Ep42. Interrogate A.I. with Art: Explore A.I.’s Impact on Culture and Society with Marlies Wirth, Curator for Digital Culture and Head of the Design Collection at the MAK — Museum of Applied Arts

Discover thought-provoking exhibits that interrogate technology through art with Marlies Wirth, the Curator for Digital Culture and Head of the Design Collection at the MAK — Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, Austria.

Marlies’s unique role is to keep her finger on the pulse of emerging transformative technology and commission artworks that interpret tech’s cultural, social, ecological, and political impacts. In collaboration with artists and institutions around the world (and, you could say, in other worlds), she brings together critical reflections on our present and visions of our future as they’re shaped by technology.

“It’s so interesting how culture changes through technology… especially to see it through the eyes of artists, designers, and architects who have been deeply concerned with these topics.”

Marlies Wirth

Marlies is also a frequent participant in international lectures, talks, and juries on art, design, and digitalization. In addition to her institutional work, she develops independent exhibition projects with international artists and writes essays and texts for publications.

Some of her many notable exhibitions include “Artificial Tears,” “Hello, Robot. Design between Human and Machine,” “Uncanny Values. Artificial Intelligence & You,” “Pardon Our Dust.”

Helen and Marlies discuss the challenging questions that inspire these works, such as what makes us human, what we can gain and lose from integrating with machines, and how identity translates into the virtual world.

Don’t miss this episode’s discussions about how a disembodied online avatar challenges our ideas about identity, how we manage ownership of shared virtual spaces, and how Chelsea Manning’s DNA relates to bias in A.I. training datasets.

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2017

© MAK/Aslan Kudrnofsky

Aleksandra Domanović, Things to Come, 2014

UV flatbed print on polyester foil, 7 panels à 5 parts; Unique

Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin

Cry If You’re Human

Artificial intelligence has inspired a recent reckoning with the idea of machines automating our lives – and livelihoods, but that conundrum’s been on the minds of Marlies and her collaborators since 2017.

Her department started to work with artists for “Hello, Robot. Design between Human and Machine,” an exhibit interpreting our increasingly robotic and automated world, and wanted to explore the other side of the coin.

“Our bodies and minds are such a great system, even more intricate than any technology. So I wanted to look at the question, what can and cannot be automated?”

Marlies Wirth

The result of their curiosity became “ARTIFICIAL TEARS. Singularity & Humanness,” hosted by the MAK and featuring installations from over a dozen multidisciplinary artists.

Marlies says the inspiration for the exhibition theme came to her through research on tears. It turns out that tears are just as complex as the emotions that cause them. A tear shed out of pain, for example, contains natural painkiller chemicals, and emotional tears (or “psychic tears”) contain anti-stress hormones to help calm you down. For adults, crying is often also a physical effort, which eventually calms you down by exhausting you.

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2017

© MAK/Aslan Kudrnofsky

Sean Raspet, Ester Grid, 2015

16 artifical flavor components

Courtesy of the artist and New Gallery, Paris

Kiki Smith, Untitled, 1992/93

12-part installation, receptacles made of mirrored glass, pedestal

MAK GK 105

While artificial tears can be helpful if you have dry eyes or smoked a sneaky joint, they don’t replace the benefits of a good old-fashioned sob session. Fake tears are a metaphor for the uniquely human things that cannot be automated or outsourced to modern technology precisely because they are so human.

The exhibition featured diverse works, such as Sean Raspet’s collection of 16 artificial scents and flavors, and other works exploring uniquely natural traits such as human instinct and the role of microbes – other species – living inside our gut microbiome.

“ARTIFICIAL TEARS” (the exhibition) considers these symptoms of humanness in the context of “singularity,” a term coined by Ray Kurzweil referring to a theoretical point in the future when humans take control of our evolution by integrating our biology with machines.

It’s anyone’s guess whether humans and machines will ever integrate to such an extent, but the real questions that “ARTIFICIAL TEARS” asks us to consider are about what we bring to that integration, what we risk losing to machine automation, and what we hold so dear that we can’t risk automating.

What’s on your list?

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2022

© kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

Avatars, Identity-Bending, and Ownership in Shared Virtual Spaces

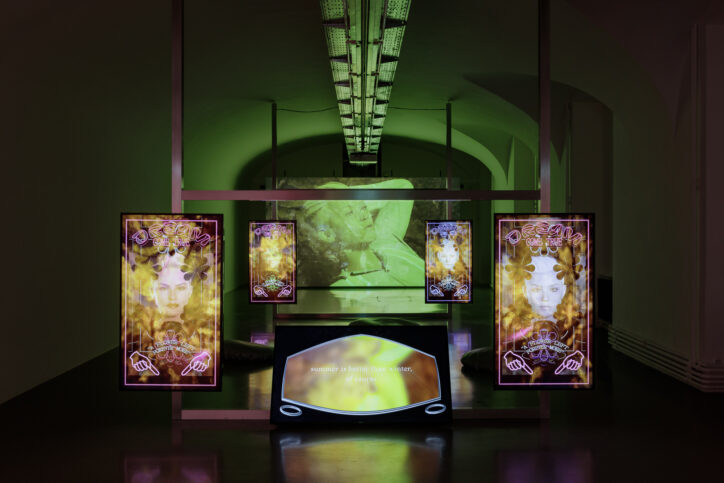

LaTurbo Avedon (they/them) is a digital avatar, curator, and artist who headlined an exhibition Marlies curated in 2022 called “Pardon Our Dust,” which explored the idea of public common spaces in virtual realities owned by private corporations.

“Born” circa 2008 in the proto-metaverse computer game “Second Life,” LaTurbo Avedon’s work has appeared in the Whitney Museum of Art and other galleries, as well as in activations such as the Manchester International Festival. Their work has also featured in games such as the popular online shooter “Fortnite” and others.

You may be wondering, what exactly is LaTurbo Avedon, or who’s actually behind the curtain? That’s the point. LaTurbo Avedon themself is an artistic project about fluid identity in virtual space. It might be one very private person or a team pulling the levers, but without any way to know for sure, you’re forced to ask yourself why their identity matters, or if it matters.

As A.I. makes it easier to digitally clone yourself, at the same time that the metaverse and virtual worlds gain popularity, identity is less concrete than it’s ever been. Online personas are nothing new, but it’s hard to get people to call you by your screen name IRL and character outfits just don’t get the same reaction on the streets that they do on the servers.

