Ep19. ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Part 3: Artists

Creativity Squared is proud to share the third part of a special series with our partner ArtsWave. If you haven’t already, check out Ep13. ArtsWave Truth & Healing Part 1 and Ep.16 ArtsWave Truth & Healing Part 2. These podcast episodes highlight the phenomenal artists and grant recipients selected for this year’s ArtsWave Black and Brown Artists Program!

Today’s podcast focuses on the vision of five artists for the world they want to live in and expressed through their art. You’ll hear about (each of these links to their accompanying blog post for each artist):

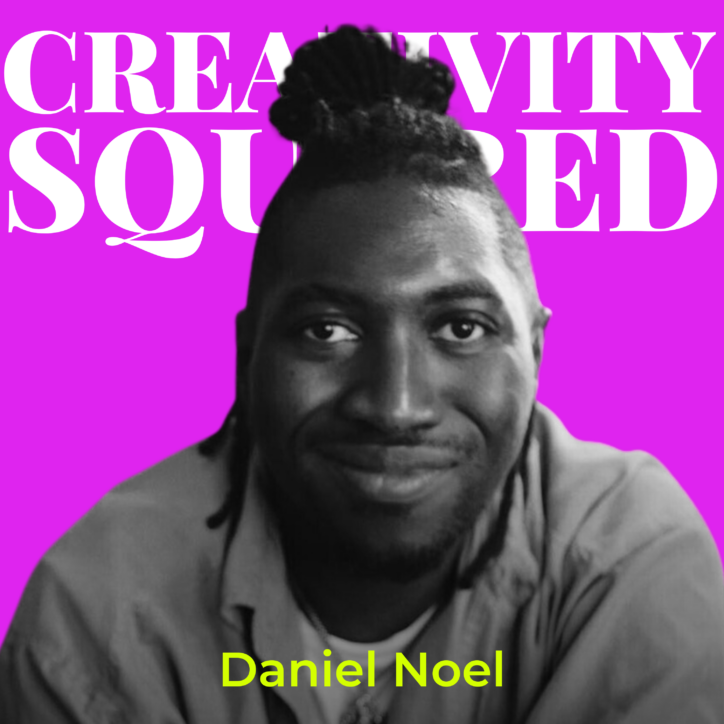

- “Nomad” by Daniel Noel, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “TLACUĀ PAHTIĀ” by Rebecca Nava Soto, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Pato y Muerte” by Gabriel Martinez Rubio, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Historical Perspectives on Urban Renewal in Cincinnati: A Community Retrospective” by Deqah Hussein-Wetzel, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “FLIPd: Cincinnati, Ohio’s Historic Places, Spaces told through African American Stories” by K.A. Simpson, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

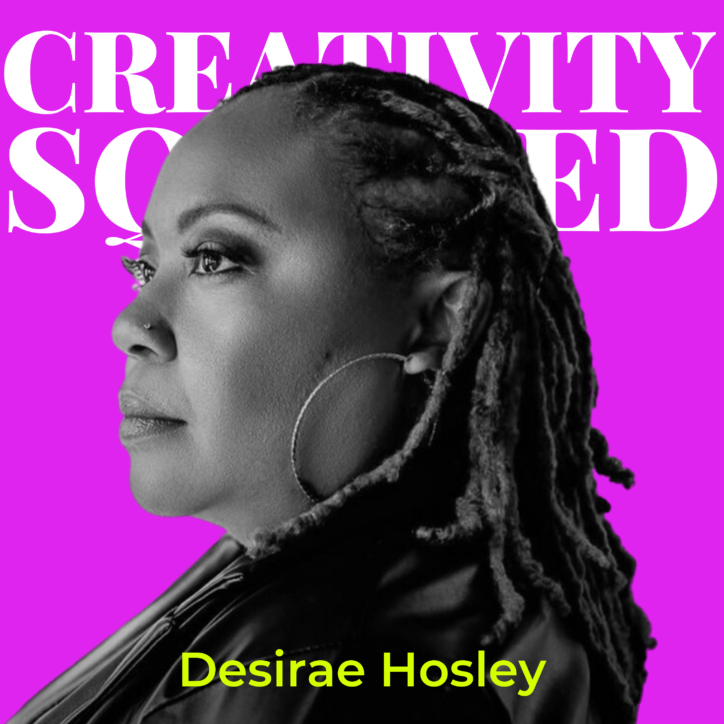

- “Social Therapy: Are We Healing?” by Desirae Hosley, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

They all talk about their individual projects and how they fits into this year’s theme “Truth & Healing.”

Who Is ArtsWave?

ArtsWave is a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists. Because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue generated from Creativity Squared goes to ArtsWave to support their Black and Brown Artists Program. The mission of Creativity Squared is to envision a world where artists not only coexist with A.I., but thrive.

And in case you missed it, listen to Episode 9 of Creativity Squared featuring Janice Liebenberg who is the Vice President of Equitable Arts Advancement at ArtsWave to hear her talk about how the arts can bring people together and for more on ArtsWave.

Truth & Healing Showcase

We had the honor of interviewing all of the artists at the opening of Truth & Healing Visual Art Exhibition, which is on display through September 10 at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center’s Skirball Gallery in Cincinnati, OH. It’s truly an inspiring, humbling, and grateful privilege to share their stories with you.

This year’s Showcase is focused on the themes of healing, rebirth, and reconnecting. Projects explore and build upon the current artistic commentary of health and race and connect it with historical events and visions of a more equitable future.

This year’s Black and Brown Artists Program cohort reflects a vibrant collection of diverse art forms created by an equally diverse group of 18 artists. Their mediums include couture fashion, painting, and sculpture — along with film, musical composition, podcasts, theater, dance, and multidisciplinary works.

The projects not only represent the African American experience, but also the experiences of those with Mexican, Lebanese, Somali, Argentinian, Zimbabwean, Guatemalan, and Indigenous heritage.

The intention of these interviews is to give these artists another platform to share their art and the truth expressed through it, as you never know what ripples will turn into waves.

Full Artist Video Interviews

Each podcast episode in this series will have accompanying videos with the full interviews with each artist. Watch them here or on our YouTube playlist. Each also links to an artist-dedicated blog post too.

“Nomad” by Daniel Noel, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

“My goal is to create a space where my ability to thrive does not impede your ability to thrive.”

Daniel Noel

Daniel Noel’s work as a musical and visual artist explores his complex relationship as a first-generation immigrant navigating his adopted home while seeking to find love, healing and community in a culture grappling with a complicated history.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Daniel.

“TLACUĀ PAHTIĀ” by Rebecca Nava Soto, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

“And always remember, YOU ARE the medicine.”

Rebecca Nava Soto

Rebecca Nava Soto is a multidisciplinary Xicanx artist based in Ohio. She uses mixed media painting, digital media and ephemeral installations to explore themes of perception, writing/iconography/language, technology, healing and mysticism.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Rebecca.

“Pato y Muerte” by Gabriel Martinez Rubio, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

“Being part of the Hispanic community or the Latino community here, it is very important for me to be part of this program. Little by little, we’ll open doors for the people who will come behind us.”

