we just decided to do was show everything from the very inception. So show those steps, like the beginning stages from Blink, and then bring it all the way to this point where we actually presented the final piece, the final fully fleshed out piece at the 21C performance. So yeah, that the documentary was something that kind of was always in my mind, always like a dream to me to be able to do.

And I think it helps too. It adds to like the story of seeing women sing. Female presenting figures in leadership roles, women of color, non-binary people stepping up into these like huge roles and reclaiming what belongs to them. Like taking up space and being explosive with their voices, with their bodies, with their ideas.

And I think that’s what the documentary did like successfully. Like I was really blown away by it. I think it turned out better than I even like imagined it. So I’m really proud of it. I’m super grateful to Monsta and Monsta’s team for doing that for us.

And honestly it was a huge deal for both me and Chenelle because for the longest time we just talk about all these aspirations that we have and we’ve always been like that even since we were kids.

We would just like dream together and just like talk about our ideas. So for this to happen, for us to, to receive like this grant and to be able to work with people that we really care about and that we believe in, and that we are inspired by, that meant so much. That meant that first, that we were affirmed, that somebody saw whatever idea that we had and said, okay, this is something that needs to come to life.

It also confirmed that we do possess all the tools that we need to accomplish our goals. So we don’t need to look outside of ourselves too much for whatever it is we think, you know, will help us get to wherever we need to go. Cause I think oftentimes we think, oh, I’m not brave enough, or I’m not creative enough, or whatever it is that you think you’re lacking, you’re really not lacking at all.

And this was a testament of that, of that truth really because that grant was submitted again, like we didn’t think too much of it. We were just like, just try. I’m always, I’m a big person on just trying things like even if you’re like, oh, I’m just gonna fail, at least try. So we tried, we let it go, we put it out there and then for us to get the news that we received the grant was just like, okay, maybe we are enough.

You know, maybe we can do this thing. So yeah, it was really affirming and just again, sealed something in our hearts that we do possess all those qualities to achieve greatness. As I wrote the poetry for our project, I just thought a lot about Yemaya as this figure, especially in like African folklore, mythology, Yemaya represents life.

And when I read about all these things and I’m thinking about life and where life comes from, and at the time my sister was also pregnant, I think we got the grant right before she actually gave birth. So we, there was just so many things, like life was literally changing for my entire family. And I was sort of, I was so inspired by her, like throughout her process, her entire pregnancy, I was so inspired by the woman that she was evolving into and she completely represented all like that figure that I was studying at the same time.

And it wasn’t an easy process for her, I mean, it’s, you know, that’s huge. That’s a life changing experience. And I sort of leaned into that. Like, what does that look like when a person, when a woman is, their body’s changing in an entirely new way, and not even just their body, but their mind too. And you’re sort of preparing yourself for like, for a new life and what does that mean to you, and then how does that change how you see yourself in the world?

Because again, I talked about how we, we spend so much time sort of like talking ourselves out of things, or we feel like we, we just don’t. Have enough to achieve something. But I think I was just like witnessing this evolution in my sister where she was like, whatever I think about myself, even if I thought I’ve like lacked something in the past that no longer matters now because I have to just get ready for this new being that’s stepping into the world who needs me.

And yeah, that was just profound for me to witness. And I started to read more about how Yemaya, the storytelling of Yemaya is used to sort of be representative of the plight of black women and black femininity and like what it just means for people to be black and feel that their blackness isn’t under attack, to be a black woman and feel like you’re being a black, being black and a woman aren’t like two opposing things or like or two problems at the same time.

So yeah, so this piece allowed us to explore all those things like this, this really complicated, you know, bowl of just, ideas and concepts and constructs and stereotypes and sort of just kind of decide, we wanna throw those all away and just decide how we wanna present ourselves and what our story looks and sounds like.

The word of like reclamation, which was used so many times in the piece, especially if you watch the documentary, you hear that word a lot, like reclaiming time, reclaiming your body, we really wanted to lean into that. Like, I’m deciding as a woman, as a Black woman, as whatever society’s decided to call, like other, I’m deciding that that no longer serves me. Whatever I feel like I’m lacking or whatever I feel doesn’t match up with what other people think is right. I don’t care about that anymore because I’m reclaiming my right to live how I want to live and to live fully.