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2022

© kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

Increasingly though, new virtual and augmented reality hardware is expanding what’s possible in the digital realm. Those with insecurities about their physical body or bodies that don’t match their gender can choose to spend more time than ever in the identity that they create rather than the one they were were assigned.

Yet, in “Pardon Our Dust,” LaTurbo Avedon challenges us to think critically about what we might sacrifice by forsaking the physical for virtual. Their installation leads the participant through a narration and virtual simulation of abandoned digital landscapes in various stages of construction and deconstruction. Playing on “Pardon Our Dust,” a reference to early 2000’s websites under construction, LaTurbo Avedon’s piece contemplates the next generation of the internet – Web3 – and the alleged decentralization of digital environments promised by the crypto community.

“It’s like properties on the seaside, there’s hardly any space left where you can just go and enjoy what is actually a common good. If you privatize every website, every space there is, how can creativity thrive?”

Marlies Wirth

Some of the virtual spaces we’re starting to see seem like digital utopias, but if you ask Marlies, a utopia is just a dystopia in disguise. Much like the protagonists of culture’s most infamous “utopia” fantasies, she wonders whether creative and expressive freedom is truly possible in commercialized virtual spaces.

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2019

© Process – Studio for Art and Design

Process – Studio for Art and Design, AImoji, 2019

AI generated emoji using a DCGAN for deep learning

The Uncanny Valley: Human Likeness Refracted Through Tech

The uncanny valley is a design hypothesis from a Japanese roboticist who observed that humans seem more fond of objects that look more like us, but only up to a certain point where the resemblance starts feeling eerie. Marlies calls it a “dent in our trust” caused by anything designed to mimic us, from a mask to an LLM. The uncanny valley comes up in the context of future A.I. and the hypothetical day where A.I.-powered interfaces become indistinguishable from human interaction.

In 2019, Marlies and media theorist Paul Feigelfeld played on this concept in their exhibition, “Uncanny Values.”

“It’s such an interesting concept of how humans try to convey a very complex thing that is body language and emotional display during conversation, and sometimes more successfully than other times in these emojis.”

Marlies Writh

As part of the exhibit, a collection of unique A.I. emojis, or AImojis, were developed by feeding a dataset of existing emojis through an early A.I. model and asking it to generate new ones. This was done in collaboration with Process Studio, whose co-founders Martin Grödl and Moritz Resl were guests on Creativity Squared in Episode 32 titled Are Machines Creative?

The results were “rather disturbing” in Marlies’ words, but the AImojis developed an audience and are available in the app stores for download. The AImojis are open for interpretation, but if nothing else they show the unintended consequences of asking A.I. to draw its own conclusions from our collective data without the full context.

“Uncanny Values” includes three pieces about bias in A.I. training data, inspired by the idea that our human understanding of ethics and morals can be uncanny when it devalues humanity and justifies injustice. Throughout history, those different understandings have led to catastrophes and advancements that A.I. knows about but may not have the social context to fully grasp, especially when it has to make decisions. We see the effects of what Marlies calls “corrupted human data” in algorithms that disproportionately identify people of color as crime suspects, or in stereotype-based advertising.

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2019

© MAK/Kristina Wissik

Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea E. Manning, Probably Chelsea, 2017

Installation, 30 portraits designed using custom software that analyzed samples of Chelsea Manning’s DNA

Courtesy of the artists and Iliya Fridman Gallery New York

The exhibit’s entry piece explored this bias through biology, appearance, and gender in Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s “Radical Love: Chelsea Manning.” The installation features a collection of images of similar-looking faces based on the DNA of Chelsea Manning, the former soldier who spent seven years in jail for leaking military documents.

Using an A.I. tool trained on the DNA and corresponding faces of thousands of people, Dewey-Hagborg prompted the model to generate multiple permutations of what Manning might look like based on her DNA. Of course, none of the images managed to capture the real Manning, who underwent gender confirmation surgery in 2018. Somehow, even with all of the genetic information you’d need to build Manning from scratch, the A.I. loses something in translation that renders the output uncanny, close but not quite right. However, Marlies reminds us, it proves that the idea is possible. Undoubtedly somebody is going through a lot of artificial tears trying to span that uncanny valley.

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2023

© kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

Lee Pivnik, Symbiotic House, since 2022

Installation, Midjourney Images, Video 9:00 min., magazines

Leah Wulfman, My Mid Journey Trash Pile. 2022

Installation, Midjourney Images, oil paintings

Curating Our Digital Future

Looking ahead, Marlies says she and the MAK are excited about the advancements in immersive reality simulations. Their department is actively exploring ways to incorporate more virtual and augmented reality components. She sees promise for the technology to bring the museum to distant patrons, and offer the opportunity to interact with digital replicas of artifacts too fragile to display in reality. The virtual realm has its limits, though, as nothing compares to being inside the Viennese institution itself.

In the bigger picture, she’s interested to see how our new technology will turn around to change us. Like the way the iPhone turned everyone into photographers and digital socialites with the onset of social media, she’s looking out for the ways that LLMs and our ventures with emerging digital technologies will shape us individually and collectively.

Marlies encourages listeners to see /imagine: A Journey into The New Virtual, an online collection of digital realms exploring the social, ecological, political, and infrastructural considerations of virtual space. In Vienna, the MAK is hosting “edging,” a solo exhibition from Hong Kong-based animator, Wong Ping, whose colorful animations humorously reflect on the complexities of 21st century society.

Links Mentioned in this Podcast

- MAK – Museum of Applied Arts

- Hello, Robot. Design between Human and Machine

- ARTIFICIAL TEARS. Singularity & Humanness—A Speculation at MAK

- The Singularity Is Near

- LaTurbo Avedon

- La Turbo Avedon Pardon Our Dust MAK

- AImoji: AI-generated Emoji

- Uncanny Values

- edging

Continue the Conversation

Thank you, Marlies, for being our guest on Creativity Squared.

This show is produced and made possible by the team at PLAY Audio Agency: https://playaudioagency.com.

Creativity Squared is brought to you by Sociality Squared, a social media agency who understands the magic of bringing people together around what they value and love: https://socialitysquared.com.

Because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists.

Join Creativity Squared’s free weekly newsletter and become a premium supporter here.

TRANSCRIPT

Marlies: [00:00:00] Most of literature and films that describe a utopian scenario are kind of creepy. So if you really look closely, this utopian world is not good. It’s also a dystopia and that’s sometimes overlooked and that has been widely discussed, but utopia can very quickly turn.

Helen: Discover thought provoking exhibits that interrogate technology through art with Marlies Wirth, the curator for digital culture and head of the design collection at the MAC.