Gabriel Martinez Rubio

Gabriel has developed his career as a dancer and choreographer between Mexico and the United States, working with different dance and theater companies, including Cincinnati’s Mutual Dance Theatre.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Gabriel.

“Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal” by Deqah Hussein-Wetzel, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

“In an ideal world, I would love for urban planning to truly involve community engagement.”

Deqah Hussein-Wetzel

Deqah Hussein-Wetzel is an artist, preservationist, and urban historian who uses creative and innovative mediums, like her podcast Urban Roots, to uplift and amplify Black voices. As co-host/producer of Urban Roots, her work dives deep to unearth little-known stories from urban history by speaking directly to communities impacted by top-down urban planning practices like urban renewal and gentrification. Deqah is also the founder of an anti-racist community preservation nonprofit called Urbanist Media which seeks to elevate underrepresented voices by helping preserve the stories and places significant to people of color.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Deqah.

“FLIPd: Cincinnati, Ohio’s Historic Places, Spaces told through African American Stories” by K.A. Simpson, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

“History is never really one-sided.”

K.A. Simpson

Kareem (K.A.) Antonio Simpson is an author whose work challenges the notion of societal norms. His work has been published and exhibited across the USA and throughout the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring K.A.

“Social Therapy: Are We Healing?” by Desirae Hosley, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

“I am healing because I want to breathe unapologetically.”

Desirae Hosley

Desirae “The Silent Poet” Hosley was born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio. Known for being the quietest person on the scene, it’s astounding to see such a little lady with such a big voice that packs a powerful punch. She is a spoken word artist, motivational speaker, actress and community organizer. After being a peer advocate and rape crisis counselor, her poetry helps the reader to open their hearts and minds. Applauded for not being apologetic for any of the words that come out of her mouth, this has helped her be fearless and attain many of her great accomplishments.

Click here for the accompanying blog post featuring Desirae.

Support Artists and Stay Tuned for More

If you’re interested in working with, featuring, or supporting these artists, please don’t be shy about it.

Links Mentioned in this Podcast

- “Nomad” by Daniel Noel, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “TLACUĀ PAHTIĀ” by Rebecca Nava Soto, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Pato y Muerte” by Gabriel Martinez Rubio, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal” by Deqah Hussein-Wetzel, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “FLIPd: Cincinnati, Ohio’s Historic Places, Spaces told through African American Stories” by K.A. Simpson, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- “Social Therapy: Are We Healing?” by Desirae Hosley, ArtsWave “Truth & Healing” Artist

- ArtsWave’s Website

- Follow ArtsWave on Instagram

- Truth & Healing Visual Art Exhibition

- Truth & Healing Film Festival

- Ep9. Janice Liebenberg: Art Bridges Cultural Divides

- Ep13. ArtsWave Truth & Healing Part 1

Continue the Conversation

Thank you to all of the artists for being our guest on Creativity Squared.

This show is produced and made possible by the team at PLAY Audio Agency: https://playaudioagency.com.

Creativity Squared is brought to you by Sociality Squared, a social media agency who understands the magic of bringing people together around what they value and love: https://socialitysquared.com.

Because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists.

Join Creativity Squared’s free weekly newsletter and become a premium supporter here.

TRANSCRIPT

Desirae Hosley: I am healing because I want to breathe unapologetically. I am healing because I need to embrace love again. I am healing because I deserve to be loved. I am healing because I feel that I am not worthy of taking up space. I am healing because I see the piece of me that is ready to shine bright. I am healing because I love myself way too much to hold back.

I am healing because my daughter is watching. I am healing because I am tired of feeling that I am not good enough. I am healing because I can grow from my past. I am healing because I choose peace of mind.

Theme: But have you ever thought, what if this is all just a dream?

Helen Todd: Welcome to Creativity Squared. Discover how creatives are collaborating with artificial intelligence in your inbox, on YouTube, and on your preferred podcast platform. Hi, I’m Helen Todd, your host, and I’m so excited to have you join the weekly conversations I’m having with amazing pioneers in this space.

The intention of these conversations is to ignite our collective imagination at the intersection of AI and creativity to envision a world where artists thrive.

Today we have part three of our special three-part series highlighting the phenomenal artists and grant recipients selected for this year’s ArtsWave Black and Brown Artist program.

For the full video versions of these conversations. Visit creativitysquared.com or the Creativity Squared YouTube channel. And if you haven’t already, sign up for our free weekly newsletter so you don’t miss any news at the intersection of artificial intelligence and creativity.

The mission of Creativity Squared is to envision a world where artists not only coexist with AI but thrive. In this episode, we’re focusing on the vision of six artists for the world that they want to live in and as expressed through their art.

Daniel Noel: My name is Daniel Chimusoro.

Rebecca Nava Soto: My name is Rebecca Nava Soto.

Gabriel Martinez Rubio: My name is Gabriel Martinez Rubio.

Deqah Hussein-Wetzel: My name is Deqah Hussein-Wetzel.

K.A. Simpson: My name is K.A. Simpson.

Desirae Hosley: I am Desirae Hosley.

Helen Todd: We’ll be hearing from these artists whose projects were shown in the ArtsWave Truth and Healing Showcase and Film Festivals. Part one of the series features the artist whose work is in the exhibition that is available for visiting at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio through September 10th.

From Episode 9 on the show, Janice Liebenberg, who is the Vice President of Equitable Arts Advancement at ArtsWave shares:

Janice Liebenberg: And for us, a blueprint for collective action includes that the arts bridge cultural divides, and that is, you know, so key for us as we invest in the arts and how we schedule our programming and how we just feel that the arts can bring people together. No matter what divides us outside of the arts, the arts can bring us together.

Helen Todd: Creativity Squared is a proud partner of ArtsWave. And because it’s important to support artists, 10 percent of all revenue Creativity Squared generates goes to ArtsWave, which is a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists.

The intention of these interviews is to give these artists another platform to share their art and the truth expressed through it, as you never know what ripples will turn into waves. If you’re interested in working with, featuring, or supporting these artists, please don’t be shy about it. With that, here are six vignettes of our conversations.

Enjoy.

Daniel Noel: My name is Daniel Chimusoro. I perform under the artist name Daniel Noel. I was born in Zimbabwe, immigrated to America in August of 2006, and the piece that I presented was entitled Nomad.

Being a grant recipient for the Nomad album has really been an eye opening experience and a freeing experience because it allowed me to actually be able to put the necessary time and resources to be able to like see it through.

I’ve been a musician in the Cincinnati area since we moved here, but due to financial constraints, I could never afford to put out an album. I’ve done smaller projects in the past, but to be able to have like the funding and the resources to be able to like see the whole project through in a way that I would be like proud of, that’s been really, really encouraging and kind of given me more wind in my sails, if you will, to push forward and kind of explore the next chapter of my artistic journey.

Nomad the album was inspired by my journey as an immigrant. I was originally born in Zimbabwe and I lived half of my life there. I just hit that marker where now I’ve lived more of my life in America than I have in Zimbabwe. And so the album is a result of the journey that I’ve been on as a person in searching of like community.

