What is Art? Exploring Humanity’s Defining Passion

In this blog post, Jason Schneider discusses the elements and aims of the creative process. Then he dives into the limits and boundaries of art and its social dimension against the backdrop of A.I. and if the machines can create art.

Art is a Celebration of Human Consciousness

Animals and plants achieve transcendence by simply being present in their innate glory, moving through the life cycle, and fulfilling their biological destiny. For the most part they do not possess “second order consciousness,” an ability to perceive their lives “from the outside” as something distinct and separate from the world in which they find themselves, and from their perceptions of the events unfolding around them. Indeed, “separation” is the central theme of the legend of the Garden of Eden in the Old Testament, which is, in essence, a monitory myth recounting the birth of human consciousness and the perils of acquiring it. It reminds me of a cartoon I saw decades ago depicting Adam turning to Eve as they’re being evicted from the Garden of Eden and wryly observing, “We’re living in an age of transition.”

The transition recounted in Genesis entails “falling from grace” moving beyond the “unity” of a paradisal infantilism, and into the harsh dualities of the this and the that, right and wrong, the glory of life, and the inevitability of death, all of which are transmitted through the process of socialization and imparted in the context of human society. On this planet, only humans have gone through this process and evolved sufficiently to create conscious art, a physical and emotional representation and reflection of their experiences in living. A work of art, whether concrete like a sculpture, or as ephemeral as an improvised song, can convey elements of the consciousness of an individual artist or a group through time and space and elicit visceral emotional responses in others that interact with it.

In other words, art is a form of existential and emotional communication.

Humans create art almost as naturally as they breathe and we have done so even as hunter-gatherers. We have good archeological evidence from drawings and the remnants of ancient musical instruments that music and dance predate civilization, and it is significant that the vivid, brilliantly rendered cave paintings of animals at Lascaux France were executed about 17,000 years ago. The fact that these ancient “artists” of ages past were unaware of the modern concept of art is immaterial—they were expressing a fundamental human urge to create something that represents and transcends their lived experience.

Ars Longa Vita Brevis

This oft-quoted Latin epigram, frequently mistranslated as “art lasts, life is short,” is ascribed to Hippocrates, the renowned Greek physician. Its original meaning, loosely translated, is “skillfulness takes time and life is short.” In other words, “ars” or “art” is used here in its original meaning of technical skill or mastery, in this case referring to the art of medicine. Nevertheless, the idea that “art endures but life is short” reflects the contemporary view that art expresses and distills aspects of the artist’s consciousness in a durable form that remains accessible even after the artist is gone. A work of art is therefore, in some sense, un essai d’immortalité, an attempt at immortality.

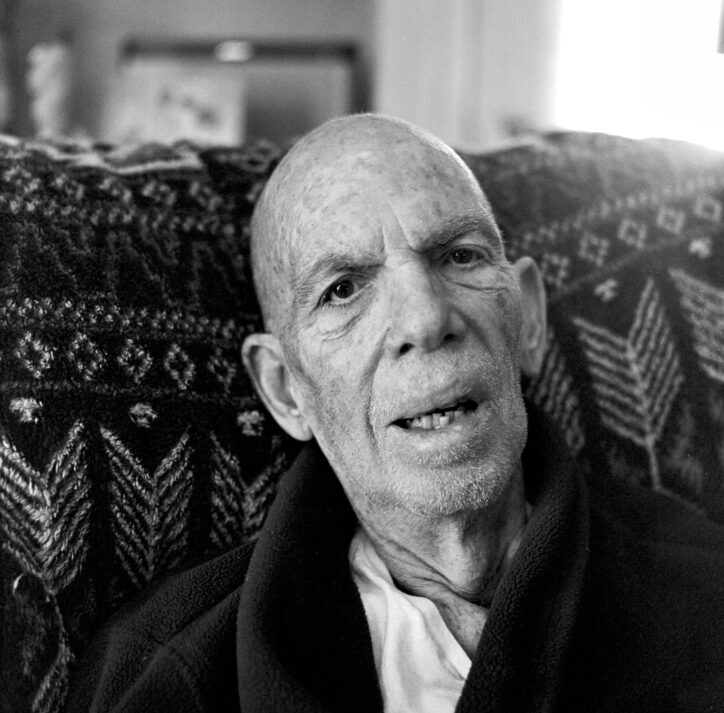

This concept was forcefully brought home to me in the mid 1980s when I ambled into the Rembrandt Room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. A group of high school students was listening to a lecture on the great Dutch Master given by their teacher. After about 10 minutes I was about to leave, when suddenly they departed, and I was left standing alone in the Rembrandt Room.

