Ep23. Art, A.I. & Immortality: Explore the Human Urge to Create, Transcend Reality, and Express Consciousness with Creativity Squared Writer Jason Schneider

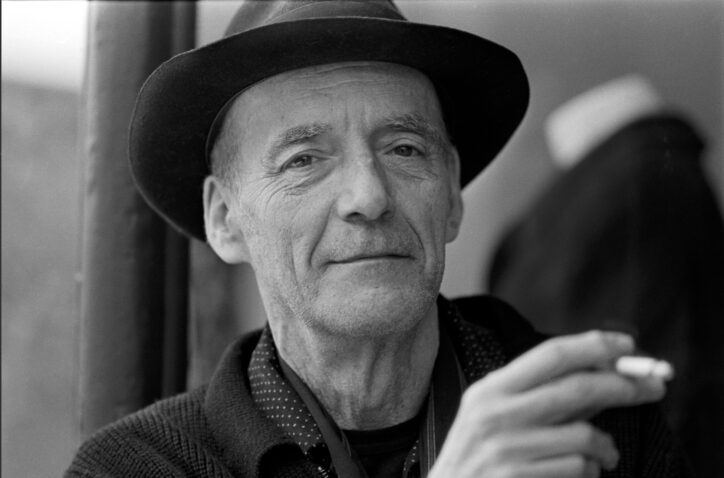

Jason Schneider is a modern day Renaissance man: photographer, writer, philosopher, collector, and poet, to name a few of his passions. He developed a youthful love of photography into a fruitful career in media over 18 years as monthly columnist and Editorial Director of Modern Photography, followed by 16 years as Editor-in-Chief of Popular Photography. He’s seen every inch of the photography business, through roles as a photojournalist, commercial photographer, and camera test manager. He carries a profound knowledge of cameras and their functionalities, in fact his writings over the years are compiled and published in a 3-volume series on camera collecting.

Jason was also an integral contributor to the Leica Camera Blog. And yes, if you’ve been following the Creativity Squared blog, you will recognize Jason as the author of previous posts exploring the meaning of art, the existential implications of A.I. on photography, and consciousness and art.

Despite the labor and love that Jason’s poured into photography, he isn’t hostile toward A.I. image generators like Midjourney and DALL-E 3. He’s doubtful that A.I. will make the photographer obsolete, and he’s confident that no matter how advanced technology becomes, art will always require a human touch.

What is Art?

Jason says that art is humanity’s “defining passion.” It’s something that humans, and only humans, have engaged in since the Stone Age. Now that artificial intelligence is eroding humans’ monopoly on intelligence, it’s worth examining the fundamental dynamics of our relationship with art.

Jason believes that our human drive to create art comes from our awareness of our mortality and our desire to leave something of ourselves behind, in un essai d’immortalité, an attempt at immortality.

This innate desire is enabled by humans’ unique ability to represent their world through symbolism.

“One of the signal and identifying features of human consciousness is the ability to abstract – to take significant details and present them in a symbolic form.”

Jason Schneider

So art is uniquely human, and the creation of art is reliant on humans’ ability to process their surroundings and distill it into an image or a word or mathematical symbol. But what distinguishes art from the other modes of symbolic representation like math and language?

Jason points to specificity and selectivity. Art is representation, and a representation is inherently less than the thing being represented, so the art of representation comes down to deciding which elements to depict and, just as importantly, which elements not to depict.

Jason invokes the ever-concise Emily Dickinson to illustrate his point about art being a process of selective representation. In one of her short poems, Dickinson articulates the idea that even our best attempts at representation often fail to convey the entirety of meaning:

Could mortal lip divine

The undeveloped Freight

Of a delivered syllable

‘Twould crumble with the weight

Emily Dickinson

Ironically, this understanding of art resembles the way that A.I. diffusion models generate an image from a prompt – starting from a canvas of pure digital noise, like the world around us, and systematically reducing that noise until the artist’s vision emerges.

“You’re taking a specific thing out of the great tumbling reality around you and requesting that the viewer pay attention to this particular thing. And it’s a representation of the larger sense of how you view the world or specific aspects of your experience.”

Jason Schneider

Much of the discussion around A.I. art right now focuses on where the threshold should be for attributing creative ownership. How much credit should Midjourney get for creating an image based on a prompt, which is a user’s description of an image in their mind?