I come from a community-orientated people. And so when you’re an immigrant, you kind of get shot sent like straight into like a cold water, if you will, like an ice bath of like, okay, now I got to try to find my community. And there tends to be some polarized spaces. And so trying to navigate that and seeing yourself in different spaces and being like, oh man, like I love this, but historically this is only attributed to this people group.

And then also, I love doing this, but I can only do that when I’m around these kind of friends. And so the process of making Nomad kind of allowed me to be able to bring together all the different people in my life that come from various different backgrounds that normally wouldn’t coexist in a space and the songs have been birthed out of that journey of like, okay, cool, music became that glue and it became that community and allowed me to find other like minded people that regardless of your background was, you found common themes that you related to.

Everyone relates to heartbreak. Everyone relates to wanting to feel like part of a community. Everyone relates to that, to that journey and to those different things. And so Nomad the album was kind of inspired by, by that journey and the finding of community and the building of community as a nomad.

When I found out about the grant, I had already been going on this self-exploratory journey. And so it was more of like serendipity kind of lining up and being like, okay, I have all these songs and my life is about this. And then also knowing like, oh man, like this now is also the open door for me to be able to walk in and then be able to like create a space where other people can experience that same healing that I’m searching for and we can begin to heal each other in that process.

So I’ve grown up being a fan of different styles of music coming from Zimbabwe we have sungura, we have Afro jazz, we have Afro beats and all those kinds of musical genres. But then my dad was very intentional about making sure that we listened to jazz, like regular jazz.

We listened to Eric Clapton. We would listen to Bill Gaither. We would also listen to Fred Hammond, Kirk Franklin. We would also listen to Usher. We would listen to 50 Cent and against my parents’ wishes, Bob Marley was a staple in our household.

So for me growing up in that environment, like, my music tastes and me as an artist has been shaped by that because I whenever I try to pigeonhole myself I literally can’t because I will be able to like the closest that I can get is like, okay, maybe I can write four or five songs that fit just this thing.

But more of the time it’s like man, like I really love being able to continue to explore as an artist. That’s how I would describe it as just like a musical nomad who like is just trying to be more one with himself, but also share music that allows people to connect regardless of the varying backgrounds of musical taste that everyone has.

So part of my musical process is like, I value the down moments and the quiet periods because that allows me to study, that allows me to take in life as it’s happening. And so through that, I study different producers. So I’ll study Mark Ronson, I’ll study Malay who does a lot of Frank Ocean stuff. I’ll study Quincy Jones, I’ll study like even go into different like musical artists and different time periods. And then also that that informs kind of the musical elements of it.

I’m also a visual artist. And so cinema plays a big part in my upbringing. And my dad also dabbled in like films and my brother also like does that. And so being able to watch a visually appealing story and be able to pick up on the subtext and the different stories that are being told at the same time, that’s part of my process and then when it’s time for me to kind of distill all that into one, I’ll also kind of look at the experiences that outside of what I’m going through, what are my friends going through?

What are the conversations that we’re having? What are we trying to say that we may be afraid to say at this particular moment or what are things that we want to say that we’re not hearing other people talk about as much? And so all of that kind of plays a big role in how I make music because that’s where the, for me, that’s where the art is.

I think the lyrics, it does vary song to song. So sometimes I start a song with the lyrics and I have this idea and this theme that I want to talk on, talk about, and I search for the musical pairing for that or the instrumentation that’s going to fit that. Oftentimes there are moments where like I have songs where it’s like, okay, this is a heavier subject to deal with, how can I make it less heavy for myself as the performer?

Because I am going to live with these songs and I’m going to share these songs in a lot of different spaces. You can’t always do that, right? Like, sometimes you have to actually sit in the discomfort because that’s where you start to have the necessary conversations, but then there’s also kind of, for me, self-care is a big part of it, and so being able to understand like, yes, I can do that, but there’s also moments where like, to care for myself, I need to find that balance of like, okay, maybe we pair this really dense lyrical matter with something that’s more light, upbeat.

The Beatles were notorious for doing some stuff like that where they would have super like deep, meaningful lyrics, but then underneath the music it was very light and it made it easier for people to engage. Comedy has a similar effect where you laugh at the jokes that are being told, but then it’s after the joke and the laughter is worn off that you start to think about the deeper truth that surrounds all of it.

And so, for me, I view lyrics and instrumentation through that lens of like, okay, depending on what the song needs and where I’m at as an artist, and what I’m sensing the community around me is needing, if we need just healing, which is part of the theme, like, then I’m gonna make sure that the music that I’m bringing and the instrumentation, both the lyrics and the instrumentation, cater to that because I want to create a space where people can be able to, like, take it in and be able to walk away lighter because oftentimes that may not be the case, like, we’re stressed out with bills, we’re stressed out with all these life emergencies, right?

We go through very trying things and so being able to create a space where people can take in that music in a way that leaves them feeling better or more encouraged. And then also sometimes when it’s just like, Hey, we got it. We have to talk about this. It’s uncomfortable, but for our relationship to progress, we have to deal with this particular thing.

And then once we’ve dealt with that, there’s freedom on the other end of it.

I’m Black and I’ve learned that there’s different meanings of Black. So coming from Zimbabwe. African Black slash African American Black, they’re looked at differently. I don’t view it that way. I think we’re all part of the same package.

And so for me, what I’ve, one of the truths that’s been freeing to, to kind of live in is like, there is no housing the Black experience. And me being a Black person. And so, in the same way that I can share and create music that relates to people that don’t look like me because they’re more drawn to indie music or pop music, in the same way that doesn’t put a lid on my expression as a Black artist.

I can write indie rock songs, I can write R&B songs, I can write hip-hop songs because those all share different stories and different truths that I’ve lived in and so that’s been a freeing experience to be like, okay, I don’t, I don’t care how you’re going to take me in as a Black man, I am going to create and I’m going to create from all of the things that inspire me and all of the things that are available and all of the different muses that I have.

And I’m going to express the truth that I need to express to free myself, and in turn that helps free others. And so that’s been the first truth that I’ve discovered through this process. The other truth that I’ve discovered is that we’re all, in a sense, nomads. We’re all looking for community. We’re all looking for people that can connect with us, that can build into us, that can help us heal, get to different junctures and different journeys.

We all have fears that we have that keep us up at night and that we’re all trying to just get through at the end of the day. And so knowing that looking at people that look different from me, it encourages me to like, kind of be like, okay, there may be things that you’re struggling with right now where it’s like, I’m trying to get you to understand my viewpoint of what I’m going through as a Black man in this country.

But understanding that fear sometimes operates in a way that keeps us from being able to see the other person on the other side. I am no different from your son, daughter, cousin, uncle. I go through similar experiences and my goal is to create a space where my ability to thrive does not impede your ability to thrive. The two can coexist.

Oftentimes we have a fear that me sacrificing means that I’m no longer able to thrive. And that comes from what I believe is a scarcity mindset. And an abundance mindset understands that there’s room for all of us to thrive. In fact, when we are able to lift up the least of us, we’re able to solve a lot of the issues that we typically would not be able to address because of the fact that we are now taking care of the least of us, and the people that are better off will still remain better off, creating a place for all of us to be able to recognize that everyone being able to live in abundance does not mean that you have to live in scarcity.