Having taken a two-semester survey course in The History of Western Art, I am familiar with the work of Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606-1669) and admire his painterly skill and mastery of lighting. However, I’m hardly a Rembrandt fanatic and I find some of his large canvases, though superbly executed, a little too grandiose for my taste. So, I passed by the monumental Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer and turned my attention to a relatively small (about 31 x 24-inch) painting labeled Rembrandt: Self-portrait, Age 60.

As I gazed into it, there was Rembrandt looking out at me over the space of more than 300 years. It was him, without self-aggrandizement, self-abnegation, or guile, bearing the inevitable marks of age but asserting his presence. If there is any “message” in this utterly straightforward painting it is simply, “Here I am.” And once I realized that I wept uncontrollably. The emotion that came over me was so strong, and I cried for him, for me, and for all humanity.

The only other painting that elicited a comparable emotional reaction in me was Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night. The genius of van Gogh is his uncanny ability to let you live into his world of heightened perceptions and see things through his eyes—a perfect example of transmitting one’s consciousness through time and space and evoking an emotional response in the viewer.

Ancient Aesthetics and The Concept of Art

While aesthetics was not officially codified as an academic discipline until the 18th century in Europe, the Ancient Greeks and Romans certainly wrestled with the problem of defining beauty.

Beauty is a crucial element in defining the concept of art because it enhances the accessibility and emotional impact of the artist’s creation on those who experience and interact with it.

The Greek word kalon, roughly equivalent to good or appropriate, was commonly used to signify beauty or beautiful and prepon in Greek and honestum and decorum in Latin were used similarly in philosophical texts.

The concept of proportion (how the parts of an object relate to the whole) was also said to be an important aspect of beauty, and this was called summetria, meaning appropriate or fitting proportionality, not merely bilateral symmetry. The Pythagoreans of the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.E. took this idea even further, positing that everything in the world can be explained in terms of numbers and the relationships between them, and that proportion and harmony are expressed in numerical relationships. The Pythagoreans argued that painting and sculpture achieve their ends by means of specific numerical ratios and were the first to pinpoint the mathematics underlying the Greek musical scale and attributing the beneficial effects of music to is harmonizing influence on its audience.

Mimesis and Catharsis: The Defining Elements of Fine Art

One ancient Greek term for art was techne, a much narrower term than “art” per se, that points toward the beauty of functionality as opposed to fine art in the modern sense. However, in referring to art, the Greeks also used the word mimesis, literally “imitation” in the broadest sense of “representation,” a concept that transcends mere copying, but also includes creative interpretation. While this is not exactly “fine art” in the modern sense, mimesis does convey the sense that fine art is created in the context of a cultural tradition, and that it is a reflection or expression of an individual or group consciousness—not life itself, but a representation of life that emerges from the experience of living and is intended to express and communicate key aspects of that experience to others through time and space.

Catharsis, famously described by Aristotle, refers to the psychological effect of art on the humans that experience it. While the philosopher offers no explicit definition of the term, he clearly describes it as a kind of transformative emotional process, citing the fear and pity experienced by the audience attending a Greek tragedy. He also observes that music should be a central component of education because it provides catharsis as well as other benefits. The Aristotelian notion that a person’s consciousness can be deeply affected by experiencing a work of art is consonant with the modern concept of art as emotional and existential communication.

Transcending the boundaries of time and space, a work of art can convey essential elements of the artist’s life experience and creative vision to other humans, enriching their lives and enhancing their perceptions.