Helen: The Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, Austria. As a curator and art historian, Marlies explores the cultural, social, ecological, and political impacts of the digital age and the role of art and design in re-imagining our relationship with the planet. Exhibits Marlies has curated and that we discuss in today’s episode include “Artificial Tears,” “Hello Robot,” design between human and machine, “Uncanny Values,” artificial intelligence, and “You, Pardon Our Dust,” “Imagine a Journey Into the New Virtual” and “Edging.” Each explores technology’s impact on society and culture beyond their surface design, which is a lifelong passion and pursuit of Marlies’, who also regularly takes part in international lectures, talks, and juries on art, design, and digitalization.

Helen: Alongside her institutional work, she also develops independent exhibition projects with international artists and writes essays and texts fro publications. I’m a proud member of the Austrian Chamber of Commerce Bold Community, which brings people together across disciplines who are shaping the future and was connected to Marlies through another Bold member, Latte Kristoferitsk.

Helen: In today’s conversation, Marlies discusses the relationship between humans and machines and what makes us uniquely human, like our tears, which can’t be automated. We also explore singularity, identity play in immersive environments and the need to address corrupt human data, which can lead to issues like racial bias and crime prediction.

Helen: Join the conversation as Marlies reflects on the profound impact of digital technologies on culture, such as how the iPhone and social media have fundamentally changed how we interact with the physical world. Enjoy.

Helen: Welcome to Creativity Squared. Discover how creatives are collaborating with artificial intelligence in your inbox, on YouTube, and on your preferred podcast platform. Hi, I’m Helen Todd, your host, and I’m so excited to have you join the weekly conversations I’m having with amazing pioneers in this space.

Helen: The intention of these conversations is to ignite our collective imagination at the intersection of AI and creativity. To envision a world where artists thrive.

Helen: Marlies, it is so good to have you on Creativity Squared. Welcome!

Marlies: Thank you so much Helen, for having me.

Helen: Yeah. It’s so great to have you on the show. Marlies and I got connected through the Austrian Chamber of Commerce; Latte – who was at the Bold Unconference – and soon as she heard about the podcast she was like, “Oh my gosh, you have to meet Marlies.”

Helen: She’s the curator of digital culture. And the head of the MAK design collection at MAK Vienna, which is the museum of applied arts in Vienna. And we’re in for a treat today ‘cause Marlies has done so many amazing curations and exhibitions. But for those who are meeting you for the first time, can you kind of share a little bit more about who you are, what you do, and your origin story?

Marlies: So, as you said, my name is Marlies. I was born and raised in Austria, in Lower Austria. Went to Vienna to study art history which has ever since fascinated me, but I soon learned that I want to work with contemporary art and contemporary design like with the living and the contemporary culture, also of digitalization and of, yeah, the problems we are facing today.

Marlies: So I’m more than happy to work at the MAK, the Museum of Applied Arts, that holds a vast, majority of historic collections, but also [for] contemporary ones, contemporary art and the collection that I’m heading, design and digital culture.

Helen: It’s so good to have you on the show. And for those who aren’t familiar with the MAK museum, can you tell us a little bit more about MAK and the philosophy of the museum as well?

Marlies: Yeah. So the museum of applied arts was founded in the 19th century. It has a historic building on Stubenring in the center, in the heart of Vienna, and its collections are divided by materials, which is very special based on a system defined by Gottfried Semper the architect and theoretician of the 19th century.

Marlies: And so, to ensure that the materials are stored and conserved and researched properly, it was divided into like glass, porcelain, textiles, wood, metal, and others. And then later on, we started adding to these collections, materials that might not have been common in the past, but are now. such as digital productions or installations or even, yeah, plastic and its synthetic materials that have not been in existence in the past.

Marlies: And what we do apart from showcasing our collection is focusing very much on societal topics, like, topics that engage with what is a grappling theme of our common society right now in our global world. And these are topics such as digitalization, the use of technology, the way that our use of the internet or technology is changing culture as well, and the way we perceive originals or even exhibitions and artworks and I am, [specifically] in the Department of Design and Digital Culture, I’m looking at creatives all over the world; artists designers and architects who are always the avant garde when it comes to using technology and digital tools and I’m looking [at] what they’re doing with these and how they are being critical about digitalization.

Helen: Yeah, I love that. And I know you’re friends with Gerfried Stocker at Ars Electronica. And one thing that he said in our interview is [that] art is such a great tool to interrogate some of these things. And I feel like your exhibitions have really interrogated a lot of societal themes. And I know, like, even though AI has really – with Chat GPT and generative AI – has really captured mainstream attention this year, you all have been playing in the space for a while.

Helen: And one of the first exhibitions I’d love to hear you talk about is the Artificial Tears, Singularity and Humanness Speculation. And that was back in 2017. So can you kind of tell us what the inspiration was for this and a little bit of the, yeah, set the scene for us about this exhibition.

Marlies: That’s such a wonderful project. I’m so happy that you chose to want to talk about it. It’s been a while, but it’s still a topic that’s close to my heart. So back then we were starting to work on a large-scale traveling exhibition titled Hello Robots, Design Between Human and Machine that was co curated with the Vitra Design Museum and the Design Museum Gent.

Marlies: And in the course of that the MAK and also especially my department were concerned with the research about automation and what that means for us humans, like automating our labor, automating certain processes that we used to do ourselves. What does it mean for creativity, et cetera. So, next to this Hello Robot exhibition, which was a large international corporation, I decided I have to have a look into…

Marlies: Yeah, humanness as a word or the human condition and really try and gather a bunch of artists who have been poetically observing little quirks and little things that we humans do or have, which is very special because we must not forget when we compare ourselves all the time to machines – like this trope of I’m not functioning properly today or something like that – our bodies and minds are such a great system.

Marlies: It’s even more intricate than any technology that’s been invented so I wanted to look at that somehow and also at the question: what can and cannot be automated? And there’s this funny thing. I think it’s more popular in the US actually.

Marlies: Artificial tears like the little liquids that you can use to [moisturize] your eyes if they are dry or itchy and that’s something – where I read – it’s not the same as actually having tears in your eyes, because the chemical composition of tears is different depending on the reason why you cry them.

Marlies: And I was so fascinated by that thought, and it’s really, you can look it up, it’s scientifically proven, because tears that you cry out of physical pain contain, like, little parts of opioids to calm the body and to heal you and also the act of crying; we see it much in babies and children but also as adults, it’s a physical effort.