Rebecca Nava Soto: My name is Rebecca Nava Soto, and I am a multidisciplinary Chicanx and Latinx artist based in Cincinnati, Ohio. I use ephemeral materials, mixed media materials that continue lineage of art making practices in history rooted in my Mesoamerican indigenous background. Some of the themes that I explore are language, specifically pictographic language.

I’m really inspired by Mesoamerican writing systems, this process of abstraction from the natural and manmade world that dates back thousands of years. So these images were brought down into the most salient point to create this sort of abstract pictographs that communicate words and meanings. So I’ve been really inspired by that pictographic language and creating some of my own based on the way that my ancestors did it.

I’m working currently on a project about land rematriation in the Americas. But also most recently, the 2023 ArtsWave Truth and Reconciliation Grant for Black and Brown Artists, my project was titled “TLACUĀ PAHTIĀ”, and the title means in Náhuatl, which is an indigenous language that originated actually around the Four Corners area of South America and down all the way into Central America.

And so my project was done in collaboration with the Welcome Projects, project of Wave Pool Contemporary Arts Center in Camp Washington, Cincinnati, residency, food and art residency that they host. I was awarded that and it was such a pleasure to be able to work in Camp Washington that with that incredible organization, just this beautiful microcosm of what is possible for art and artists in the community and meeting community needs.

I really, uh, just was so honored to be chosen to be part of that residency. So that residency blurs the edges of food and art. And so part of my connection that’s always been there to my indigenous heritage, really is the, the food that I grew up eating with my grandmother’s cooking in Mexico, particularly.

And then of course, my mother’s cooking here as we migrate as they immigrated to the Midwest, Chicago, and then Cincinnati, really, that was the link that was our day to day to have that kind of food connection. And so she was a source of inspiration for me and that these ingredients and what we call Mexican food is really indigenous food, really.

Interestingly enough, I went to the Four Corners area, Southwest Colorado to do a research project this summer and like the same foods, the same grinding stones, I mean, it’s all there. It’s the same. And there’s this long connection between all of the Americas of food being the source of ties, strong ties to indigenous heritage.

So the whole installation was really a poetic response to the healing connection between indigenous foods and medicine and earth medicines and practices, a kind of honoring of my mother’s cooking of María Sabina’s poetry and her life and who she was and thinking about how to honor her and honor many, many people just like her. She was the famous one.

I was awarded the grant, and so it was like two part support by the art residency, food and art residency at the Wave Pool’s Welcome Project, and so I had the whole space to create an immersive experience. I think I saw maybe in a blurb or something as part of their residency that said immersive, and I thought, huh.

So instead of one piece. It was meant to be something that you walked into this room and the walls were all painted black and there was writing in white, the poetry was written on the walls in white. And then there was a floor piece that went around the perimeter. That was this DNA strand that spoke about generational trauma.

It was ephemeral. And so when it was destroyed, it was destroyed with prayers for aiding personal family trauma, which we all have. So I was really trying to use art as ritual for the first time in a really direct way.

And then also there was an olfactory element with this resin that I burned at the opening. It’s from the sacred Ceiba tree in Mesoamerica. And so it smells really, it’s like a cousin of frankincense copal. And so you could smell this incense and then you walk through the panels and see people through it, read the poetry and at the very back, there was a healing table, which invited participation from people who came in.

I invited them to do a practice that I do with the imagination, an imagination technique. It’s a healing practice from Mexico, indigenous Mexico, where you put like planing wood, basically, which is crazy because that’s actually what I use for making my installations when I was researching this.

You put it on top of a body, wood shavings or corn kernels, different pigmented earth with prayers and it sort of is this idea of extracting the ailment from the body with prayers and with this material. And then they had a selection of different color wood shavings below the table or corn. And so people were just writing all of this pain on the paper and then putting material on top of it.

To be an ArtsWave Truth and Reconciliation grant recipient this year, and also for the last two years, it’s really meant just a complete transformation of my life and my practice that has fed every part of me and my family. The ripple effect is immeasurable, but it’s really allowed my work to be exemplified and manifested in such a robust way and such a far reaching way without limitations.

It was really a gift that was the perfect timing for me in my life. So it was very cosmically timed I feel like for me. I was able to do further research on these different ruins sites, really reach back into my heritage, have incredible experiences of a lifetime and offer that to my family, my children.

There was a hidden truth that was part of who I was and my heritage and what made me me basically in my own lineage, my own indigenous lineage, because it wasn’t just part of the status quo or the canon or the culture. It was something you have to kind of really, especially to be living in the Midwest, it was something I had to really dig into.

And so the project for me was a way to express that and the support to express that connection to the truth and wisdom of indigenous ways of life, ways of seeing, ways of operating in relationship to the world, to their selves, to myself, you know?

And so I think a lot of marginalized people have struggled to have that kind of strength in who they are and what their history is into an elevated place. It was really a way to honor that truth of who I am that had been shrouded for much of my life.

I’ve noticed that social media culture and healing culture online is very ubiquitous now. And a lot of these are sourcing indigenous practices, you know. As I’m seeing that and, and I’m seeing the communities at large really look to indigenous practices for healing, for healing modalities and implementing these new techniques.

I think it’s important to honor the original holders of this because María Sabina one of the poets, healers that I feature as a inspiration for my show, was one of the Mazatecan healers that got really famous for sharing these mushroom veladas with rock stars from the sixties. And it sort of opened a Pandora’s box where people no longer honored exactly how this humble, powerful woman did it.

And so it caused her to lose everything she had, really. I think her house got burned down. It just completely destroyed the ecosystem of her little village in Oaxaca. And as we’re seeing all of these influencers and people using those modalities of, you know, burning sage and plant medicine, earth medicine journeys, and so on, like, I think there needs to be an honoring of those people who, against prosecution, vilification, exotification for the past 500 years, even torture, like they kept these practices alive, even though it was dangerous for them to do so, and they went underground and did it.

And now, you know, people are doing it. It’s kind of cool and like trendy or and I think it’s really helping people too. But I think part of my show TLACUĀ PAHTIĀ was to invite public participation in some of the artwork, but also to learn more about the Indigenous Medicine Conservation Fund, and to contribute to it, these original people and stewards of this wisdom and knowledge of these healing practices of indigenous medicines all over the world, not even just Mesoamerica need to have a seat at the table when policy and on the cultural level, when people make decisions, you need to be thinking about this idea of reciprocity and honoring the original holders.

That is inherently an indigenous value. I think it’s important to not just say it or to do maybe a superficial like acknowledgement or something. I think we need to have an in-depth look at where these practices are coming from. And also if it isn’t part of your lineage, maybe look into your own lineage because everybody has indigenous people, if you go back enough. In Europe, there’s indigenous people, you know, all over the world.

So just asking these questions and not just accepting things at one level, but asking these questions about our responsibility in using any of these modalities of healing as we’re in this really like palpable period of time of reconciliation. So it’s good. It’s a good time, I think, to be having this introspection and questioning of ourselves individually including myself.