So healing came even in the process of creating this entire project. And I hope that people can see the healing in each of the dance pieces and see the point of the healing in each of those phases. Cause phase one, you see like the vulnerability, phase two, you see those moments of having to fight and the resistance against what society tells you is right and how you’re wrong, you just show up wrong, you’re born wrong.

And then phase three deciding, you know what? I don’t care about any of that because I, I’m choosing to accept who I am and I’m choosing to live how I wanna live and present myself to the world. I think a truth that is expressed in the Yemaya project that I like personally relate to is just to, step out with boldness and, and embrace who you are. Yeah. And be like fully embrace that. You don’t have to apologize for who you are.

I have a tendency to always say sorry. And that there’s nothing wrong with that either. I think it’s a good thing to be able to apologize quickly and to have empathy and compassion. But I do sometimes apologize to like, I don’t know, maybe to shrink myself or to sort of be like overly accommodating.

And I’ve learned to sort of find new ways to work around that, especially when I’m like apologizing for something that isn’t even my fault. But yeah, I’ve been learning how to just sort of be like, Camille, it’s okay to be you. It’s okay to be bold. It is okay to not always just be like, you know, the pleaser, you know, or to be super liked or anything like that. So just step in with your boldness and embrace that and be comfortable in that. And that’s all I can control.

If there’s one thing to remember, I want viewers to remember to just reclaim their right to live fully human existences.

Theme: Just, just a dream.

Silas Tibbs: Hi, my name is Silas Tibbs and I’m a Cincinnati filmmaker. The genre of this film is a dystopian sci-fi. It’s very Orwellian in nature. The name of the film is Attrition, and that comes from this idea of like a paring away over time, like an erosion over time. The inspiration of this film came from a very unsettling conversation that I had with a college roommate.

I went to college in Oklahoma, and this was during like the height of the Tea Party movement and also around the time that Obama was elected. So being an African-American in the heart of a like solid red state was a very interesting experience, and I faced a lot of perspectives that were more overt than I was used to.

And my roommate at the time, just to put it frankly, there was a lot of fervor about immigration and there was a lot of anti-immigration, and it was a problem that had to be solved. And so my roommate started talking about his concerns about immigration and this is kind of spoiler a little bit, so hopefully you’ve seen the film first.

But his solution was, well, let’s limit the amount of children that immigrants can have. And it was one of those moments where I was either gonna get mad or help him follow his thought all the way to the end. And so we just kind of had a conversation about, okay, if we did that, what kind of country would we turn into?

And the thing that was a little bit unsettling to me about that conversation was the fact that like we both had our degrees at that time and he had moved on to like his master’s. And so we’re both two educated men that are gonna go off into the world and like start to navigate where our country goes.

And that thought was something that occurred to him without any problems or issues. Now, fast forward down the line and we see more people like this that are in office and what started as like a thought experiment is starting to feel more realistic. And so the inspiration of this film comes from two places.

It comes from that story, but then it also comes from maybe well-intended consequence of a racist system which can operate without anyone really acknowledging that it’s there and it’s an erosion process. So fighting hard to reach equality in a system. There are people that reach that equality, but how many don’t?

And the higher you go, the fewer and fewer people you find people of color that are in place of power, that have influence, that can actually like control or help guide where the money goes. So then the higher you go, like there’s just not very much representation.

And there are systems in place that have this kind of erosive effects not only on just getting places, but also emotionally and physically. There’s a lot of like working harder to get to a place of equality. A lot of people physically don’t make that journey to the end.

So there’s a lot of like hints in there. But a lot of it comes from like conversations I’ve had, but then also experiences that I’ve had, other people’s experiences, watching my parents like fight to get us to a different place.

Like my parents, they were the first in their family to go to college and their fights to get into college was hell. And then, so then we were second generation to get into college and our fight to get into college was also hell. And there are a lot of people who see that fight and they’re like, why? Why would I do that?

Especially if it’s too expensive and if like, we graduate college, but we don’t actually still make the same amount of money, what’s the point of that? And that all is attrition where it makes it harder and harder. To progress and it makes the fight to wanna progress, feel a little bit hopeless.

So I think that that’s like a perspective that’s well missed in this discussion of equity and inclusion and diversity and these kind of places where you look and you’re like, well, the opportunities exist, but why are so few people of color in these spaces? Well, the fight to get there is hard and a lot of people don’t see the worth of it, and some people don’t make the journey.