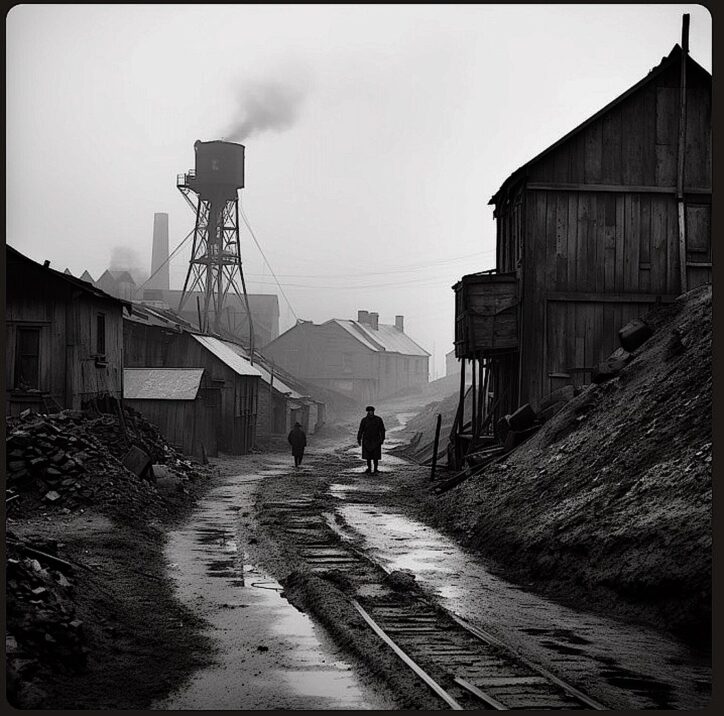

Jason says he’s created art with Midjourney that he would happily enlarge and hang in his home. He’s prompted Midjourney to create images that look like they’re straight out of a museum, depicting a gritty, gloomy coal town and an old-fashioned headshot of a “woman” resembling an early 20th-century actress or model.

The texture – the way that they appear to be a photograph developed from a film negative, the lighting, the overall sense that you are looking at a genuine photograph – is the most impressive aspect of those images. While the A.I. model already possesses all of the knowledge to create such an image, Jason’s role cannot be overlooked. If not for his intimate knowledge of various camera technologies, photo compositions, and technical camera skills, would the A.I. be able to create such a compelling image?

Jason says that as long as there is some level of human element involved, something created by A.I. can indeed be a work of art attributable to an individual.

“Generally, one must input a set of instructions or suggestions for A.I. to do its thing, and therein lies the human element. And even though the process may entail some randomness, it is a human being that decides which images are worthy of being published or shown.”

Jason Schneider

He takes this idea to its logical extreme in a thought experiment. Imagine a surveillance camera at a bank, pointed at an ATM to automatically record images without the need for human intervention. Now imagine the ATM is robbed, so a human security guard must review hours of footage of mostly inconsequential images of people using the ATM in order to find the moment when the robbery occurred. But imagine that the security guard stumbles upon an image of a woman smashing a hundred-dollar bill into her husband’s forehead out of frustration. The human security guard did not manually record the image, and they may not have even been the one to set up the camera or point it in the direction of the ATM. But they publish the image and claim it as their own work. Jason sees no problem with labeling the image as art and attributing it to the person reviewing the camera footage. The reason being that the reviewer recognized the impact of the image out of thousands or more images that they encountered. If not for the human element – the recognition of the image as compelling – the image would likely never be seen by anyone again.

Returning to the question of A.I. art and attribution, Jason says that if he were to distribute the A.I. images he created, he would credit the image as “Jason Schneider, with Midjourney.”

Destruction or Democratization? New Technology’s Impact on the Arts, from Camera to A.I.

What will become of photography in the age of artificial intelligence? Will it become simply a medium of record, detached from the purposes of making art and relegated to serving the utilitarian need for memory preservation? Will new generations bother to learn the art of photography when A.I. image generators are easily accessible?

Jason compares our wrangling with A.I. to the early days of camera technology. At the time, some in the art community feared that cameras would destroy painting as an art form and degrade the value of art in general.

Clearly, photography did not mark the death of painting. However, Jason says that the widespread adoption of the camera created a new dynamic that changed painting into a different kind of medium.

“To a certain extent, it transformed representational painting into a much more emotional, personal, abstract kind of art. In other words, it made painting into something else, not just representation.”

Jason Schneider

So perhaps our understanding and perception of photography will change in the future. What about our understanding of what makes an artist? Jason says that the advent of the camera elicited cynicism from legacy artists, especially painters of the time, who derided the idea that “any fool” could step out with a camera and automatically achieve perfect perspective, three-dimensionality, and all the hallmarks of a great image, without needing to understand the underlying artistic concepts.

Similar criticism might be leveled against those who never created art – for lack of skill or motivation or whatever it may be – until A.I. image generators became available. Creation of compelling art no longer requires an art degree or even a passing interest in learning artistic methods.

Jason says that people naturally fear their own irrelevance when the paradigm they’re accustomed to suddenly shifts, but he believes that the labor of producing a work should not be its defining trait.