Theme: Just a dream, dream

Gabriel Martinez Rubio: My name is Gabriel Martinez Rubio. I am originally from Mexico. I’m living in Cincinnati since several years ago. I’m so grateful to be part of a Truth and Healing Black and Brown Program Artist from ArtsWave. My piece in this wonderful showcase, it’s called Pato y Muerte. That means duck and death.

It’s a dance theater play. It talk about friendship and life in general. It’s for all audiences, but focus on the kids and I’m so happy to be here. This year I decide to dedicate my project to the kids, so it was divided into parts.

The one part you see on the theater, the first part, it was our workshops. I did our workshops for kids for eight weeks. I call that project Dance and Express Yourself. I did it in both language, in English and Spanish. So it was like baila y expresate. That means that the kids, they made some exercises that can reinforce the self-confidence and they discover different kinds of movement to the overall expression and dance kind of mixed together.

So, I got a 40 kids signed up for this workshop, so of course they went back and forth, sometimes they have the 40 in the dance room, sometimes you have 8, sometimes different ones. The kids like it and their parents like it too. That’s very important.

And the second part of the project, it was this piece, it was called a Pato y Muerte is a story based on a book that is named Duck, Death, and the Tulip with a German author. And I made this kind of twist to the Mexican tradition, the Day of the Dead. And the story is about friendship, loyalty, the seasons of the year, doesn’t mean the cycle. And also is the cycle of the life.

In this story, people can feel kind of like a connected with, first of all, to appreciate that people they love are the people that, who they share the friendship. And the second is the acceptance of loss, right? That some of us, I think, when having a disappoint and it’s very hard to accept that somebody or something is not here with you anymore.

So all these celebration that we have to honor the loved ones, that they’re not here anymore is part of my culture.

Because of that, we have a lot of stories like that. Some of those stories are from the Mexican culture and the Mexican people, I guess, population.

But other stories is not Mexican and we kind of accept it because we feel connected with that, the stories connect people. You can feel like reflected in some of the stories and you can feel that connection as part of you, even though if it’s not that really attached that the culture, right. I hear it for the first time in Mexico and so I thought, oh, I want to do something like with dance piece, with that story.

That’s the way I use this site, this story in there, but the book is very short. It’s like five pages, so I decided to add all these complement in every season change. So they have a story for spring, for summer, for fall, and then for the winter. I was kind of nervous, kind of scared, concerned how people here in the US can take this story, accept this story.

I think the relationship with that, it’s very different, but in general, I, something that people don’t talk too much about, right. But in my culture is all the time. It’s just like, we have that, we have this celebration and we go to the cemetery sometimes and we talk to the people that is not here anymore.

And we say things that we never would able to talk to about. Or sometimes we ask for an advice. Maybe we have this like a mind of thinking that is not real, but that is part of our culture, right? I won’t say that is therapeutic, but it’s, the more you talk about something that is painful or hard for you, I think the better way you have to go on.

Yeah, I think it’s the way that my piece can feel in this, especially after the pandemic with everybody was like confronting themselves and located in their houses, I think we really go to so many things that we never thought about, it’s been confronting yourself sometimes you and your walls because you couldn’t go out, and I discovered that a lot of kids, they lost a lot of relatives.

Sometimes they’d get orphaned because their parents passed during this terrible thing. And so I was kind of like, I’m most focused on that. And maybe this is the time for me to bring this story for kids. Especially if they go through that stuff, they can have better acceptance, or they can see the life in a different way with this cycle that everybody has to go through.

I always think a lot of possibilities. Oh, I can do this, I can do this, I can do this, I can do this. And probably of all these thousands of possibilities, I just have to reduce, reduce, reduce, reduce, and just have three possibilities all the time. This year, I didn’t have, for instance, original music. I’ve been having that before with the other grants. I hire a musician. And ask for a specific use for my pieces.

But this year I decide, for instance, to use popular Latin music. So it’s music that Latin people know very well. So the first part, it was like a different version of Bossa Nova. And the second part, it’s something that we have in Mexico with the piano is called Canto Cardenche with these songs for the very healing and to bring all the sadness out.

But they have this specific version in a piano, which is very nice and mellow. Then we have another piece that is like a cumbia. It’s called Calaverita, which means little, little skull. And the last part is music from Holland.

And the creative process start always for me writing. I don’t have my own space, so I have to rent space. When I go to that space, I have to have everything written down very specific things that I have to work on. And this is the first part, just writing down whatever I need to know. I always have my own script for the dance piece would mean that cycle or emotions or tempos that I need to work with.

And then I find the dancers or the actors that they need to be on this piece. So that means I got the grant in November and I have to have done all that by the beginning of January. After that, I do like a movement research by myself, exploring with the emotions and exploring with the tempos that I need to use.

I really like to put a lot of stuff, like emotional things, like feelings on my pieces. So I have methodology for that, that I’ve been just studying and working on. And how the emotions connect the rhythms, and is that I work for my pieces. Connecting the emotions to the music or to the rhythms, even though it is not music on it.

And then I have my first interview with the artist, so I talk to them about the project. And then we have another meeting and then we read the play together or read the script together. Because for me, it’s very important that the people collaborate with me, they like the project more than other things.

If they like the project, we want to have like a very good match and it’s going to be something nice to work on. I’m the director also of the piece, the choreographer, and the creative part of this. This piece is also made with papier-mâché. In my culture, we have a lot of the crafty stuff with papier-mâché. So that’s what I decide to do all the art with papier-mâché. And so I work on that too.

My truth, I remember when I was a student, a dance student, we started doing like choreographies and that kind of things, I was very scared all the time to talk about myself. I always say like, Oh, I don’t want to talk about myself. I’m just going to create characters and do whatever they have to do.

But I don’t want to talk about, never about me. And then to the past, and I discovered that I’m always talking about sometimes me or sometimes the reality that I see. I was trying to avoid to be very personal, but probably the art is not all that way. I think I always talk about something that is real, even though if it’s just something on the stage, I wouldn’t say fantasy, but it’s a performance.

And probably that is my truth. It’s the way I see the world. The things that I think is important in different moments, I think in this moment for me, it was very important to talk about, after the pandemic, to talk about this acceptance for so many things, for so many loss that we have in life, sometimes, it could be something very close, sometimes not really close, but, or sometimes if somebody lost someone, you can kind of be more like, you can understand the people better, probably, how they go through or how they act in different ways because they have something inside that they probably cannot express, or they cannot, like, heal as fast.

My tool to show the things that I see that is in the real life, sometimes it’s important to talk about, even though it’s painful or we don’t really want it. Being part of the Hispanic community or the Latin community here in Cincinnati, It’s very important for me to be part of this program because I think little by little we are, we are open doors for the people who are behind us.

Deqah Hussein-Wetzel: My name is Deqah Hussein-Wetzel. I am a podcaster, historic preservationist, the co-host and producer of the Urban Roots podcast, the founder and director of Urbanist Media, which is an anti-racist community preservation organization based in Cincinnati, and the recipient of a recent ArtsWave Black and Brown Artist Grant, where I produced the Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal video.