I was very grateful to be a recipient of this grant because when I pitched this story like this, the story, it could be controversial. And so I appreciate that ArtsWave saw the concept and believed it was something that was worth funding. So I’m very appreciative to have the opportunity to be able to tell this story because of the grant. This year’s grant is Truth and Healing.

And one thing that I believe like very deeply is that we can’t skip to healing without truth. And one of the biggest issues that I have with the national dialogue, especially in some places, is the need to want to like soften truth and then kind of like quietly slide to healing.

But the magnitude of the trauma that’s been done to black and brown people, and not just African Americans, but black and brown people just in general in America, I don’t think is very well articulated, specifically generationally. And so for this project, and it’s as an aspect of my personality just in general, I like to be very, very straightforward.

So for me, the conversation starting with truth is the thing that leads to a way to heal intelligently because I don’t like the concept of pretending that we’ve healed, but we’ve skipped a lot of steps and we’ve skipped a lot of things that need to be resolved. It’s like we close up the wound before the surgery is even fully done.

So for this project, it’s a heavy emphasis on truth and it’s an appeal to vigilance, not just for African Americans, but for everyone who watches the film so that we can all start on a level basis, a very level basis.

I’ve fallen in love with film because the saying, a picture is worth a thousand words is so true. I wanted to be a writer before I wanted to be a filmmaker, and I just found myself writing infinite words essentially to express like feelings that are like very, very, very hard to articulate, but the art of capturing cinema uses pictures in ways that words can’t really access to trigger parts of our feelings, of our emotions, of our intellect and that kind of thing.

So there are images in the film that are very intentional and come from a place of experience where if you’re a person of color and you’re in government assistance, there’s the assumption that, well, you’re here because of either laziness or because of something you did wrong. And there’s like a lot a condescending attitude sometimes.

And this is not in all cases because there’s a lot of social workers that are very empathetic and that’s why they’re in the field. But then there’s also situations where it’s like, why am I going through this? All I want is food for my children, kinda a thing. Like very basic human needs. And we have a government and we go to them for assistance and it feels like we’re getting a runaround kind of a thing.

And so like images like that come from childhood memory and like there’s a thing in cinema about holding a memory that you have and finding all those details that we may not think of are important, but they create that texture that will trigger someone else’s memory or experience. So just being in that environment, like feeling like you’re being talked down to when you’re just seeking something that’s like basic, like sitting in a line for hours just to get food for your children.

Like these are experiences that a lot of people of color, a lot of people who don’t have access to money go through and it’s like a story that’s untold. And I mean, we can blame certain people for the idea of the welfare queen and how it’s just like laziness and like, but that is not the case at all.

Like it is a grueling, mentally exhausting, emotionally exhausting, humiliating experience to have to endure some of those things just for basic human rights or just to be able to eat or just to be able to like pay your electric bill or things like that. That’s why I open the way that I do with that animation.

Or even like the first shots, like I’m intentionally drawing attention to the person, to humanity, to bridge that gap, to like, I’m kind of playing with like all of our, the buttons in our brain that remind us we’re looking at a person. It’s not just a film, which is the first line that you have to cross with the audience is, okay, I need them to believe the world.

I need them to feel like that they’re in this spot. And then you want to bridge the gap between the audience and your protagonist. But there can be a barrier still sometimes with ethnicity where it’s like, okay, well I see him, but that’s not me. And then once you have them cinched, then you can carry them through the rest of the story.

And that is a very, very difficult thing to do. That’s why when you watch movies like Moonlight, like you’ll see with a lot of other like black directors who are above me and who I admire right now. Ava DuVernay for example, does this where there’s a fixation on the portrait of the face. Because we all know in the back of our mind, like that’s our first real hurdle as filmmakers of color in a society where we are the minority, we have to create that human connection unless the story just falls apart.

And it’s one thing that like, I mean, I grew up and like I’m a child of Star Trek and all of the captains up until one were white males, right? But when I was a child, I didn’t care because it was like, these are cool people that run starships, you know? And I wonder if that same thing happens on the other side.

If it were a black captain, would they go, well, this is not for us. So like that’s the first challenge that any black filmmaker has because we’re trying to get to the point where they connect with a protagonist. Now that they connect with their protagonists, they can hear the story that we’re trying to tell.