Marlies: So you get exhausted, so you calm down and you shut down and it’s calm. It’s a natural system to calm you. So crying is an act that’s very necessary. It can’t be automated, so you can’t just put little drops in your eyes and be done with it. And yeah, that was kind of the back story of how that show came about and the works that I showed were very different in nature, but coming from, for example, film props by Dora Budor till artificial sense by John Rostead but also.

Marlies: Yeah, objects that show something that only humans can do, such as hallucinating or having a gut feeling because we must not forget not only the brain thinks and feels and works for us, also this other organ where microorganisms actually live within us, other species [00:10:21] basically, is also something that tells us about what’s right or wrong or intuition.

Marlies: So that has been an interesting thought, where you can say that not only intelligence is the defining nature of humans, although we claim to be the most intelligent species, but we have to combine it with emotion and with embodiment, which is so important because, as we know, the machine does not have other organs that also can hold memory.

Marlies: And that’s another interesting thought that I had about this. Yeah. What can be automated and whatnot is like memory. We call it the “memory drive” on machines and computers so we can save stuff that can be remembered. But we humans have a very different way of remembering things. So, we always, again, try to compare ourselves to machines.

Marlies: And so, yeah, you have your files in your brain somehow? Not true, because there’s also things you don’t actually remember. But your body knows where to turn right on the way to your, I don’t know, your mother’s house or something like that. Or you recognize a certain smell and then memories come back because the organ of smelling like olfactory sense suddenly triggers memory.

Marlies: Machines are not capable of having this multifaceted, complex, process. It’s just zeros and ones. So yeah, that was basically the underlying thought of the exhibition.

Helen: Oh, and one thing that you had said before we started recording is that in the, what is it, after the Cold War and in the sixties, we compared humans to machines and now we’re comparing machines to humans.

Helen: So I was wondering if you could kind of expand on that. Cause I thought that was like an interesting observation of our relationship with machines right now too.

Marlies: Absolutely right. It’s lovely that you brought that up. Yeah, because we thought we [could] have spare parts for humans. I mean, especially the Cold War era and this time was obsessed with new machinery.

Marlies: There was also in the film industry, a rise of films that had intricate machinery, time machines or portals or tech that could take us somewhere in like a parallel universe and things like that. So we were always obsessing over the machine, helping us expand our capabilities, which it kind of does.

Marlies: I mean, yes, but we were also comparing the bodies to machines. As I said earlier, the memory is one thing, but also body parts, like you can have prosthetics and if the hand falls off, you get a new one and it’s not that easy. I mean, we are lucky that we have this kind of medical advancements, but the holistic thought of how a body works and how humans are so interconnected through also microbes and the exchange of certain information that is beyond talking; intelligent conversation is not to be compared with machines.

Marlies: And now as you said, we are switching that off and only because there’s natural language processing, which means, okay, it has the resemblance of sentences and grammar and speech patterns that we humans do [but] it is not human. And you mentioned Chat GPT earlier.

Marlies: That’s very advanced in a way that it responds much better than maybe like 10 years ago, the early chatbots where you clearly could see and feel that was not a human. So it would not pass the Turing test, but now it’s still something that’s only learned on the basis of data, on databases, on things that exist, it can’t have an original thought because to have a thought, you would have to have the concept of the mind.

Marlies: And again, the machine doesn’t have that. It recalls memory and data from storage.

Helen: And one thing in the explanation of the show on the website is one of the elements of the exhibition is interrogating singularity, which you kind of alluded to a little bit of machines not having minds, but the futurist Ray Kurzweil is kind of predicting with singularity that we’re gonna see that in our lifetime. So I was curious how interrogating singularity came out in the exhibition as well.

Marlies: Yeah, the singularity defined by Ray Kurzweil is the concept of us and machines basically merging to be one entity, non human, more vastly powerful because combining all knowledge of humanity and machines alike.

Marlies: And it’s actually kind of like a science fiction concept. So there’s many scientists out there who are claiming that this would not actually work. And it’s a theory or like a theoretical concept, but that’s vastly different from stuff that we can pull off even with the software and hardware that’s at hand for the next 50 years to be predicted.

Marlies: I’m not an expert on tech hardware, but we saw that also in the times of Alan Turing, who was an expert on machine learning in the 1950s already, that the computing power was just not enough. He had invented a chess computer way back then, but it wouldn’t work because the power wasn’t there.

Marlies: Now with quantum computers being developed the thought is interesting, but still why would that happen. So, yeah, many scientists find the singularity highly unlikely, but if we would take it in for a moment as a basis for this exhibition, that would mean yeah, the minds of humans, machines merging, and it’s being like a God-like kind of holistic being that knows everything and has access to every feeling and information in the world.

Marlies: And that has been compared to drugs, actually. And one specific one is called DMT. And it’s a substance that occurs in nature. And I have been told, didn’t try it myself, that it creates some kind of the best and most connected feeling with the universe and all beings that you will ever know. Lasts only very shortly.

Marlies: And the artist Jeremy Shaw did work on that. It’s called DMT. It’s from 2004. He did that as an experiment with some fellow artists and friends. And what we showed in the exhibition was this piece. It’s the faces of the people on little screens. So, it’s the human likeness, but represented by a machine body as they try to describe what they see and feel while having this experience.

Marlies: And that seems to describe a little bit what Ray Kurzweil is thinking, like this massive feeling of being one singular organism and train of thought with all the machines in the singularity.

Helen: That’s so fascinating. So, if I understand what you said correctly, the altered state as related to our consciousness being connected to oneness is like what Kurzweil is saying is singularity with the help of machines that will be able to achieve that with, without psychedelics.

Helen: Is that correct?

Marlies: Exactly. Through connecting with the machines.

Helen: That’s so fascinating. Well, there was one, well, it’s actually from another exhibit that I wanted to read. So I’m skipping ahead a little bit, but we’re going to talk about an avatar a little down the line, but one of the points in the exhibit, and this is an excerpt, kind of talks about eternity and whatnot, which we’ll get to, the little excerpt from the point is: “is this right now, is this yesterday, today, tomorrow, forever, never had I been, I had always been, I will always be, I can see this room, every room at once, recollected.” And I feel like that kind of captures that of everything all at once, or what is the name of the movie, “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once,” or something, kind of capturing that sentiment.

Marlies: Yeah, that’s a great take that you have there to combine that because LaTurbo Avedon is a very interesting character. They are a digital avatar and artist and curator, and I’ve invited them to have the solo show Pardon Our Dust at MAC in 2022. And as a digital being, not being embodied in a physical world LaTurbo Avedon has access to this kind of different way of thinking about the singularity and the ways that you can be in the past, in the present, the future, and everywhere at once as an avatar online.