The connection to ArtsWave is actually that it helped fund the first season of the Urban Roots podcast and it allowed me to hire other consultants to work on the project with me so that I was able to have some people who could help with the production components that I was not as familiar with, being that I have a background in preservation and as well as like urban planning and so doing media was different for me and ArtsWave allowed me to kind of get my foot in the door and then in 2021, we won Best Podcast of Cincinnati through Cincinnati Magazine and it’s just grown.

The Urban Roots podcast started in 2020 with the idea of wanting to tell urban histories through the perspective of people in a particular community or city. So the first season was on African American history in Cincinnati and we focused on the communities of Avondale, Evanston, and South Cumminsville.

Interviews that we recorded from the first season, you know, we couldn’t use all of it because our podcast is very narrative documentary storytelling-oriented. So the video allowed for me to put some visual components onto some of the same voices and themes from the first season.

I definitely wanted to branch out from just Cincinnati. So our first season was on Cincinnati and the second season was on African American history in New York and Brooklyn Greenwood Cemetery, as well as we told story of an amazing African American woman who basically founded Black LA, Biddy Mason.

And we also told Madam C.J. Walker’s story through the lens of Indianapolis, and in order for people to really understand how history has transformed the built environment and people’s cultural experiences, looking at it from different places, it’s just, in my mind, the best way to give people a larger perspective.

That was definitely why Urban Roots season two and even three and such, we didn’t want to silo ourselves and just focus on Cincinnati. Not to say that we don’t have intentions to because part of the work that I do with the Urban Roots podcast is that I started a non-profit called Urbanist Media and in that non-profit it’s a community preservation collaborative.

And we have a really great group that has become part of our organization called Queens of Queen City, and they are like an established group of historians who focus on women and LGBTQ+ histories, and their work is so powerful in Cincinnati, and I’ve always thought, you know, Urban Roots podcast being the first season in Cincinnati, I never wanted to forget about, you know, the communities here. I want to come back to it. And I want to come back to these stories.

So I think through Queens of Queen City, we are working to develop that path forward to focus on Cincinnati. But in terms of this particular project, the video bringing the audio components from the first season and layering some archival photos as well as aerial photos.

So I had to do like a whole bunch of research to find ODOT, so Ohio Department of Transportation aerial photos from like the 50s and like before the highway came through. And then I also had a friend of mine who was a consultant on this project, Mark Stucker. So Mark Stucker is a drone photographer locally here in Cincinnati. And we went to each of these communities, Avondale, South Cumminsville, and Evanston, and, you know, spent hours doing drone shots. And then having to find a way to weave that through into the video. And with the help of story editor, Vanessa Quirk and production editor, Connor Lynch, Connor is pretty integral in helping me make sure that the video is a super great production quality and with video was really helpful. And both Connor and Vanessa are actually my counterparts with Urban Roots Podcast.

All of that kind of comes together, and we’ve been able to make a pretty awesome video, I think. And the title, Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal, was from a James Baldwin quote, and it basically reflects back to the fact that in the mid century 1960s, it’s pretty much, 50s, 60s, was the height of the movement to construct highways throughout America.

It destroyed so many communities in the social aspect. And I think the purpose of the film is to help the general public understand like what urban renewal means in general. And that’s really the purpose of the film is to explain, not so much from like the white people’s perspective though, but like from the communities that are impacted, right? The marginalized folks, the Black folks in particular.

And it happened all across the country, and that’s why I find value in talking about different cities throughout our podcast. Urban renewal was so transformative in a not so great way across the United States. And I think just having a little bit of Cincinnati focus helps at least the people locally see how the highways had impacted the marginalized communities.

And we talk about that in our first season. And there’s a video that was part of the showcase for ArtsWave that we put out that was for the purposes of explaining the West End story. But I’ve always felt that there are other neighborhoods that we don’t hear a lot about. Evanston, Avondale, South Cumminsville, some of them, as well as Walnut Hills and Madisonville.

And for example, Madisonville and Walnut Hills have extensive rich African American history that is just like so integral to our city. So I think it’s all about like who shapes, you know, our city and, and how our city is shaped by people. And the fact of the matter is that if you think about it today and like how development happens, it usually happens because I feel that cities and just officials aren’t thinking so much about the history, and like what had happened.

Because ultimately they’re just creating similar situations again. Gentrification is an example of how that happens today. I think the purpose of everything that I do is in a way to prevent further erasure of both the culture, society, the built environment. And as a historic preservationist, we do usually focus on the built environment, but that’s why I’m trying to bring the storytelling aspect into podcasting and preservation in this, like, very new way.

Like, I think our podcasts kind of resemble This American Life and 99% Invisible in the type of storytelling we do, but it’s just so focused on urbanism in the history of people who’ve not been heard. I’m an African American Woman, and I consider myself a preservationist and I live in a world where yes, they’re filled with a lot of people that don’t look like me. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t find paths forward to helping underrepresented communities reconcile or reclaim really their history.

I think preservation can uplift communities in a number of ways, but I think probably the most controversial is the development component of it. I just see such a lack of community conversations when it comes to the development that does happen in an area. What do the people in the community really value in terms of their history?

And I wonder if just having conversations to hear people out more is like what needs to happen, whether that’s at the community level, the city council level, the development level. Is there a place for that feeling of connectedness to that property to come back? It’s not my truth, but it’s the truth of the people that I spoke to and interviewed: Tim Kennedy, Andy Williams, Mary Ward, Mr. Stallworth, even Vice-Mayor Jan-Michele Lemon-Kearney, who’s lived in Avondale, like all her life.

So hearing what people have to say about the past, stores, the businesses they remember, the parks they remember, or at least even just hearing that they felt that their community was connected and then a highway came through and they didn’t feel it was connected. That truth, that’s what I’m trying to hear.

Listen to the Urban Roots podcast. Just listen to five minutes of it and if you feel that it moves you, keep listening. But I think it’s a really important resource for people in the communities that I’ve worked in. Those people have come to me and said, I was really moved by the season, the first season in Cincinnati and Avondale. People came to me saying that they’ve cried when they were listening to it, and they lived in that community all their life.

It’s not just about the audience, the public like listening and everybody trying to hear. I think what the Urban Roots podcast has to offer can be really transformative if people just listened.

In an ideal world, I would love for urban planning to truly involve community engagement. So I went to school for planning. My undergrad’s in planning, my master’s in historic preservation. And I’m about to go for a PhD in historic preservation, and I’ll be at Columbia. So, you know, I’m excited to have this opportunity to really dive deep and understand kind of the nuance here.

But the hope is that we can and we as in like society be more equitable in the way that we do development and I think that becomes like layers of community engagement that are done in a different way than they have been done before.

The approach isn’t really working. Being Black in America’s hard, it’s like really really really it, like being any person of color, being a woman, like I was at the place where it’s like all right, I gotta figure out how to do something about this, like.

And so yeah, that’s kind of my hope is to keep diving in and seeing just how much more we can transform to make cities think about not development first, but people first.

And then also figuring out how to make it about thinking about the tangible as well. Cause like the storytelling and that component is really, really important, but in places where there’s been erasure, how do you bring back the history? How do you help people reclaim lands that were once their homes or their family homes? Yeah, so I think all those things are just like super, super important and what I want to double down on.