I think it’s very important that more and more people with diverse experiences are able to tell stories based off of their lived experiences to create like that bridge, to create that empathy. Like it, it’s the truth part because again, another thing that I like about art and I like about cinema is the fact that art bridges the void between one person and another.

Like I subscribe to the idea that we, we all live in our own pocket universe. Like we could be standing next to each other, but our experiences are so personal and how do we really know what the other person feels? The concept of language, to me is magic. The fact that I can like utter sounds and another person completely separate from me, understands what I’m trying to say, let alone articulating a feeling, let alone articulating an experience.

And so people with diverse experiences, having hold of a medium creates interconnectivity in a community. This is the one thing I want them to remember, and this is just generally, and this is like the goal of art for me, but look at another person and live in their universe. And that to me would solve a lot of problems if we approach with empathy and compassion.

And it’s one of my goals with art and with cinema, to remind people and to create those opportunities for one person to look at another person and just live in their universe for a while. And that might change your perspective and how you approach things. And if it doesn’t, you might need to look in the mirror.

Theme: It’s just, just a dream.

Rowan Salem: My name is Rowan Salem. I am originally from Massachusetts outside of Boston. I currently live in Cincinnati. I’m a modern dance choreographer, performer, and educator, and my project is Viewpoints Embodied. It’s a series of four dance films inspired by interviews with Cincinnati residents of Middle Eastern descent.

The four films in this series are a series of interviews with Cincinnati residents of Middle Eastern descent. I am a modern dance choreographer, and I sometimes work in dance film, but this was like kind of my deepest dive into dance film. I was curious about using stories like this and using it as the audio backdrop and then layering my movement on top of that, and so I found four people in the community with very different perspectives and backgrounds to share four different topics.

Leah introduces Islam as almost like an educational five minute lesson to anyone who is not familiar with Islam. I think there’s a lot of misconception about that religion in this country. A lot of post 9/11 Islamophobia. So I was really excited about that. I learned a lot just by talking with her.

We spoke for an hour and I had a hard time cutting it down. I just learned so much and I think it was a really beautiful topic to work with. And then Kate Zaidan owns Dean’s Mediterranean imports in Findlay Market. So Kate speaks about the principles behind Lebanese cuisine and just in a beautiful, eloquent way. She is very like practiced in this, it seems. So we danced in her shop in the aisles.

And then Noelle Maghathe is a Palestinian-American performance artist and visual artist. So I introduced their philosophy of why they work with that topic. And then we use one of the pieces, a candle in the shape of a fence representing borders in Palestine and just use that as our movement inspiration.

And the last film is Ian Quirky. He is a pediatric nephrology fellow at Cincinnati Children’s, and he just speaks about the differences in the medical system in the Middle East America ’cause he trained in both places and kind of the pros and cons of the fact that we have such amazing resources here. So four very different topics.

I did the interview first for everybody, and then I have a big postmodern dance influence, which really emphasizes the creative process. The idea is that you don’t go into the process already knowing what’s gonna happen. You kind of engage with the concept. And the dancers are very collaborative in postmodern work.

We all engage in this sort of question together or topic, and then the creative process teaches us. So I use a lot of compositional improvisation. I will give the dancers like a set of rules or a task like you have to get from here to there. And here are the rules.

Like you can roll down the wall, you can’t use your arms, or you are going to flock each other. So whoever’s in French, you’re gonna follow them. And then when you feel it’s right, change the flock to the person in back or something like that. And so, yes, the interview inspired the creative process. I do not do a ton of planning ahead of time. I try to do just enough.

In terms of film editing and dance film, I am kind of new to this world. This grant was an incredible opportunity for me to dive in and I realized I wanna learn a lot more. But I think the two films, Eyad and Leah, are a little more highly edited like post because the camera’s stationary in those, in those scenarios. And so I kind of use that like opportunity that I can like splice the scene or like fade them in and out.

And then in Kate, in the grocery store, the camera is moving and it’s a dancer itself. So like that, we did a lot of really long takes with that. So yeah, just like very different choices and styles. I guess this is like a huge identity dive for me. I am half Lebanese, Middle Eastern, but totally like identify as white and pass as white and enjoy all the privileges that that affords.

And then I did my 23 and me, and then I had a fateful conversation with somebody who works at ArtsWave and it just sort of like fell into place and I was like, wow, this is a really important part of my identity and part of my family’s story. My grandparents just wanted to live the American dream and did not teach me the language and did not honestly tell me much of the stories either.

