The A.I. Dilemma

It’s becoming clearer and clearer that A.I. is a bullet train with no operator.

If you think that the pace of development in the space is hard to keep up with in the news, don’t feel alone. Even leaders of A.I. companies have expressed the same sentiment.

It really feels like almost every week there is a significant release of a powerful new model, and some research is already on the cusp of being able to interpret our dreams.

Quicker than we could’ve imagined, A.I. is already doing more of the things that we fantasized about it being able to do for us someday in the future. As A.I. meets more of our needs, it becomes more entangled in our lives. As more people start to see the enormous paradigm shift brought by A.I., it’s worth revisiting The A.I. Dilemma. It’s a crucial message, produced by the duo behind The Social Media Dilemma, to alert the public about the profound implications of A.I. for the social order as we know it. Their aim is for us to not repeat the same mistakes tat we made when it comes to social media in regard to having a disruptive technology become too entangled in society with massive unintended consequences and without adequate regulation.

3 Rules of New Technology

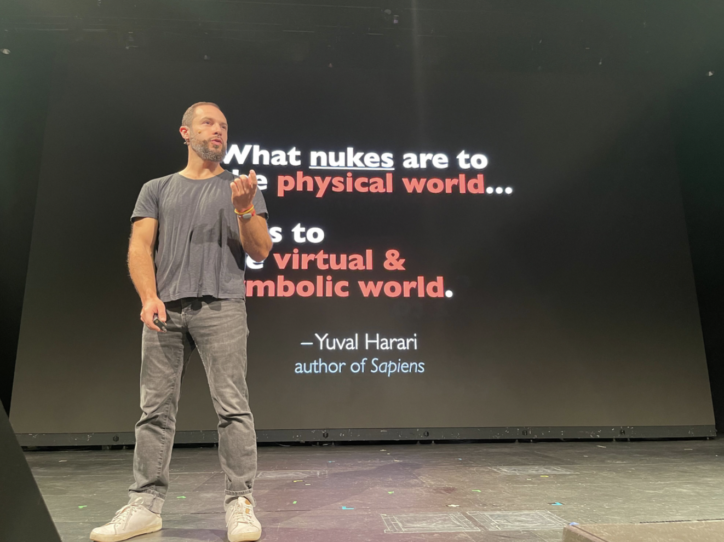

Created and presented by the co-founders of the Center for Humane Technology, Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin, the presentation’s central premise is that A.I. is advancing exponentially faster than anyone can predict and that this technology in its most powerful form is available before society can even conceptualize the issues associated with it.

The dilemma breaks down further according to three rules of new technology that we’ve seen play out in the past, notably with social media, and that we’re seeing play out now.

Rule one states that whenever a powerful new technology is invented, a new class of responsibilities will be uncovered. A.I. technology can interpret the presence and pose of humans in a room just by analyzing how wi-fi signals travel around them. There are deepfakes, voice cloning, and a long list of vulnerabilities that were not so easily exploited before artificial intelligence. All this technology exists right now. Yet lawmakers and institutions are only starting to think about planning to regulate it.

Rule two states that if a technology confers power, it will start a race. The nuclear arms race is a classic example, but there are countless others. Look no further than social media. The social media company that can engineer the greatest amount of engagement from its users is the most powerful, like a “race to the bottom of the brain stem,” as Aza calls it. The race is certainly on for A.I. too — it only took two months for OpenAI’s ChatGPT to reach 100 million users. The same feat took two and half years for Instagram.

Rule three builds on rule two, stating that if the race to build more powerful technology is not coordinated, it will end in tragedy. To continue the example, coordination at the highest levels is what has averted total nuclear destruction of the world. But A.I. is not quarantined in a secret government lab, it’s already in the wild and being released by companies in competition with each other. The takeaway from rule three is that no single actor can stop the race.

Now, even though we’ve not really addressed the fundamental harms of the social media engagement-driven economy and what that’s done to our society, we are rapidly adopting new technology that has the potential to infiltrate and disrupt our ways of living to a much greater degree. This should give everyone pause.

Why is Everything Happening so Quickly?

The short answer: transformers. Not the autobots and decepticons, but the common term for the 2017 breakthrough in machine learning that enables all of the progress we see today. The revelation that came along with transformers, according to Aza, is that everything is language. Data, computer code, image pixels, DNA, wi-fi signals, speech, voice — it’s all language in the context of training an A.I. to recognize patterns and generate predictions on what should come next.

That means that, instead of different teams separately making incremental progress on generative text, or text-to-image, or text-to-audio, or generating images from brain waves, all advancements in A.I. converge as language and expedite further development across categories that were once siloed.

It’s not only humans though; A.I. has the capability to test itself to improve. Aza and Tristan discuss the “theory of mind” possessed by ChatGPT. They describe theory of mind as the ability to read the spoken and unspoken intentions of others and use that to adjust your own response, like the conceptual precursor to strategization. It took some years for ChatGPT to advance from a three-year-old’s theory of mind to that of a nine-year-old, but only a matter of months after that to exceed the average adult’s theory of mind. This A.I. capability was only discovered earlier in 2023.