K.A. Simpson: My name is K.A. Simpson. I am the host and author of FLIPd, the podcast, a podcast about historic Cincinnati places and spaces told one week at a time. The podcast and intention behind the series is to kind of flip the narrative of what we know as history in Cincinnati and put African American faces in front of those narratives.

So kind of looking at a lot of historic spaces and places like Union Terminal, the Taft Museum of Art, the William Howard Taft site, Devou Park in Northern Kentucky, looking at those historic spaces and talking about the African American narratives that went in and around those historic spaces and places.

I’m a closet historian, so I like history just a little bit. And that was inspired by my mother who, when I was a kid, she would tell me these stories about these spaces that we would travel around and they always centered around African American spaces, but I never heard about those. I never read about those outside of my family. So I wanted to bring those stories and actually look into those stories and bring those stories to life.

One of the things that means the most to me as being a grant recipient from ArtsWave for the Truth and Healing grant is that I’m being recognized for what I do as an artist. I think in the past, it’s been harder as an African American artist or author to get your stories to the forefront.

And I think this Truth and Healing grant actually elevates that artistry and hopefully preserves it for the future to come. You start to hear these unknown stories, and when you hear these unknown stories, whether you’re Black, white, wherever you’re from, you hear those stories, and it gives you a greater understanding of the past. So, for a couple of things, that you don’t repeat the past, and also to help you move forward, to make better decisions on how you interact with spaces and places and people for that matter.

Through the podcast, I’ve actually learned a lot of things that I did not know about Cincinnati, and that’s what’s fun, right? It’s trying to deliberately look at or find African American stories in these spaces and places.

One of the bigger things that I’ve found out was on one of my first episodes talking about Northern Kentucky’s Devou Park and how the family started out as a milliner in downtown Cincinnati, so a hat maker. And then they went into real estate development, so landlords in the West End in the early 1900s. And that started to pique my interest. I was like, wait a minute, there were Black folk that lived in the West End during the same time. So kind of finding that, that was just something that sparked my interest.

Being from Northern Kentucky, being from Covington, Devou Park has always been this kind of special place, a great space. And it really is, but it’s just interesting to find that little fork [???] it was like, Oh, some of the money that was made to buy a property of the Devou Park was because of the backs of African Americans in the West End.

We had a lot of things to explore during COVID and podcasting was one of those, and I fell in love with several investigated episodic podcasts. And I thought it would be a great forum to kind of expand my artistry.

In general, my creative process is that I get all the information that I can and I formulate a story in my head. Most of that story is dictated by how I want to find out the story and how I actually discovered a lot of the things.

And so with podcasting, that’s the process with writing depends on what I’m writing. It’s usually if I’m writing a novel, I just start throwing ideas down on the page and seeing what sticks. And then again, kind of going back to say, well, how do I want to see this story unfold?

Sometimes I start at the beginning. Sometimes I start with an idea of how I want it to end. And I think that’s what makes it exciting about being an author for me is that my process is varied. And each new piece brings a new, exciting kind of journey to take.

I started my career in libraries, and I was going to be a librarian at one time, could you imagine? So, kind of doing that research and using the tools that I’ve learned over the past two decades of kind of investigating and working in kind of that library space to find things that people don’t realize. So, like, there’s still microfilm and microfiche. They are great tools and resources to use and I was reintroduced to those during my FLIPd journey.

There’s roughly about seven episodes per season. We’ll be recording episode five today. I’m super excited about that. But I’d like to expand right now. It’s kind of more Cincinnati-centric.

I’d like to expand that to Northern Kentucky. I’m a Northern Kentucky boy. So I’d like to expand it to Northern Kentucky as well for the second season. Not to say there aren’t any spaces and places in Northern Kentucky that’s going to be in this season as well. So I don’t want to limit it. There might be 40 seasons. There might be two.

So, one of the things that I would like a kind of international and national listeners to know about Cincinnati is that it’s very unique space in the United States for a couple of different reasons, not only geographical, but also kind of Metro-wise. I’ve been in the military, I’ve lived in different spaces in the United States and I always come back not only because of family, but because of the topography, the geography.

One thing that I would like people to know and it’s kind of quirky that when you fly into Cincinnati, you’re actually flying into Northern Kentucky. So if people say, well, I flew through Ohio one time in Cincinnati, it’s like, not really. You actually never set foot in Ohio. You were always in Northern Kentucky. I think that would be what I would want people to take away.

Coming up in the episodes, we’re going to be looking at the Cox Mansion, which is now the Clifton branch of the Cincinnati Public Library, which used to be a home and I used to actually live in this house. Long story, you’re going to hear why I was living in that house now that it’s a library in the podcast.

I’ll also be looking at Taft Historical Site as well. In addition, I’m going to move over to Northern Kentucky and bring kind of the backstory about Margaret Garner, who was a formerly enslaved individual in the 1850s. Also, little known fact in Northern Kentucky, there was a huge racetrack, a horse racing industry in Northern Kentucky. So I’ll be talking about that as well.

My truth is bringing my story alive and my family’s story alive in Cincinnati. My great grandmother came to a house in Newport in 1907, lived on the same street until the 80s. So my family grew up on Saratoga Street in Newport, Kentucky. I’ve traced my family back over a hundred years within one mile of the Freedom Center.

So to elevate my family story and people that look like me, I think that’s one of the great things that is being brought about with this truth and healing process.

Desirae Hosley: Hi, I’m Desirae Hosley, also known as The Silent Poet. My project was Social Therapy: Are We Healing? for ArtsWave. Social Therapy was started back in 2020, and we kind of had the conversation of, how are we healing as artists since 2020? How do we rebuild everything that’s happened? And so Social Therapy was that pinpoint of understanding how we could grow together as artists, as well as showcase what we’ve been through and how we are starting to come out of what we’ve been through.

So I was able to create a platform where we can have conversations and dialogue as well as have writings and how music and poetry and art all collide together as one. So Social Therapy started as a writing workshop that has grown since as a full blown conversational project.

So we started with having this group of panelists come together and have conversations about how are we healing as artists, especially in this decade and thinking about the pandemic along with being a Black and brown artist and the whole Black Lives Matter movement and how it can be centered around everything that’s happened since 2020.

Social Therapy actually opened the door at first because of the youth. And it was a way to bridge the gap between youth and adults and how no matter at what age you are at, we are all going through the same situations together. And we all need to find ways to cope and build with one another.

“Are we healing?” was the main theme this year because I wanted to focus on how are we coming out of the pandemic? How are we rebuilding? What does it look like? How does it feel? And when it is poetry, there is a way of healing in that poetry. When it is art, there is a way to heal in that art. When it’s music, there is a way to heal with the music and that makes us all come together as one.

I picked artists through ArtsWave. I picked some artists that have participated with me and some artists who have been with me since Social Therapy has started. And we kind of thought of questions, myself and I had a partner with me who kind of helped me go through the conversational piece of it, how to have these conversations without anyone feeling unsafe.

And one thing about Social Therapy is that it’s a safe space. I want to honor those around me to feel comfortable to have very open dialogue when it centers about their own mental health and what that feels like for themselves. And I wanted to make sure that I held it precious in a very precious form.