So I’ve been talking to my dad and so I almost just see it as like sort of paying back a little bit for like my great grandparents and my grandparents’ hard work and a chance to amplify voices of a whole community here that I think people don’t think about. People think about Cincinnati is really black and white.

Process of finding these interviewees was very difficult for me because I am not entrenched in the community. I don’t go to like church or anything. I have a neighbor across the street from Syria and she insisted that her story was not interesting enough. I begged her and I still haven’t got her interview, but maybe I will.

But cold emailing and cold calling is difficult. I mean, people are maybe skeptical of what I’m trying to do, which is totally understandable, but it took me a while to find my interviewees, except Kate is my friend. We met at a mom’s stroller workout group.

I was really nervous about how I was preparing their stories, and so the conversations with each of them was a little bit different, but I made sure to get their blessings before ’cause it is so highly edited and there’s so much I could have included. So I made sure to get each of their blessings before I published them.

I got positive feedback from the participants about the films, especially Leah who spoke about Islam, our dance in the field. I think that I hadn’t spoken to her about what the plan was and just the whole nature topic was kind of unexpected to her and she found that to be a really beautiful interpretation.

All four of my participants felt like very self-conscious that their perspectives was very normal, everyday, nothing profound. But the grant allowed the time and resources to just put our energy towards this one person for this amount of time, and it is really powerful. So I feel like I’m inspired by that.

The most challenging part of this project was doing justice to some of the stories or the fear that we would impose ourselves in something we don’t fully understand. So Noelle’s piece is about borders and Palestine and people suffering. And we like sat around and watched news stories and read articles and felt like we were just scratching the surface and we were trying to question ourselves along the way, like, are we doing justice to this?

Or are we taking advantage of somebody’s story? So we just had to keep asking the questions and eventually just step into it and trust.

If viewers could take away one thing from my project or this conversation, it is that movement can teach us new things that we don’t already know.

Theme: It’s just, just a dream.

Alan Lawson: Hi, my name is Alan Lawson. I was born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio. And I’m a musician and a composer mainly focusing on violin and writing all sorts of music of many different genres. And for this showcase, I composed an orchestral piece called a Legacy. So Legacy was inspired by Martin Luther King’s March on Washington.

It was created in honor of the 60th anniversary. So it starts off a little bit, kind of like a spiritual and it transitions into a march and just a mixture of all sorts of American sounds, just to really try to evoke the feelings and just the tension that existed in time period back then.

I made it a film for the ArtsWave project because of the logistics of trying to get an entire orchestra to come perform it for the showcase would be just pretty difficult. So I filmed the performance and used clips of the rehearsals to make the film for that. I worked with the Cincinnati Symphony Youth Concert Orchestra for the performance. They actually commissioned me to write it for them.

It was really great to work with the Youth Symphony. A little bit over 10 years ago I was a member of the orchestra myself, so it was kind of like going back to my roots in a way and just seeing the progress that the youth have made since I was there.

The Freedom Center is a special place to me ’cause I’ve performed a lot here over the years, ever since I was a little kid. There was a sneak preview for some of the donors before this museum opened, and I was a part of a quartet that performed for the donors when I was about 10 years old.

Always performed at different events here and my high school had a talent show here. I’ve just, I’ve performed here so many times, so it’s pretty nice to be showcased as an artist here as well, along with everybody else. Honestly, just to be a grant recipient for this time program is really amazing. I’ve done nothing but want to create and have my works appreciated.

And this is just really the first time I’ve even had an orchestra perform a piece that I’ve written and I’ve been writing music for 26 years. So it’s just an amazing feeling. And on top of that, the orchestra performed the piece at Music Hall also. It’s something I’ve dreamt of for my entire life.

It was better than I’ve imagined. I hear everything in my head and also with the programs that I use, I can hear it played back, but to hear live musicians playing it in a live hall, just with the acoustics and everything, it was just absolutely amazing. I mean, I’ve been, like I said, I’ve been dreaming of this moment for my entire life and it’s really difficult.

So I’ve written a lot of pieces that have just never been performed and just to have this one is really special to me. Well, I was initially told about the grant by the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Youth Orchestra, and he said that if I were to write a piece for the concert, it would be a good fit for it.

