Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right: Ambiguities of the Heart

Bob Dylan’s 1962 masterpiece “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” is a simple, eloquent ballad that reveals, in excruciating emotional detail, the heart-wrenching experience of leaving a lover. The lyrics, all pointedly delivered to his female counterpart in the first person, convey the mixed emotions of heartbreak, harsh judgment, disdain, anger, grim determination, loss, and fading hope that are inevitably part of the process of separation. On the surface, the song comes across as a series of incisive “off-the-cuff” observations by a clever country boy going through a rough patch, but it is truly a literary tour de force that expresses the emotional texture of a universal human experience with consummate authenticity, perhaps revealing more about its author than he intended. Through his brilliant use of irony, passive aggression, wry humor, and wistful resignation, Dylan reveals the overwhelming and underlying sense of loss and heartbreak that belie his overt dismissiveness and determination to take decisive action by departing at dawn. The final stanza begins with “So long honey, babe” (a wistful reminiscence of better days) and concludes with the brutal “You just kinda wasted my precious time But don’t think twice, it’s all right.”

The expression “kinda” would normally function as a qualifier, but here it intensifies the bitterness of his imminent departure.

“Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” the title of the ballad, and “But don’t think twice, it’s all right,” the concluding line of each of the four stanzas, are oxymorons, phrases that, like a traditional two-word example, “sad smile,” simultaneously convey opposite meanings. Its denotative meaning is “Don’t give it a second thought; I’m OK with it,” but contextually, and emotionally, it expresses the converse, namely “This is NOT OK—it’s an inexorable tragedy I must endure.” It’s a classic example of Shakespeare’s timeless observation (uttered by Queen Gertrude in Hamlet) “Methinks she doth protest too much,” except that here the gender has changed. Indeed, this ironic duality permeates the entire work, revealing an inner heartbreak barely concealed by the assertive and judgmental utterances of an aggrieved lover determined to sever the relationship.

The first stanza lays out the premise of the song with masterful concision—the singer-protagonist is leaving his lover, she may not understand why but that’s irrelevant, and he intends to be gone by the following morning—presumably, he’ll sleep alone on the couch this final night. This is all laconically expressed in the folksy style of a country boy from Hibbing, Minnesota, an iron mining town (population 16,214 according to the 2020 census) where Dylan (née Robert Zimmerman) was raised in a middle-class Jewish family before moving to New York City in 1961 at the age of 19. However he may have evolved over the years, Dylan was legitimately a country boy when he penned these eloquent lyrics in 1962, and he makes effective use of country dialect. A good example is the second line, “If’n you don’t know by now.” “If’n,” a two-syllable vernacular expression, maintains the metric structure of the verse, and is also an emphatic form that highlights the meaning—his lover’s lack of understanding that will “never do somehow.” “When your rooster crows at the break of dawn,” is a charming image drawn from country life that obliquely refers to himself, a departing “rooster” who’ll be gone by the time you “Look out your window” at dawn. The mounting judgmental thrust is taken to its logical conclusion in the penultimate line, “You’re the reason I’m a-traveling on,” squarely placing the blame on his oblivious lover.

The second stanza begins with two couplets referring to “turning on your light,” a metaphor for radiating positive energy, validation, and love. Whatever constellation of meaning “light” may signify, it is a light “I never knowed” and “it ain’t no use in turning on your light” now because “I’m on the dark side of the road.” In other words, it’s too late to initiate a “charm offensive” (a trenchant oxymoron) because I’m now in a place that’s impenetrable to light. Then, in a remarkable turn, the disenchanted narrator suddenly reveals the inner emotions underlying his bitter rejection and harsh judgments, plaintively suggesting a possible reconciliation. “But I wish there was somethin’ you would do or say To try and make me change my mind and stay.” And fittingly, the penultimate line of the stanza is perhaps the most objective assessment of the underlying deficiency of this doomed relationship, “But we never did too much talking anyway.” That is, the absence of sincere and heartfelt communication.