When J.S. Bach was asked why he wrote music, he replied succinctly, “For the greater glory of God and the recreation of the human mind.” While the great composer was undoubtedly pleased that people enjoyed his music, he also hoped they would find it uplifting, as the original meanings of the word “recreate” suggest; “to refresh, restore, revive, create anew, or invigorate.”

Emily Dickinson: Art as Communication and Transcendence

The celebrated poem below (No. 441, c.1862) expresses, with masterful concision and restrained passion, how Emily Dickinson saw her work as the embodiment of her consciousness and as a “message” to future generations, an emblem of her immortality. The “letter” is an apt metaphor for art as the ultimate form of communication, in her case one that ironically employs words to transcend words. Her final request is to be judged “tenderly” by future readers, not for her poetry, but “For Love of Her,” that is Nature (the female aspect of the Almighty), the source of all, including her poetic genius.

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me—

The simple News that Nature told—

With tender MajestyHer Message is committed

– Emily Dickinson

To Hands I cannot see—

For love of Her—Sweet—countrymen—

Judge tenderly—of Me

Recording Media: Transforming the Ephemeral Into the “Eternal”

Based on contemporary accounts, the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were very well performed, Johann Sebastian Bach was the consummate organist of his time, and Jenny Lind was a magnificent operatic soprano. However, we can never know any of these things firsthand because they occurred before the invention of sound recording and cinematography. These media have enabled the performing arts to be recorded in the form of movies, records, CDs, and digital sound and image files, thus achieving the (relative) permanence of the plastic arts such as painting, drawing, and sculpture, examples of which have endured for hundreds and thousands of years.

While it’s great to be able to hear Pablo Casals play Bach’s cello suites and to experience Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dancing and singing their way across a stage set as they did on the silver screen, permanence or relative permanence are not essential in determining what qualifies as a work of art.

So long as there is an artist or performer creating art and an audience of at least one, the basic criteria of art are fulfilled.

Indeed, one can argue that the intentional creation of a work of art is sufficient unto itself, and while having an audience is clearly preferable, strictly speaking, it isn’t necessary.

I can recall sitting on a stool in a “dive bar” in Cologne, Germany in September 2016, witnessing a group of rowdy 20-somethings acting up and taking pictures with a cellphone camera. “Hey, look at Fritz drinking beer with his nose!” exclaimed someone as they passed the cell phone around to uproarious laughter. As soon as everyone had had a good look at the picture, they deleted it and started all over again. Does this utterly transient image qualify as art? Absolutely. It was a work of art the instant someone composed the picture and decided when to press the shutter release. How long the image lasted is immaterial.

Selectivity: The Essence of Artistic Creation

The unlikely answer to this critique is that the number of individual decision points entailed in creating a work of art is irrelevant so long as the artist’s intention can be articulated and shaped in a way that expresses the artist’s consciousness.

In other words, conscious acts of selectivity can accomplish essentially the same thing as the sculptor’s chisel or the painter’s brush.

The miracle of photography is that by controlling a minimum of two variables, what is in the frame, and what instant is recorded, that photographic works of art can be created. There are inevitably additional operational decision points embedded in each of these fundamental variables—the lens used, its coverage angle and imaging characteristics, the capture medium, the shutter speed, even the type of camera. All these factors determine exactly what the photograph will look like, but by controlling space and time, composing the picture, and determining which moment is recorded, photographers can express their personal vision of the subject and the world in which it manifests and transmit it to others. That is the very definition of the art of photography.

Limiting Cases: Two Thought Experiments

Imagine a security camera, mounted in a ceiling corner pointing downward, and positioned to record events occurring in a room, such as the lobby of a bank. As with most such installations, the camera is programmed to take a picture every few seconds. Now suppose the bank was robbed and I went through all the recorded images to see if I could find a clear picture of the perpetrator, but instead I ran across a picture of a husband and wife having an argument, showing the woman ripping a twenty-dollar bill to pieces. Would that humorously ironic image be considered art, and could I truthfully submit it to an art photography contest as my work?