So actually the grant itself is what inspired me to write the piece, Legacy. I just, I started working on it. As soon as I found out that I got accepted for it. I’m kind of an anomaly ’cause I’ve never studied composition. I just, I hear things in my head and I just write everything down. I start usually with writing out a melody, and as I’m writing the melody, I might hear the brass or woodwinds in the background and I just write as I’m going.

There’s no real structure or process to it at all. As I started playing with the themes, everything started coming together. I had no plan. Usually when I start writing music, I start with a blank slate, and as soon as I come up with something that sounds good in my head, I just build on from there. So from the beginning of the piece, it starts with music that’s inspired by spirituals.

Spirituals are like songs that slaves sung while they were in the fields, and a lot of them had hidden messages about how they wanted to get to freedom. I couldn’t think of one in particular, so I just kind of started humming a melody in my head and, and it just had that feeling to me, and I just decided to write it out and expand upon that.

So even later on in the piece, you’ll hear that same theme, but it’s in the form of a march. I am very biased as a violinist. I like to give everything to the violins because I always imagined myself playing the violin parts. I’ve been drawn to the violin for my entire life. I feel like in a past life I must’ve played violin or something because when I was a little over a year old, we have a home video of me telling my parents I wanted to play violin.

I don’t even think I knew what a violin was at that point. When I was two, I was seriously asking about it, and they took me to a violin shop and they said he’s too young. He’ll quit in like a month, take him back if he’s old enough and still wants to play. So they took me back when I was four and I just haven’t stopped since then.

For violin, I do a lot of everything. All right. Rock, hip hop. I play other instruments as well. I make all sorts of music, just whatever I’m feeling at the time. Throughout my entire life I’ve seen that music is something that brings people together. Any orchestra running, any just group of musicians, or even just going to a concert, you see people from all walks of life, all races, genders, religious beliefs, and they’re all coming together just to enjoy the music no matter what genre it is.

So I feel that with music, you can bridge everyone together and it just gives people a common ground. I would say that my piece is combination of the truth and healing because people will come together to listen to it, but also it will make you think just about that entire time period.

My own personal emotions are expressed through Legacy. I am a very emotional person and I think it helps me creatively. So whatever I’m feeling at the specific point in time in my life, I put that into my music. Actually while I was in the middle of writing this piece, I was diagnosed with kidney failure.

So, I put all of that into it. Like when I got out of the hospital, I just sat and wrote for like the entire like two weeks and completed it in a two weeks time period. So it’s been a pretty emotional journey for me. I felt like in a way it was therapeutic to just keep writing. Music has always kind of been like my therapy. When I got out of the hospital, I was just writing so much music. I finished the Legacy piece. I finished writing a symphony that I was working on. I just kept writing.

Well, one of the things that I hope that the audience will get from the piece is that people who look like them can also write music like this.

That was actually my initial plan when I applied for the grant. I wanted to go into schools and talk about the piece with the children and show them that they had opportunities and they could make music like this. And I was, that’s just something that I never saw a lot of growing up, and I thought that other kids would benefit from it.

And also to have a creative outlet where they could stay out of trouble and just express themselves in a healthy way. So that was my original plan and that was my original goal for the piece. Obviously things have kind of changed over the last few months from that, but, or this next year, I’ll see put that plan into action.

I always feel music is life. Music is everything. It’s like, it’s like the glue that holds the universe together. Music is love, so that’s kind of what I want people to take from it.

Theme: Just a dream.

Preston Bell Charles III: My name is Preston Bell Charles III. My film is called The Divided Roots, Seeing is Believing and I’m a native born Cincinnatian. Proud to be one.

Divided Roots, Seeing is Believing is a film art piece that is designed to illuminate some of the hidden history about Cincinnati, the good and the bad, and then also go into what it took for each one of the 52 individual neighborhoods to become a part of Cincinnati and how they developed in today’s time, whether it was a success, through access to railways and waterways, or any major construction projects that might’ve come through, or just how people were culturally accepted in different groups and maybe had to go form their own little area in order to thrive.

But many of us I found in Cincinnati either did not travel to a lot of different neighborhoods within our own city and therefore really didn’t have a knowledge of who might be just on the other side of a road or railroad tracks, if you wanna say it that way.