Marlies: We can do that too. So our likenesses of our Instagram accounts or TikTok or Facebook accounts are out there as we are here, at the same time in this software. So, as a digital presence or digital image, as we know, we can be anywhere. And that’s kept us that sentiment very much. And the avatars, basically a representation of us online as a digital creature. It comes actually from Sanskrit being like [the] gods coming down to Earth and representing in, in a human shape. And we use that word to be represented in a digital code on the internet.

Helen: I find that so fascinating, especially since, well one, I think I told you I’ve digitally cloned myself with a hyper realistic avatar and I think we’re just going to see more and more of these but beyond even the type of clone that I have there’s already the tech out there to have more interactive clones where you can feed your own data to it.

Helen: And so, not only is it a digital likeness that looks like you, but it can respond in your voice based on your own data and IP. So what does that mean in the relationship to this other entity that looks like me, sounds like me, and is based on my data and IP as far as our relations of representation and what not.

Helen: So I think it’s going to get super interesting really quickly on that front.

Marlies: Yeah, for sure. And I think that’s so interesting that this is starting right now because humanity has dreamed of that. I’m always jokingly saying where’s my clone at, when we have stressful exhibition installation periods where we would need some more of me.

Marlies: But now it’s being real, at least online, and we can send our digital representation, for example, to a talk or giving a lecture. If we feed the data in correctly, that digital avatar could actually give a lecture somewhere while I’m doing the podcast with you. So that is the next step of automation.

Marlies: That’s going to be very interesting. And what I also think is it might help humans to rethink a sense of self. We are all kind of sometimes struggling with that. And especially people who are not happy with their like embodied presence or have different gender fluidity and things like that.

Marlies: I think it’s really helpful and interesting to use this avatar to try to find one’s personality and then maybe some people change in real life too, to resemble more [of] the likeness of the avatar that they’ve created and designed for themselves. So I think that’s a very interesting topic.

Helen: Well, even if you take just Instagram, how people have more of their ideal lives, like, are you taking this photo because it’s actually a scene that’s authentic to your life or an idealized scene that you want to capture and show on Instagram, of like this more idealized life that you’re striving for? But one thing I was thinking the other day [is] that I think one of the futures of play might be identity play. So you have your avatar and you can play with it.

Helen: Maybe a different genders, different scenarios. And it looks like you, sounds like you, but without the constraints of time and space in our physical worlds, [you] get to explore some of that identity more, which I think is a kind of interesting with the metaverse; all these immersive experiences with avatars and whatnot.

Marlies: Definitely. And you’re also saying like identity plays kind of already going on a lot in virtual computer games, right? So you have world building, you have whole different dynasties and worlds and scenarios that are far from real in these fantasy kind of games.

Marlies: And you can insert yourself there with your avatar and be these characters and play out these different lives in different eras and periods or regions of the world. So that’s already in full bloom. And the gaming industry is also really touching on culture and coming closer a lot because it’s becoming more interesting also to artists and designers to design these worlds and to engage with these topics and use game engines, which are super high tech; feed software to create these worlds that are large and have to change and be online for multiplayers, so that’s sparking a new interest of the art team as well.

Helen: That’s amazing. And I heard some stat the other day that the actual gaming industry makes so much more money than TV and film.

Helen: So I don’t have that stat, but it wasn’t surprising to me just because of the immersive way that you interact with games. Well, you kind of introduced the avatar, but why don’t we skip ahead to LaTurbo Avedon and kind of tell us a little bit more about this because you mentioned it’s a an avatar but tell us about the inspiration for this exhibit, who this avatar is and what you were interrogating with LaTurbo Avedon.

Marlies: So yeah I encountered the work of LaTurbo Avedon online as is suitable for a digital presence and I found it really interesting that The character or the artist never shows themselves physically anywhere. So it’s really only the avatar who interacts and the avatar also always changes. So the turbo agent was basically born in 2008 online in the computer game Second Life.

Marlies: Some of our listeners might remember that it turned into a capitalist trap soonish, but in the very beginning, it was really interesting. And exactly this kind of open world where everyone could look like a very crazy avatar or like an animal or you could take any identity and just gather there and interactions with real people all over the world represented by their avatars.

Marlies: It was – for the time being – it was very progressive. And LaTurbo Avedon soon noticed that creating a digital identity in different computer games or different online spaces really helped to find their identity and idea of what their art should be about. And the show was titled Pardon Our Dust.

Marlies: And that’s if some of you remember, also this kind of signage we had in the old internet where websites were under construction and you would use like the same language you did on construction sites in the actual physical world. And now we are building the new immersive web three, the internet that’s also coined “the metaverse,” which will be much more spatial and which will be less like flat with browsers and clicking yes and no fields and things like that, but rather walking into space maybe with your own avatar maybe with your VR glasses on

Marlies: So it will be a different experience of how information is being accessed. And the problem with building new things online [is that] it’s always large private global corporations who will then try and use this for their own progress and profit and create kind of walled in gardens that are not open, that are not accessible or inclusive to many people because they are for profit spaces that will use data and ads and you name it, to make a profitable income and LaTurbo is really interested in having that discussion around: why is there not a free, openly accessible internet space anymore, kind of?

Marlies: Everything’s kind of privatized. It’s like properties around lakes or on the seaside. There’s hardly any space left where you can just go and enjoy what is actually a common good, a lake or the ocean. And the same is for the digital world.

Marlies: So, if you privatize every website, every space there is, how can creatives thrive? How can non corporative entities thrive and access information? How can there be critical interaction if everything is owned by private corporations? So this was the underlying kind of theme of the show. But it was very beautifully and poetically woven into a six channel installation in the MAK gallery, like a kind of immersive experience [where] we could sit down and really see the narrative unfold, the images unfold on these six screens with the avatars being present on smaller screens narrating the story and yeah. It was an endless loop that was ever changing, so slightly showing a world that is permanently under construction like construction inside forests, flooded suburban cities hints towards the crypto bubble that had just recently bursted.

Marlies: Yeah, some photos are visible online.

Helen: I’m so sad I missed all these exhibits, but it’s so great to hear about them. And it’s really interesting what you’re saying about the walled gardens of the internet, because, you know, it seems like when the internet first came about, the promise of it was this more utopian access to information and connectivity of human knowledge and humans to humans and the web 2.0 versions of the internet.