Well, there were several decisions that had to be made before the image could be recorded—the exact position of the security camera, the coverage angle of the lens, the type and resolution of the recording medium, etc. If I installed the camera myself I would, in effect, be the one who “framed” the shot even if there were some degree of randomness in its composition. But the main reason I could rightly claim artistic ownership of the picture is that I selected it from literally thousands of frames, valued its significance as a visual statement, and presented it as an artwork. Even if a security company installed the camera, the acts of selecting the picture and exhibiting it as something worthy of attention by other humans places it in the realm of art.

What about an image produced by artificial intelligence (A.I.)? Can it ever be considered art, a creative work guided by the human consciousness of an “artist?” It depends.

So long as its creation involves some level of human agency—choosing a program, selecting which of several images is to be presented, applying tweaks to the initial image, or reprogramming based on revised criteria until the desired result is obtained—a work created by A.I. can indeed be a work of art attributable to an individual or group.

Generally, one must input a set of instructions or suggestions for A.I. to do its thing, and therein lies the human element. And even though the process may entail some randomness it is a human being that decides which images are worthy of being published or shown. Even if there were a hypothetical “A.I. machine” that just spit out images willy-nilly and automatically posted them on the internet, human beings would ultimately decide which of them were relevant, and these “chosen images” would, in the broadest sense, qualify as works of art.

Not All Art Was Created as Art

Much of what we now call art was created for other purposes—advertising, functional use, propaganda, spiritual devotion, architectural and personal ornamentation, etc.—proving that the definition of art, even in the 19th Century sense of “the fine arts,” is fluid and ever changing. Toulouse-Lautrec’s iconic Moulin Rouge posters were pasted on walls as advertisements for a fancy strip joint on the Left Bank of Paris, though hundreds of Parisians did buy them to hang on their walls. The magnificent WWI military posters from England, America, France Germany, and Russia were created to entice young men to join the army, but they now fetch stupendous prices at art galleries. Neither an original Coke bottle nor a vintage Harley-Davidson motorcycle was created as a work of art, but both are now displayed in major art museums all over the world.

The message: art is what society defines as art, but it’s also intensely personal—you know it when you experience it.

The artist produces artifacts accessible though the five senses and maybe the sixth as well. Creating art entails artifice—not deception, but the artfulness of creating a simulacrum, something that distills, intensifies, and stands for essential aspects of human life and the experience of living, but stands aside in all its glory, enriching our experience, enabling us to transcend the limits of our vision, and perhaps even our mortality.

Dylan Thomas: Art for Art’s Sake, The Primacy of Intention

I had the great privilege of hearing Dylan Thomas deliver the magnificent poem quoted below in an informal setting at Teacher’s College, Columbia University in 1952 when I was 10 years old. It expresses, with tragic and exalted intensity, that the artist’s essential role is to create art for its own sake, to express the truth of our common human experience, and to put it out there whether it finds an appreciative audience or not. The act and the intention alone are sufficient.

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.Not for the proud man apart

Dylan Thomas

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

He writes for “the lovers, their arms around the griefs of the ages” not for money or fame, but for “the common wages of their most secret heart.” And his poems are not aimed at litterateurs or academics but for those who “pay no wages, nor heed my craft or art.” When I asked my late great, daughter Heidi, a compulsive and adept poet, why she wrote poetry, she replied, “Because I can’t not write poetry.” That’s the best answer there is. Same for Dylan Thomas.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Comment by бнанс — May 7, 2024 @ 11:00 am

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Comment by Создать личный аккаунт — July 22, 2024 @ 6:02 pm

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Comment by Anonymous — July 25, 2024 @ 9:05 pm

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Comment by binance — August 8, 2024 @ 4:32 am

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Comment by ^Inregistrare pe Binance — October 15, 2024 @ 4:38 pm

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Comment by binance account creation — October 18, 2024 @ 6:22 pm

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://www.binance.com/ro/register?ref=V3MG69RO

Comment by criar conta na binance — December 15, 2024 @ 6:17 am

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Comment by Cont Binance — January 16, 2025 @ 3:57 pm

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Comment by binance sign up — May 15, 2025 @ 11:45 pm

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://accounts.binance.com/zh-CN/register?ref=VDVEQ78S

Comment by Anonymous — May 21, 2025 @ 2:39 am

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Comment by Buat akun gratis — August 2, 2025 @ 8:36 am