“The number of individual decision points entailed in creating a photograph, or any other work of art is irrelevant so long as the artist’s intention can be articulated and shaped in a way that expresses the artist’s consciousness.”

Jason Schneider

To Jason, A.I. is another step in the democratization of art. Just like the iPhone enabled all of us to become photographers, A.I. is enabling anyone to be a graphic designer. To update the old adage, “the best camera is the one you have with you,” the best tool to create an image is the one you can use.

Art for Art’s Sake

Jason says that it’s important to keep in mind that art, like much of humans’ pursuits, is the perpetual attempt to represent our complex world in a more digestible form.

“It’s through abstraction that we can do many great things. But it’s also very important to realize that in creating, we have selected from the complex and multifaceted reality that we experience through consciousness that all these things that we do, however great that they are, entail presenting and communicating something less than the totality.”

Jason Schneider

The medium through which we share these representations will inevitably change over time. However, no single technology can void the human instinct to create abstractions and share them with others.

Ultimately, Jason says that art and artists will continue to thrive by nurturing that instinct, much like his late daughter, Heidi, who told him once that the reason she writes poetry is that she “can’t not write poetry.” Shortly before she died, Heidi encapsulated that idea of living for the sake of living, and joy for the sake of joy, in a poem aptly titled Poem on an Envelope:

I am here but I am not

my heart tried letting go of its grievances

one by one, like letting go of balloons

flying higher until they disappear—may the space which once I occupied,

by a sweet one be filled—with the things

dearest to me—

Forsythia, gingerbread cookies,

and absolute wonder—each thing felt in my small body

-Heidi Schneider, I Am Here But I am Not

as infinite, as anything could be—

cloudless skies—dusk,

the exult smell of the forest—

lay me down to that

Links Mentioned in this Podcast

- Learn More on Jason’s Website

- Buy Jason’s Series on Camera Collecting

- The Leica Camera Blog

- Creativity Squared — What is Art Blog Post

- Creativity Squared — A.I. and the Future of Photography

- Creativity Squared — All Art is Representation, and Why It Matters: An Exploration of the Convergence of Art and Human Consciousness

- I Am Here But I am Not on Amazon

Continue the Conversation

Thank you, Jason, for being our guest on Creativity Squared.

This show is produced and made possible by the team at PLAY Audio Agency: https://playaudioagency.com.

Creativity Squared is brought to you by Sociality Squared, a social media agency who understands the magic of bringing people together around what they value and love: http://socialitysquared.com.

Because it’s important to support artists, 10% of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to ArtsWave, a nationally recognized non-profit that supports over 150 arts organizations, projects, and independent artists.

Join Creativity Squared’s free weekly newsletter and become a premium supporter here.

TRANSCRIPT

[00:00:00] Jason Schneider: Much of what humans do is representational. That is, it is an abstract of a complex reality that is presented to consciousness. It’s true of mathematics, it’s true of language, it’s true of art. On the one hand, it’s very important to realize that it is through abstraction and representation that we can do many great things, but it is also very important to realize that in creating language and creating mathematics and creating art, we have delimited and selected from the complex and multifaceted reality that we experience through consciousness.

[00:00:49] All these things that we do, however great that they are, entail presenting and communicating something less than the totality. It’s important to remember in the quantifying of mathematics and all its glorious accomplishments that in quantifying anything or putting it into language, we have also limited it and have something that is not included. And that which is not included, as Emily Dickinson said in that poem, is vastly larger than that which we can communicate.

[00:01:26] Understanding that I think is humbling. And also. Very important.

[00:01:33] Helen Todd: Jason Schneider is a true modern day renaissance man with passions that include photography, motorcycles, poetry, music, and philosophy. As self admitted lifelong Leica maniac, Jason is also a camera collector, fine art photographer, writer, and photojournalist.

[00:01:52] Jason has written three books on camera collecting and an authoritative volume on wood burning stoves. He is currently writing a book with a working title Understanding Emily Dickinson, A Reader’s Guide to the Enlightened Master. Jason has built a long and prosperous career as a photographic journalist, where he’s held numerous prestigious positions.

[00:02:14] He is perhaps best known as the writer and editor who created the camera collector column, and rose through the ranks at Modern Photography Magazine to become its editorial director. After leaving Modern, he became the editor in chief of Popular Photography, the world’s largest imaging magazine, a position he held for over 15 years.

[00:02:35] Currently, Jason is a contributing writer for the Rangefinder Forum, in addition to Creativity Squared. I met Jason back in 2011, when my social media agency was launching and managing Leica Cameras’ social media channels. We worked with Leica for over five years, and Jason was Instrumental in writing questions and editing interviews for the like a camera blog, which we also managed.