The first four lines of the third stanza reiterate the theme set forth in the second stanza, except that the “unreceivable message” here is aural rather than visual. “Calling out my name” is essentially a plea for attention from and connection with another and is also an implicit validation of the other’s presence, identity, and personhood. But even the attempt is “pre-butted” as a dubious ploy, vitiated by the damning phrase, “Like you never done before.” And even if her motives were totally sincere, any attempt at connection would be out of the question because “I can’t hear you anymore.” This overwhelming sense of detachment and isolation is epitomized in the following lines that evidently occur to him as he’s “a-thinking and a-wonderin’ walking down the road.” Significantly, line 6 is delivered in the passive voice, the first part stating that the relationship as over, “I once loved a woman,” followed by “a child I am told,” a speculative judgment by unspecified others (who presumably know her) bashing the rejected lover as immature, and implicitly self-centered. The next line, “I give her my heart but she wanted my soul” implies that his lover wanted more than she was entitled to, that her expectations were unrealistic.

Were they? It all depends on how each party defines a love relationship and what each expects to get out of it. If one wanted a soulmate, someone with a deep, almost magical connection, a sense of unspoken understanding, comfort, acceptance, and alignment, while the other was looking for a pleasant and supportive paramour, the relationship would be likely to unravel at some point. And despite all the recriminations, blame-shifting, and hard feelings so brilliantly articulated in the lyrics, this specific breakup may well have been preordained from the start and not really anyone’s “fault”. At some level, I believe Bob Dylan understood all these things, which is why he was able to capture the inconsistencies, ambiguities, and impermanence of so many love relationships, creating and delivering one of the greatest “breakup” songs ever written.

The fourth and final verse of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” is fittingly succinct and utterly devastating. The first couplet, “So long honey, babe Where I’m bound, I can’t tell” begins with terms of endearment, and concludes by stating, in an almost self-pitying manner, that his object is simply to go away, with no specific destination or plan in mind. “Goodbye’s too good a word, babe So I’ll just say, “Fare thee well,” are the most striking and transcendent lines in the entire song, simultaneously revealing Dylan’s mastery of defamatory rhetoric and his deep knowledge of etymology. “Goodbye,” a late 16th century contraction of “God be with ye” that also implies “till God brings us together again,” is a very good word indeed, one of the loveliest, most heartfelt, meaningful, and commonly used expressions in the English language. That’s why it’s “too good a word” for marking this agonizing departure. “Fare thee well,” an old-fashioned, more formal version of “farewell,” is deemed more appropriate here precisely because it is less personal, less emotional, and more down-to-earth. “Farewell,” from the 14th century Middle English “farewel,” derives from the Old English “farin” (from the Germanic fahren) which means “to journey” and “well” which, in context, means “safely.” So, essentially, Dylan is wishing his soon-to-be-erstwhile lover safe travels rather than God’s blessings. When you consider the incisive brilliance of these lines (and of course countless others) one can understand why Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. He earned it.

The concluding four lines of the sad ballad provide exactly what is required and expected: a powerful, savage conclusion. It begins with a semi-conciliatory phrase, “I ain’t a-saying you treated me unkind,” and continues with a snide, somewhat disingenuous jibe “You could’ve done better but I don’t mind.” before delivering the coup de grace, “You just kinda wasted my precious time.” Since humans have the tragic knowledge that we move inexorably along the cycle of birth and death, we know that our time is short and all we have. That’s why time is “precious” and why the most appropriate way to deal with a lover whom you believe has wasted your time is severance. So, like Brutus, Dylan concludes his brilliant and impassioned litany of reproofs with “the most unkindest cut of all.”