Helen: But it seems like with the different types of metaverses, or whatever people want to call it now, that they’re even more specific to the creators, creating them and not interoperable. So it seems like it’s even more fractured versus interoperable, but with some of the blockchain technology, it seems like we might have the wallets where our identities will carry along with us, but as you were saying, [that] goes definitely against the corporation aspect of it that wants to keep everyone on their platform or in their worlds all at the same time. So it’ll be interesting to see how that plays out.

Marlies: Definitely. And yeah, the blockchain technology is something to watch for sure. Also the concept of the DAO, the decentralized autonomous organization. We at the MAK were just in the progress of founding one and currently in the conceptual phase, looking to see how we can use this kind of bottom up decentralized community building as a cultural institution.

Helen: Well, there was one thing in one of the interviews in an article I read ahead of this interview that I thought was really interesting that you had said about the difference of looking towards utopian and dystopian futures because often on the show what’s come up in conversation is like, we have so many dystopian stories out there that if that’s all we hear, that’s what we’re going to manifest versus there’s not very many utopian stories with AI for us to like, look forward to, but you actually kind of like the dystopian.

Helen: So I was wondering if you could share why in your reasoning behind that? Cause I thought that was really interesting.

Marlies: So yes, I do like the dystopia as a concept, I don’t want it to happen to us, but I always say that because I think utopia per se is dystopia. May not sound reasonable to you yet, but let me explain.

Marlies: Most of literature and films that describe a utopian scenario are kind of creepy. So if you really look closely, this utopian world is not good. It’s also a dystopia and that’s sometimes overlooked and that has been widely discussed, but utopia can very quickly turn. And if you take, for example, the Godard film, Alpha Will, where there’s a perfectly fine utopia, but for example, crying, poetry and a third thing are forbidden by law.

Marlies: And then you see how this kind of changes society. So if you can’t write a poem or cry, it’s a dystopia already, right? Even though these instruments were brought upon this state, this fictional state to help people not be sad and be, you know, not fight over things. But it doesn’t work. So that’s why I thought any utopia will turn into a dystopia at some point.

Marlies: And especially if you look at the AI discussion that you had brought up. I don’t believe that AI suddenly will in the next few weeks take over the world and produce paperclips and kill us all, but the scenario behind these very drastic ideas or concepts that have been put out there by scientists is obviously how machine learning works.

Marlies: So it’s not impossible that a machine will overtake something, override something, because it uses self learning based on data, but that’s why it’s so important to have this discussion, especially with artists, within the avant garde of these people who look critically at what AI does. There are many great people out there in the art industry that are critical towards these technologies and show through their art pieces and installations, which helps us to have a more graspable approach to these technologies to understand the dangers ahead. And to also understand that it’s us humans who need to do something about our kind of way that we interact with data and what we’re feeding to AI.

Helen: I think that’s so interesting. So the utopian is still dystopian. And if I understood what you said correctly, we still need to use that as kind of a signal of how to navigate the future as kind of like just a tool to interrogate things now which I find so fascinating. Well, you mentioned the artificial tears again, and I did hear, and I don’t know if it was you who said it to me or someone else recently, that every tear is actually almost like a snowflake composed completely different.

Helen: So they’re all completely unique. So I thought that was super fascinating too. But following that exhibit, the next one that you did that explored AI and technology was Uncanny Values, which I find is an interesting thread of going to “what is human?” to kind of, the symbolism and representation of human emotions through emojis.

Helen: So I don’t want to steal your thunder, but tell us about Uncanny Values, Artificial Intelligence In You and more about this exhibit.

Marlies: Yeah, that was a really great research. I did that show together with a media theorist [name] and we worked also with Process Studio, a graphic and interaction design studio who we had briefed to develop one little thing that will be the main feature of the exhibition promotion and that was AI generated emojis, short AI emojis or AImojis. And we thought it’s so interesting that we try to convey in our digital world, our emotions, since we don’t always FaceTime each other.

Marlies: So we text and then emojis were created to represent a smirk or like a wink or a smiley face or a sad face. And they’ve become [ever] more intricate and there’s more representations of things available now. And we thought that’s such an interesting concept of how humans try to make an abstract little icon of their likeness, trying to convey a very complex thing, that is, body language and emotional display during conversation, and sometimes more successfully than other times in this emoji.

Marlies: And we thought it would be so interesting to see how early, it was in 2019, that exhibition, how early DAO networks, machine learning concepts would come up [and] what they would come up with. And yeah, the results were rather disturbing, but we still use them for our poster campaign. And especially so because the title Uncanny Values also refers to a term by Masahiro Mori, a Japanese computer scientist who coined the term “uncanny valley” as this little dent in our trust towards human looking but not human creatures.

Marlies: Such as puppets, masks, clowns, zombies, dead people, body parts, prosthetics, they all fall into that kind of, which gives us a little shiver because it seems like it’s us, but it’s not. And that also applies to humanoid robots, androids represented in films, where you just see there’s a little bit off.

Marlies: It’s not actually human. So this kind of uncanniness and the uncanny I have to insert here is a term also coined by Sigmund Freud, the Viennese psychoanalyst. And it means creepy, eerie. And in the field of ethics around AI, we chose to have this title mashed up, uncanny values, because also our human understanding of morals, rules, and ethics is kind of uncanny at times, because it doesn’t always do humanity justice, one might say.

Marlies: So we thought that would be an appropriate time to look into artworks and pieces that are critical towards the bias that is also coming with any data put into machine learning, right? Because we are just humans and we do make mistakes and wrong decisions. We have different sorts of political directions and governments.

Marlies: And then throughout history, there’s a lot of data accumulated that later on proves to have been wrong, but it’s still there. We did not erase it or delete it from the global storage. So it’s still out there and machine learning algori

thms still use it. And yeah, that can lead to terrible outcomes. And yeah, that was a part of the topic of the exhibition.

Helen: Well, for all of our viewers and listeners we’ll be sure to put the images on the dedicated blog posts. Cause I know it’s hard to not see them and just hear about them, but they kind of look like, almost like grunge and smudged emojis with like different looks to them. But what was the reaction to these emojis in the exhibit?

Marlies: Yeah, mixed, I would say. There were many fans. We also had stickers and buttons. They’re all gone. So, the fan community out there had their fun, but there were also people like, “what is that?” Like being horrified, because as you said, they looked a little bit like emojis being shot in the head and kind of left there, but others, I mean, they’re different ones.

Marlies: Others were really cute. Yeah. Interesting how that turned out because the concept of a little abstract icon is very hard to learn actually by machine.