The intention of the film is to get people to travel from their neighborhood to another region. Just giving an example, I was riding the streetcar the other day a few days before coming down to the Freedom Center and two young gentlemen who I assume lived downtown, they were just talking amongst themselves and we had gotten to a certain point on the streetcar just north of Central Parkway, and they started discussing how they had never been that far north or that far up.

And I’m just like, wait, you live downtown but you’ve never taken a free streetcar closer to Findlay Market. And that’s actually a common theme, with a lot of Cincinnatians is a few people travel everywhere, but not really. A lot of people get around and I think that has a lot to do with the, not just increase in violence, but lack of empathy.

It’s hard to keep economies going when people aren’t going from one area to another, and the building of stereotypes and prejudices on both sides. So I’m hoping that when people get a little something to let them venture out into another neighborhood, they can let somebody else know that it’s safe and that our city can feel more cohesive through that exchange.

My good friend Donna Harris from the Over-the-Rhine Museum, she had been following my work and I had actually done some work for that organization. She inspired me. She was like, you should go out and submit a project. I was just like me? Like, what would I be submitting? I just like writing music and making people smile, but I also do have a lot of ideals, and when the opportunity presented itself, I’m like, okay, well this is gonna be a positive thing.

We’re trying to heal our environment. Cincinnati has a lot of good things. People just need help in bringing that goodness out, and it’s life changing to see my face or my name in different parts of the city. To be around people that are running nonprofit arms of these major companies. I can’t even say it was a dream coming true. I didn’t even see myself ever doing that.

The truth was illuminating things to me, like I didn’t know how the neighborhoods are formed, what makes a Black neighborhood, what makes a white neighborhood or Hispanic neighborhood? And I think that the actual facts and artifacts speak for themselves. And the fact that we’re in a different time where those things aren’t being created or necessarily destroyed, we can have a little bit of a springboard to maybe say like, okay, well what do we do going forward?

And the best way to know what to do going forward is to have the most input from a wider range of people to see how it can boost everybody’s world. So the healing will really think in one it’ll help with Northern Kentuckians. There are many northern Kentuckians who won’t cross the bridge because they feel Cincinnati is dangerous.

I know that it, it is a major city and that there are things that happen. But as a street musician, which is another way that I deliver art, I had not really been anything that would be unexpected outside of a dense population. And then in combination with having a strong passion for mental health, I try to look at too why these things happen and what can be done to prevent them in the future.

So really people getting to know each other helps reduce stereotypes, introduce new ideals. Some people in the city are very helpful, but they don’t know how their help can be utilized. And also when people don’t know what’s outside of their neighborhood, they end up locking themselves into a mental, physiological, almost like a prison.

You know, if there are no job opportunities in your neighborhood, well then maybe you need to go to another neighborhood to find job opportunities. Or did you know that the bus goes there? You know, every place in the film the metro bus goes to deliver a transportation. So it’s really just the hope that in some small way of people interacting. And this goes through my own personal life. I’ve been to every neighborhood except for two, which I found on the documentary, but now I’ve been there and I found success in meeting kind people, people that I can familiarize with, people that were supportive and I would’ve not known unless I would’ve ventured out and, you know, sought those opportunities.

The reason that why I had chosen to film for this project is that music, especially since I don’t sing, it does have its limiting effect. Somebody else would’ve had to put it into a visual, a medium, but really just to shed light on the flags that each neighborhood has to give itself identity. And to make it easier, I think to digest, I wanted it to be something that it could be observed in maybe a fifth or sixth grade classroom up until a high school level, and it’ll be released online through YouTube, and I know how visual things really wrap people into information.So it’s really in hopes to make sure that it can reach the broadest group of people and be most successful.

So my genre in the approach, it’s really called contemporary looping on the violin. That’s the official name. And I grew up in the classical realm, always loving classical music. Used to check out tapes from the library and that’s how I was trained in music. Give thanks to Ms. Gloria Wallace, who stuck with me all those years.

But when I had gotten further on, I, of course learned that orchestras were very difficult to get in, just like trying to join an NFL or NBA team. So I didn’t see myself in that route, but I loved music and how it affected people. So I just started going out, playing with the family at different events, things like that, weddings of co-workers.

And then when I got my first pedal, it was a DD-7 by Boss. That changed everything. I was able to record what I was doing live, do simple things over it. And when I exposed that to the city, people really loved it. So I became a somewhat of a live composer. I can go into an environment, feel the mood, and then try to amplify the ambience of that, just through the expression of music.