So when I had the conversation at the coffee shop and for even the coffee shop to offer drinks that were healing to come along with the conversation, and to create a space where not only are we not interrupting each other while we’re having a conversation, I provided notebooks so that if people had questions, they could hold those conversations towards the end and not forget what they were thinking, because I know sometimes when you’re like listening to someone, you’re like, Oh, I have a question I want to ask you now.

But people were able to hold those thoughts and wait to the end after the panelists were done having those conversations. I separated them between women and men. So I had the women panelists have a musician come in that was a male that shows support that men and women can have each other’s back, no matter what we’re going through.

And then when I had the alt panel with all men, I had some young ladies that were used from Aiken High School and their teacher that came along as well to hold that space. And hold conversations and ask questions along the way about how can we all heal, especially for the youth? Because that was one of the bigger questions that came out of this, are we healing?

It was like, how do we start to heal the youth? Because the youth also wants to be healed. And Social Therapy was able to hold that platform and create that safe space for them.

I came up with these cards and no one was like, what is the card? So I came up with this card that described Social Therapy like are we healing because and like what is your reasoning?

And it actually started with a poem for myself I was reading a book about why am I healing and I was like, why am I healing? And I started to think about my daughter. That’s one of the reasons why I’m healing I’m healing because I have to live every day, right? I have to go outside and face the world.

And sometimes it’s difficult. Sometimes it’s hard. And most of the responses were in that same realm. People felt like I’m healing because I have to get through the day. I’m healing because I want to just feel good. I want to feel good. I want to present myself looking good. I want to be happy. It’s my choice to heal.

I’m healing because it’s not going to end at the end of the day. Like, we will continue to try to build and grow as a human and it’s hard some days, but we’re going to continue to keep ourselves striving forward and beyond and know that it’s not the end that we could continue to keep pushing. So those cards were like, really effective and people were able to like, pull themselves out of whatever they were going through at that time and think like, Oh, my God, I’m healing because of life. Like I want to be here. I want to be happy.

For me, it was a reminder for a lot of the audience members to kind of think about the reasoning of healing and why it is important and they were able to capture those moments in those cards.

The poem came first. When I thought of the idea about are we healing, I told Michael Coppage, like he was part of that thought process, because I went to one of his events, and looking at his art, I was captivated, but I also was thinking to myself, how are we healing as one?

When it comes to people being arrested, we see the same video, social media. It’s like this constant reminder of the things that we’ve been through in our past. How are we pulling ourselves out of that? How do you begin to see joy? And so the poem itself was like, okay, I want to see joy for myself. How do I get other artists to find joy?

Why do we have to continue to write the same things that’s about the horrible aspects of life. Why can’t we build about what joy looks like after everything that has happened in our lives. The way I celebrate my birthday, I celebrate it as if it’s a new year. I don’t count the new year as my new year.

I count my birthday as the new year. And I started to think about those aspects of like, for me, that’s joy. September is joyous to me because it’s my birthday month. I celebrate the whole month. I don’t celebrate a day. I feel selfish. And that’s the only time I get to be selfish and I want others to begin to think in that way to have that those moments where you can be selfish for you.

You don’t always have to be selfless. You don’t always have to put everyone before yourself. And I understand what that means because that’s my life. And that’s what Social Therapy means for me. Social Therapy was built off of others. For hearing other people’s stories. I enjoy listening to people in their stories and building from those stories and trying to see how we can all learn from each other because no one, like you’re not alone in your story, there’s someone else with the same exact story or going through something that is similar.

And these stories can be shared all around. And that’s where Social Therapy: Are We Healing or the panelists and having these conversations and dialogue comes from was me literally having conversations, sitting, drinking a glass of wine with someone and saying, how do you feel?

Before I even had the event with the panelists, I had conversations separately, one on one with each panelist beforehand and ask them how comfortable they felt with having these conversations about themselves in front of people. And for many, it was, this is like a cleanse. I’ve never got a chance to share this part of my life as I’m able to share this with everybody in hindsight, in front of a group of people I don’t even know, and yet they will accept me and everyone will understand, no one’s here to judge you.

And so when I thought about Social Therapy as a whole, when I created the video, that was the main goal. The goal was to let people know that we are not here to judge you. We are here to love each other. I am here to love you. I am here to hold space for you, and I see you and I hear you. And that’s what we’re here for.

This is my second year as a grant recipient. I took a break last year and then I was like, Oh, I’m gonna apply this year. It’s an honor. Like, it truly is an honor to be a recipient and to be in the same space as all 18 artists and to get to learn from these artists as well.

Not only was it Michael Coppage that I had a conversation with, but Michael Thompson was on my panel. And Camille Jones, who was a part of (CA)^2 dance team and being able to really sit with people like for warmth and to actually have conversations along the way and see like, what are you doing? How are you going to do your video? How are you going to shape what you got going on for ArtsWave? And we were able to really collaborate together as a whole and share our gifts with each other and have conversations about how this has truly grown since the very beginning.

ArtsWave has opened a door for individual artists that many grant recipients like you can’t get, you know. ArtsWave has opened that door because you have to be with a physical group or a team. You could be an individual in this moment and share your gifts openly, which is very awesome because, like I said, there is no other place where you could be an individual artist and get grant money to elevate what you already have going on.

So I’m beyond grateful for them holding the space and also just being able to receive one of the grants. The truth that I expressed is transparency. I was able to be very transparent in this process, not only about my healing, but about my story as an artist.

I started doing poetry 17 years ago at UC, getting on an open mic and letting people know that I was fat. And that has helped me with public speaking and has helped me share the story of me being a single mother.

It has helped me really understand that I am who I am and no one can take that away from me. That’s my truth. And I stand by it.

If you can remember one thing from this conversation, from just me being a part of Truth and Healing, it would be joy. Social Therapy is all about joy.

Why I heal. I am healing because I want to breathe unapologetically. I am healing because I need to embrace love again. I am healing because I deserve to be loved. I am healing because I feel that I am not worthy of taking up space. I am healing because I see the piece of me that is ready to shine bright.

I am healing because I love myself way too much to hold back. I am healing because my daughter is watching. I am healing because I am tired of feeling that I am not good enough. I am healing because I can grow from my past. I am healing because I choose peace of mine.

Helen Todd: Thank you for spending some time with us today. We’re just getting started and would love your support. Subscribe to Creativity Squared on your preferred podcast platform and leave a review. It really helps and I’d love to hear your feedback. What topics are you thinking about and want to dive into more?

I invite you to visit creativitysquared.com to let me know. And while you’re there, be sure to sign up for our free weekly newsletter so you can easily stay on top of all the latest news at the intersection of AI and creativity.

Because it’s so important to support artists, 10% of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized nonprofit that supports over a hundred arts organizations. Become a premium newsletter subscriber, or leave a tip on the website to support this project and ArtsWave and premium newsletter subscribers will receive NFTs of episode cover art, and more extras to say thank you for helping bring my dream to life.

And a big, big thank you to everyone who’s offered their time, energy, and encouragement and support so far. I really appreciate it from the bottom of my heart.

This show is produced and made possible by the team at Play Audio Agency. Until next week, keep creating

Theme: Just a dream, dream, AI, AI, AI