The learning rate of A.I. is often described as an exponential curve. Visualize a line on a graph increasing gradually at first before reaching a certain point on the x-axis where it shoots up like a rocket ship. One of the most vexing aspects of A.I. is that nobody knows where that point of takeoff will be, until it happens. In a survey cited by Tristan and Aza, even the experts working with A.I. and exponential curves overestimated the time it would take for A.I. to be able to solve competition-level mathematics by three years. It took less than a year after the survey was taken for A.I. to handle math at that level, so A.I. is advancing faster than experts predict.

Just as importantly, nobody really knows how or why A.I. suddenly gains new knowledge or skills that it wasn’t specifically trained on. Tristan and Aza share a quote from SVP of Google AI, Jeff Dean, who said, “Although there are dozens of examples of emergent abilities, there are currently few compelling explanations for why such capabilities emerge.”

Let that sink in: some of the biggest companies in the world are shipping products that they don’t even pretend to fully understand, out to hundreds of millions of people.

Who is Regulating Artificial Intelligence?

Right now? Nobody.

At least, not in the comprehensive or deterministic way that nuclear fission is regulated. Tristan and Aza remind us throughout the presentation that we still have not fully grappled with the ways that social media’s engagement economy has distorted our reality, e.g. addiction, polarization, and the breakdown of democracy. Now, that paradigm is so baked into our reality that it’s much harder to regulate against many of the social ills that we all recognize.

They say that we are standing, right now, at the major inflection point for artificial intelligence. However, the duo argue that we are poorly equipped to deal with the gravity of widespread, powerful artificial intelligence. The European Union, Australia, and some U.S. states have taken steps toward codifying barriers around A.I., but it’s an uncoordinated regulatory patchwork right now, and more needs to be done.

The Power of Art

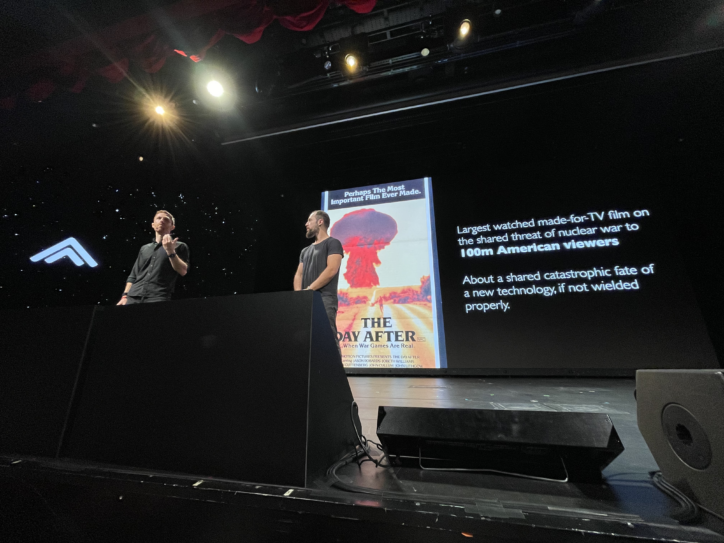

Referring to the Cold War-era PSA film, The Day After, Tristan and Aza say that their goal is to help educate an informed culture, which can collectivize to update our antiquated institutions to withstand the massive disruptions that A.I. will bring. The world needs more A.I. safety researchers, voices of caution, informed interrogators of emerging technology, and most of all, more time to reckon with A.I. and its role in a future we all want to live in. Art can help change this trajectory.

The Day After, which was screened on television both in the U.S. and later in Russia, leveraged art to help the public understand the consequences of an uncoordinated nuclear arms race. Watched by over 100 million people around the world (it still holds the record for the highest-rated TV movie in history), the critical piece of art transcended borders, languages, and politics. The film helped influence not only public opinion about the threat of nuclear war, but also policy. U.S. President Ronald Reagan watched the film more than a month before its screening on Columbus Day, October 10, 1983. He wrote in his diary that the film was “very effective and left me greatly depressed” and that it changed his mind on the prevailing policy on a “nuclear war”.

This is another moment in history where art can bridge the gap between whatever conceptions the general public may have toward A.I. and the consequences of complacency.

Tristan and Aza say that’s why they spend so much time traveling to talk to audiences of creatives, leaders, and entrepreneurs. Our information ecosystem may be more splintered than it was in 1983, when The Day After was released, but we’re more connected than ever and art – whether its music, movies, mosaics, or memes – can still inspire us to meet the moment.

Tristan and Aza like to close out with a simple request that’s worth emphasizing to artists:

“The world needs your help.”

Let’s see photos, paintings, dances, films, reels, and art of all forms that shows us the world we want to live in, and the one we want to avoid.