Helen: Well, one thing that I find fascinating about emojis is how much thought goes into selecting them sometimes in our forms of communication and like how we want to convey a certain feeling or sentiment. For one, networking icebreaker.

Helen: Sometimes I’ll ask people to share like, what’s your name, where you’re from, what’s your favorite emoji. And sometimes I get these reactions that’s like so personal that people don’t want to share what their favorite emoji is. But it’s fascinating to go from I guess the different types of communication and conveying what we’re trying to feel from emoji or like text emojis, GIFs, and now we’re going to have avatars in film.

Helen: It’s just kind of like, what medium best represents what I’m trying to feel and to share that out. So I think it’s a really interesting exhibit from that. But one of the things, part of this exhibit too, you mentioned the bias and how there’s like corrupt human data. So can you expand on that a little bit more for us?

Helen: Like kind of what came up in your research or the exhibition related to bias and data?

Marlies: Yeah, there were especially two, actually three works that dealt with that topic in very different ways. And one, which was our entry piece, which was very much conveying the Uncanny Valley effect, was [a work] by Heather Dewey-Hagborg that was trying to use machine learning to reconstruct how the whistleblower Chelsea E. Manning might look like, based on only samples of their DNA.

Marlies: And this sounds very complicated, but actually [there] was research done that if you put DNA samples in machines, machine learning algorithms can, based on data of other humans and their DNA, design basically a face of that’s what this person with this DNA might look like to identify them, maybe crime suspects, et cetera.

Marlies: But the thing is the installation was comprised of all the little hanging faces of so different kind of body height, skin color, skin texture, hair, male, female. So it was like, okay, one DNA sample from the same person, Chelsea E. Manning, came out as all these figures. So it doesn’t work obviously, the technology failed, but still, it shows that the idea exists that we can use machine learning to identify suspects, for example.

Marlies: And there was this huge scandal actually around machine learning about crime prediction, because based on data from US states with a high prison density and population there were lots of people of color incarcerated for many reasons. Also, again, mistakes from the past to be mentioning the war on drugs and things like that.

Marlies: So there’s this, all this data of past criminals and prisoners that are of black skin color. So the machine learning algorithm inevitably will learn from this past data and predict that crimes will be done by black people. So obviously wrong. It was a huge scandal and that this was even considered and that’s what I mean when I always say “corrupt human data,” because this data is not high quality.

Marlies: It does not enable a machine to properly predict who’s going to commit crime and who won’t because the whole system is kind of crazy. So, this was information that Dewey-Hagborg also considered when doing that work and especially choosing Chelsea E. Manning as a central figure also to technology to government and political related topics and also a person who is gender fluid and then changed, like, their pronouns and their identity.

Marlies: So even more complex in looking at what the DNA comes up with. And as an installation, you will have pictures. It’s also made for an uncanny entrance to the topic. And another work or artist who is always concerned with this kind of bias and information is Trevor Paglen. American artist who has become known with his very radical and critical work also investigating surveillance technology, how our data is being used and also together with Cape Crawford Has done extensive projects on AI and machine learning and how our data is being used and misused in this regard.

Marlies: And we showed a piece by him where he showed the background actually of machine learning, the huge image databases that are out there and are used for machine learning, one of them is called ImageNet and it has photos where it’s also always in discussion if it was ever cleared if people gave the permission to have these photos used.

Marlies: I don’t think so. There’s also a project by the way, where like you can request your face [be] removed from any machine learning database by Holly Herndon. But this showed a video with very fast changing images from ImageNet and a very great soundtrack by aforementioned Holly Herndon, also AI created, and it was so mesmerizing for our viewers and for us curators when we first encountered it, to see this vast amount of image information that is shown in there and that machine algorithms can identify in a number of seconds.

Marlies: They can see what it is. We humans only have a blur. So that makes this kind of frightening thought of machines maybe really [will] overtake us. But then again, we all know the wonderful invention of ReCaptcha, the thing where you have to prove to be human by identifying traffic lights.

Marlies: And this again proves that machine is not so smart because they can hardly do it.

Helen: Yeah. Thank you for expanding on that. I feel like we’re just scratching the surface and can go on and on. But I know we’re coming close to time on the interview; as someone who has thought deeply about all these subjects and done a lot of research on exhibitions, interrogating different subjects.

Helen: What are you currently thinking about? Like, what are you mentioned DAOs but related to like AI and humanity and culture, what are some of like the current questions that you’re kind of marinating on related to this space.

Marlies: Yeah. So, actually the term “digital culture” that has been woven into my job title is something that I’m currently and always expanding to think about and talk about with other people and creatives, because I think it’s so interesting how culture changes through technology.

Marlies: And if we use the word technology, not only for digital technology here, but we have to look at technology as also electricity or agriculture. All these are technologies. And then we have now very advanced digital technologies and how this has impacted the way that the world has developed or the cultural aspects have developed.

Marlies: That’s something that interests me always. So, also especially to see through the eyes of artists, designers, and architects who have been deeply concerned with these topics, because that’s a main thing that I love to do when we do these kinds of exhibitions and research to invite artists and creatives to show us the world through their eyes, through their work, because it’s so much different than reading an article on AI, which I always do, obviously, but seeing an installation that has, that is conveying some of these topics and research, but through, you know, an artistic kind of sense or a very interesting kind of spatial setting.

Marlies: So yeah, that’s one thing. And also the notion of augmented reality is currently interesting to us because you can do so many things being in the contemporary context, but also, concerning historical artifacts that may be too fragile to be opened or touched. You can do interesting things with augmented reality there and like extended reality.

Marlies: I think that’s a great concept. And ever since it has been used in films like the Minority Report back in the day, now we actually live in a world where this is no longer sci-fi. We can actually use that. And the question will be, how will we use that? And in the machine context, I think AR is an interesting topic that we are currently looking into more.

Helen: I know one of the cool things about VR and AR and MX, mixed reality, extended reality, there’s so many different names, immersive experiences, is the application of where you could go to any museum or place in the world and experience it without having to physically be there. So is that something that you all are doing or have explored at the MAK as well?

Marlies: Not so much, actually. I mean, I think it’s [an] interesting and very inclusive way to, to include more people, the world who might not be able to travel for several reasons. And I think it’s a beautiful idea to make that happen. We haven’t done it yet. But also I have to stress that the physical museum visit is also irreplaceable because not only is there textures, smells, we had that early in the conversation when we started with artificial tears, we have this like, yeah, is it warm or cooler in the exhibition space?