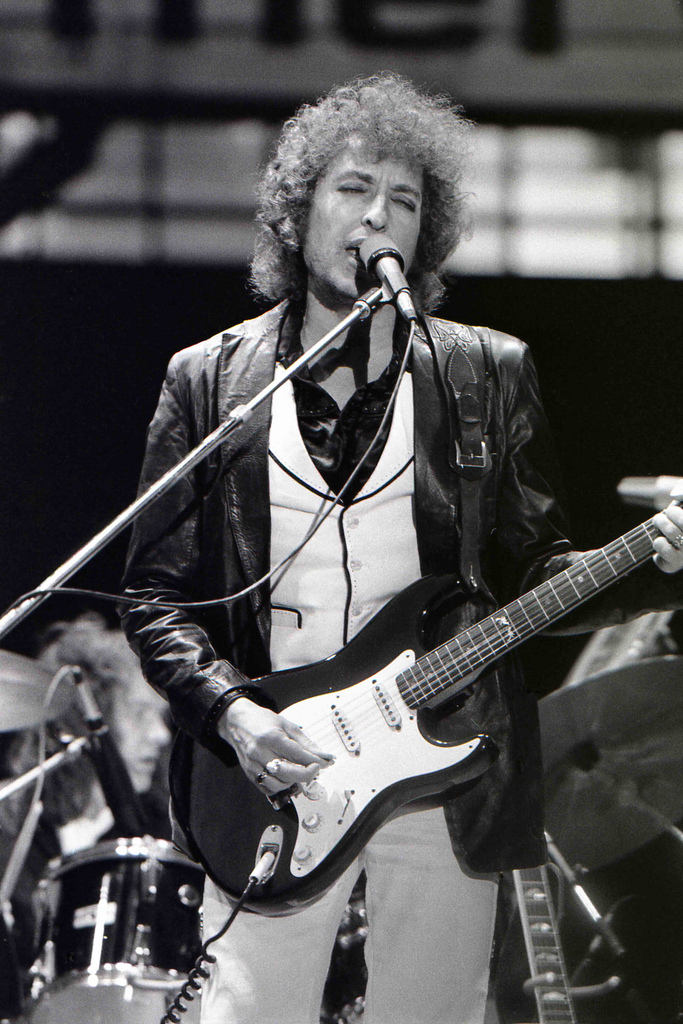

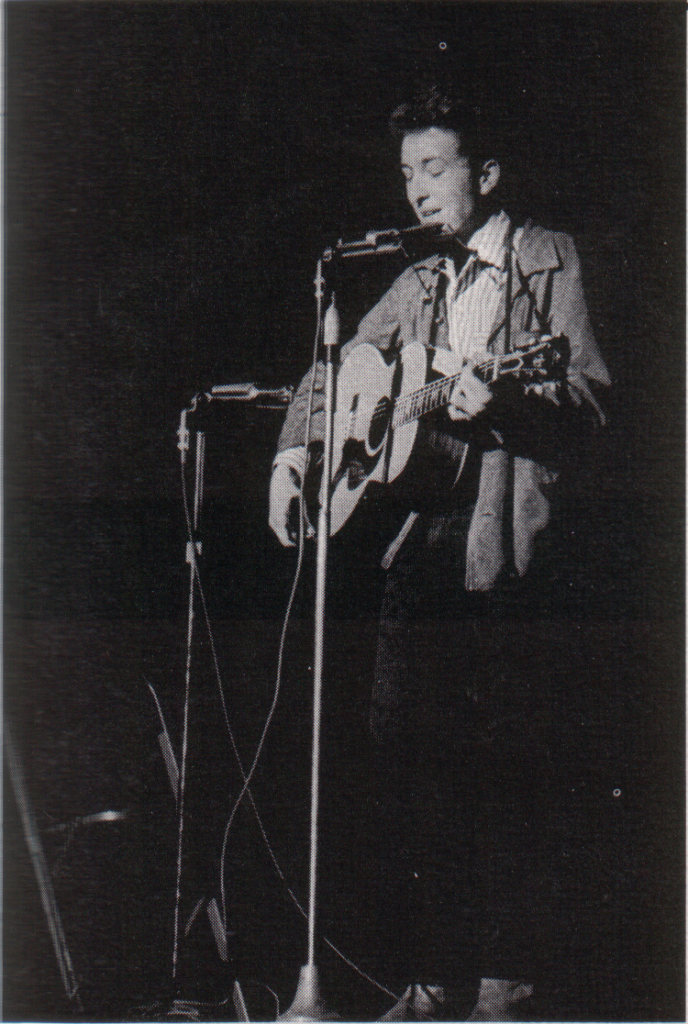

To fully appreciate “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” you must listen to the official studio recording released in 1963. It is a timeless masterpiece delivered to perfection, both vocally and instrumentally (acoustic guitar and harmonica) by a consummate artist who famously “doesn’t have such a great voice” but whose performances are often unmatched in their emotional impact and authenticity. His understated but expressive phrasing and disarmingly straightforward delivery are exquisite, and it comes across as a very sad song, which, of course, it is.

Historical background

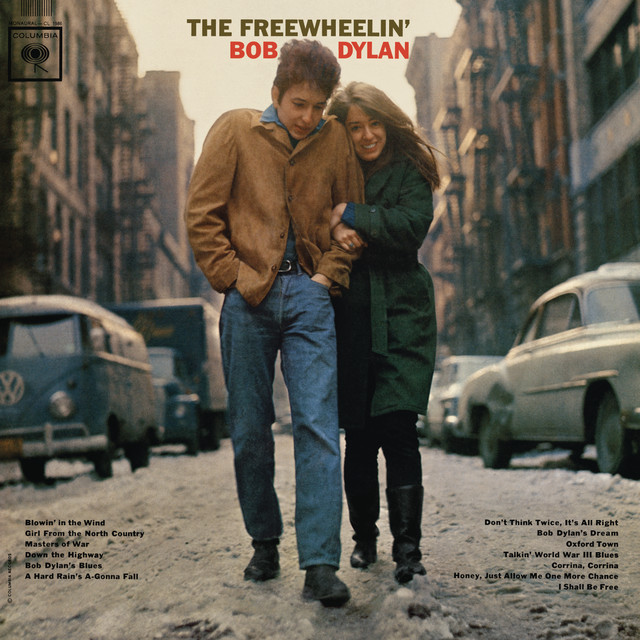

While many have speculated on the identity of the woman who inspired “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” Dylan himself has confirmed that Suze (pronounced “Suzee”) Rotolo (1943-2011), his girlfriend from 1961-1964, “had a strong influence on his music and art during that period.” An American artist specializing in artist’s books, Rotolo is the woman who appears walking with Dylan on the cover of his 1963 album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Dylan’s extended separation from Rololo while she attended the University of Perugia in Italy is said to have inspired several of his finest love songs, including Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right, Tomorrow is a Long Time, One Too Many Mornings, and Boots of Spanish Leather. However, while art is often described as an “imitation of life” (mimeis in Ancient Greek), art is also transformational and inventive. That’s why the phrases and images in Bob Dylan’s love songs are often markedly different from the events that may have inspired them.

Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right

It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe

If’n you don’t know by now

And it ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe

It’ll never do somehow

When your rooster crows at the break of dawn

Look out your window and I’ll be gone

You’re the reason I’m a-traveling on

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

And it ain’t no use in turning on your light, babe

That light I never knowed

And it ain’t no use in turning on your light, babe

I’m on the dark side of the road

But I wish there was somethin’ you would do or say

To try and make me change my mind and stay

But we never did too much talking anyway

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

So it ain’t no use in calling out my name, gal

Like you never done before

And it ain’t no use in calling out my name, gal

I can’t hear you anymore

I’m a-thinking and a-wonderin’ walking down the road

I once loved a woman, a child, I’m told

I give her my heart but she wanted my soul

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

So long honey, babe

Where I’m bound, I can’t tell

Goodbye’s too good a word, babe

So I’ll just say, “Fare thee well”

I ain’t a-saying you treated me unkind

You could’ve done better but I don’t mind

You just kinda wasted my precious time

But don’t think twice, it’s all right.

Bob Dylan