So that’s kind of what developed in my career today. And being able to write some scores, not just for this film, but I had done something for Michael Coppage a year or two ago, and other, works from museums outside of Ohio as well, to just add a little bit of a musical element to a history or an expository.

So I had discovered along my journey, the origins of a violin. And when I worked for Antonio Violins, I was a salesperson. Then I was a quality assurance person. Then they allowed me to start working on the actual, taking them apart, putting ’em back together. And one of the luthiers had told me, he’s like, yeah, this instrument started in Africa and nobody knows about it.

And I’m just like, okay, maybe he’s pulling my leg. Like I’ve been in this world my entire life and never heard this. And it was, it’s called the violdicamba. And I looked it up online and I was just like, oh wow. Okay. And then Bela Fleck, who’s a popular band, they actually went to Africa and did a documentary on the instruments and how they were sourced.

And when we look at bluegrass music, the violin, the banjo and the bass are main features of the music. Not the only instruments, but usually very prominent instruments in that genre and those instruments coming from Africa. But being assumed to be of the European culture actually showed more unification because in order for there to be a culture exchange in any way, shape or form, there has to be peace, camaraderie, love.

You don’t, you can’t take someone’s art forcefully and make it your own. You can duplicate it, but something would be lost. And it only exists in America in a pure form. It’s not a European art, like they have Celtic and other forms, but bluegrass in, in the essence of what it is, is uniquely American.

The truth that’s being expressed in my film is one, we don’t know enough to say that we know, especially about the person that we haven’t met. So we need to really change that thought process. And some things are the way that they are and it’s fine to accept that.

But really the expression of truth allows us to see another person and be able to see the relationship that would, that people actually have. We think that our truths are separate because we’re taught or indoctrinated that way, but everybody’s truth is interlinked when there’s a a problem or something good happening, it just gives people the opportunity to be a part of it in some way.

So you have to bring a person as close as possible to the situation in a comfortable way so they can be able to digest and at least say, okay, I see that now. That ties into me going to Appalachia when I decided to leave Cincinnati ’cause I was like, all right, this music thing is not going well. I don’t think people wanna listen to it too much.

And then I had this calling to go out there. My family thought I was gonna die. They thought I was crazy. You, you left your corporate job, why would you go out to the mountains? But I still look back at that as the greatest experience that I had met some of the greatest people.

They taught me about the history down there. And unfortunately, but fortunately, it was a little bit less racist in the Appalachia part of the country than it was here in my own hometown. So right around the time where my son was about to be born, it was a really strong drive to wanna come back and do something in a city like Cincinnati to make a difference.

Cause the people on Appalachia, there are some hard fighters. They know about all the social issues. And I was just like, wow, okay. We got showed up. They were using dial up internet, and I was just like, wow. It was, it just blew my mind.

So if I can go to Appalachia with no connections, and I went literally by myself, no friends or family, and not only make it out safe, but actually get great attributes to myself as a human being, I mean, it has to work the same way for others.

And that also is exemplified in the film. Like I’ve been in every neighborhood. People try to say I play everywhere now. I’m still humble about it. There’s places I haven’t played and anywhere that I do get to perform, it’s a blessing. But my success came from getting to know people. If I didn’t know people, I don’t see how a lot of things would’ve happened in life.

Helen Todd: Thank you for spending some time with us today. We’re just getting started and would love your support. Subscribe to Creativity Squared on your preferred podcast platform and leave a review. It really helps and I’d love to hear your feedback. What topics are you thinking about and want to dive into more.

I invite you to visit creativitysquared.com to let me know. And while you’re there, be sure to sign up for our free weekly newsletter so you can easily stay on top of all the latest news at the intersection of AI and creativity.

Because it’s so important to support artists, 10% of all revenue, Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized nonprofit that supports over a hundred arts organizations. Become a premium newsletter subscriber, or leave a tip on the website to support this project and ArtsWave and premium newsletter subscribers will receive NFTs of episode cover art, and more extras to say thank you for helping bring my dream to life.

And a big, big thank you to everyone who’s offered their time, energy, and encouragement and support so far. I really appreciate it from the bottom of my heart.

This show is produced and made possible by the team at Play Audio Agency. Until next week, keep creating.

Theme: Just a dream, dream