Marlies: How does the floor feel like that I walk on? And also, especially the social aspect, the presence of other people you might or might not have come with to the museum, maybe strangers, maybe your friends and family, that you encounter there and together you look at something and you’re both interested in that thing at the same moment, and that can lead to very interesting emotions or conversations.

Marlies: And I think we would lose that if we only do it in VR, but also recently on a panel [of VR artists said] that, you can also have social experiences in VR. And that is also true. So I’m very excited to see what the future will bring in that regard.

Helen: I am too. I’m a big believer, for as much as I live digitally, my life is online, that you can’t replace in person presence.

Helen: But I also know some technologists are trying to recreate presence digitally, which I personally don’t think that we can replicate that, but I know some people are working on that, which I find really interesting. To your point on the digital cultures, I loved how you explained that.

Helen: Could you give some examples? And actually one interview, I discovered Solar Punk as, like, an interesting cultural movement to kind of counter Cyberpunk that’s more utopian. But what are some of the digital cultural trends that you’re seeing in your conversations with the artists and stuff?

Helen: Yeah. I’d love to hear more about that.

Marlies: Yeah, well, as you’re mentioning Solar Punk, there’s also one very important movement that’s Afrofuturism and that also reimagines basically the future of the African continent that is famously being mined for all the rare minerals that we use to put in our deck.

Marlies: And the country or the continent itself, many countries on the continent are not benefiting as much from that fact actually. So I think that’s an interesting turn that has come out of that. And I think maybe the most dominant one that we still experience now has been the advent of the first iPhone in 2007, because what at first was kind of, yeah, okay.

Marlies: It’s a smartphone. You can, it’s a flat screen. It’s like a little black box. But it’s not about this surface design, which is also slick and nice. But it’s about the interface design. And I think the term “interface” has been very poignant for digital culture of our time, because the interface suddenly enables you through a device that has formerly had limited functions such as calling someone or texting or making a photo, now is connected to the Internet and [has] enabled other platforms and applications to even come into existence.

Marlies: We didn’t have that before. So then [social media was] born. Now social media is slowly turning into social technology, which might be an interesting time to live in. And I think this kind of way through smartphone usage, widely spreaded, we changed our cultures because it’s now normal that you take photos of nearly everything you see.

Marlies: I mean, not everyone’s like that. I’m like that. But you can [then] share that immediately online, or you can live stream from anywhere you are in the world. You can have your precise location. So it really changed the way we also interact with the physical world. And that’s what I find so interesting, how it always trickles back.

Marlies: So digital advancements don’t stay in the digital realm. They trickle back into our physical reality and change the way we go about that. So, yeah, that’s one interesting train of events where I think how will that change now that we have more natural language processing, for example? And will we use our voice more to interact with our devices?

Marlies: Does everyone really like it? I don’t as much, especially in public space. Like I would imagine it to be really weird to be speaking out loud to my devices all the time. But yeah, that’s one thing that’s trending and I find it interesting and it would be great to see how our culture will change if we start, you know, talking out loud to our tech all the time and obviously these kind of yeah, Chat GPT that was mentioned earlier, these kind of technologies that would pass the so called Turing test, and it’s hard to to see if it’s human or non human, how that will change, for example, literature.

Marlies: Text production can be an interesting cultural shift.

Helen: And I think another interesting thing on that front is not only are we talking to devices more, but with Neuralink and the brain computer interface, I mean, the tech already exists where you can think. And then the machines will take your thoughts and turn them into images or video.

Helen: So it’s like, talk about manifesting from thought to reality in a digital sense, like that tech exists and like, what’s that going to mean for society and culture too.

Marlies: That is so fascinating, Helen, because that’s again, a dystopian sci fi narrative right there. It may help some people and it’s being used right now in medicine.

Marlies: But just think what you can do with that can go wrong. So it’s going to be an interesting time to experience that.

Helen: Oh, we’re not short of interesting times at all.

Marlies: No.

Helen: At all. Well, for our listeners and viewers, is there anything specific at the MAK that you want to promote or plug? Current exhibitions that you want to share with the Creativity Squared community?

Marlies: Definitely, one that is no longer on view, but the website is still out there is TheNewVirtual.org. It’s a show that was concerned with, yeah, the virtual space and how the new world building narratives can be used to create also tropes around ecological concerns in conjunction with technology, which is also really important to think about.

Marlies: And the current show that’s just on view is the solo show of Wong Ping, a Hong Kong based animation artist show is titled Edging, and it shows four short animation films that deal with many of our emotions and problems and tensions that we have in our globalized digital cultural society at the moment.

Marlies: And it’s really fun and interesting to see those.

Helen: Awesome. Well, I hope I can get back to Vienna soon to see all the exhibits because I was there, I think before the space one ended. I’m so bummed that I missed it, but definitely anyone who’s got Vienna on their travel list, add MAK as a stop on that.

Helen: So one question that I always like to ask our guests is if you want our listeners and viewers to remember one thing or walk away from our conversation with one thing, what is that you want them to remember?

Marlies: That design and digital culture or digital tools are always more than their surface or them being an object.

Marlies: They always have some kind of impact on the way that society changes, maybe even political changes. So, be mindful of that and embrace it.

Helen: I love that. Well, Marlies, it has been so wonderful having you on the show. Thank you for your time and sharing all the amazing projects and your thoughts and inspiration and the artists who brought them to life in your exhibitions.

Marlies: Thank you so much for having me on Creativity Squared, Helen. It was such an interesting conversation and I think, I have a feeling we could talk more for hours, but we will leave it at that.

Helen: Thank you. Well, we’ll definitely have to bring you back on the show because I know there’s definitely a lot more to talk about.

Marlies: Would love that. Thank you.

Helen: Thank you for spending some time with us today. We’re just getting started and would love your support. Subscribe to Creativity Squared on your preferred podcast platform and leave a review. It really helps. And I’d love to hear your feedback. What topics are you thinking about and want to dive into more?

Helen: I invite you to visit CreativitySquared. com to let me know. And while you’re there, be sure to sign up for our free weekly newsletter so you can easily stay on top of all the latest news at the intersection of AI and creativity. Because it’s so important to support artists, 10 percent of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized nonprofit that supports over 100 arts organizations.

Helen: Become a premium newsletter subscriber or leave a tip on the website to support this project and ArtsWave. And premium newsletter subscribers will receive NFTs of episode cover art and more extras to say thank you for helping bring my dream to life. And a big, big thank you to everyone who’s offered their time, energy, and encouragement and support so far.

Helen: I really appreciate it from the bottom of my heart. This show is produced and made possible by the team at Play Audio Agency. Until next week, keep creating.