[00:03:00] We’ve been colleagues and friends ever since from reciting points to thinking deeply about consciousness, art, and philosophy. I’m grateful to call Jason a dear friend and excited to share our thought provoking conversation with you today. In this episode, Jason expands on the articles he’s written for creativity squared, exploring AI and the question, “What is art?”

[00:03:24] You’ll also hear Jason’s perspective on human consciousness, art as representation, and the limitations of language and math. You won’t want to miss why Jason is in awe of Emily Dickinson, and to hear a few poems he recites, including one from his late and talented daughter, Heidi. Jason also points out what’s wrong with the premise of Descartes’ famous statement.

[00:03:46] “I think therefore I am,” and why cell phones are the best cameras ever made. Enjoy.

[00:04:00] Welcome to creativity squared. Discover how creatives are collaborating with artificial intelligence in your inbox on YouTube and on your preferred podcast platform. Hi, I’m Helen Todd, your host, and I’m so excited to have you join the weekly conversations I’m having with amazing pioneers in this space.

[00:04:18] The intention of these conversations is to ignite our collective imagination at the intersection of AI and creativity to envision a world where artists thrive.

Helen Todd: Jason, welcome to Creativity Squared. It is so great to have you on the show.

[00:04:42] Jason Schneider: Pleasure to be here. Thank you.

[00:04:44] Helen Todd: Yeah, I looked it up actually before I logged on. We actually met back in 2011 when we were both working on for like a camera and we brought you in as a writer for the, like a camera blog.

[00:04:57] Jason Schneider: Right.

Helen Todd: So it’s been very nice to get to know you over the years. And I wanted to just have you introduce yourself ’cause we’re gonna dive into a lot of like philosophical things today related to art and consciousness and ai. And I wanted our listeners from the outset to kind of understand why you are so well equipped to speak to these subjects from your love of Emily Dickinson.

[00:05:21] And so can you do a quick little introduction for us?

[00:05:23] Jason: I, you know, I majored in English literature. I’m not really a philosopher. I took a couple of college courses in philosophy. I was the editor in chief of Modern Photography and Popular Photography magazine. So in that sense, I’m a journalist and have been, and you know, but I’ve often thought about, you know, deeply about subjects like consciousness and art and creativity.

[00:05:50] And I am a fine arts photographer. I generally do my fine art photography in black and white on ancient film cameras. Although I do shoot digital as well. And I’m one of the few people who you know, is an old guy, old school and all the rest of that who thinks the cell phone is the greatest camera ever invented.

[00:06:13] So, you know, I connect those two things. I mean, photography is photography. And photography has a lot to do with art and a lot to do with consciousness and all these subjects are related. And that’s why I have thought abstractly upon this subject of consciousness and language and mathematics and what it really means, that sort of stuff.

[00:06:38] Helen Todd: and you’re also working on a book on Emily Dickinson too. And I know you do wonderful analysis of her poems. So maybe you could share why you love Emily Dickinson so much.

[00:06:48] Jason Schneider: Well, I started reading Emily Dickinson when I was about 14 years old and she’s in my opinion, perhaps the greatest American poet of the 19th century.

[00:06:59] And she expresses herself with uncommon concision and precision. When I read an Emily Dickinson poem, it absolutely tears me up. She comes across as intellectual and detached sometimes, but like Johann Sebastian Bach, you know, it’s all about passion. It’s all about emotion. There’s a great passion and emotion behind it.

[00:07:23] And you know, Johann Sebastian Bach, for example, created these glorious little Baroque machines, you know, if you listen to Toccata and Fugue in C major, you know, or something, but on the other hand what’s behind it is passion and emotion, which are the essential elements. in all art.

[00:07:45] Helen Todd: We’ll have you recite an Emily Dickinson poem a little bit later? There’s one in particular tied to AI that we’ll get to that.

[00:07:52] Jason: Well, yeah, there’s a lot of her stuff that’s attached to AI, actually. If you listen to Bach’s cello sonata no. 6, you know, you could say, gee, that was written in the 25th century because it’s out there.

[00:08:07] I mean, it’s like, and the same thing is true of Emily Dickinson’s poetry. You know, it’s not only eternal, it’s futuristic. I mean, even. Right. She dealt with all these modern concepts and in completely digested form. It’s astonishing.

[00:08:23] HelenTodd: Since you said that, I’m curious, can you get an example of one of her poems that comes to mind when you say that?

[00:08:30] Jason Schneider: One of my favorite poems by Emily Dickinson is about Paying attention in other words, it’s sort of a poem of regret, but now that I’ve attained this knowledge, I will do better going forward. It’s kind of that poem:

A cloud withdrew from the sky. Superior glory be, but that cloud and its auxiliaries are forever lost to me.

Had I but further scanned, had I secured the glow in an hermetic memory, it had availed me now, never to pass the angel with a glance and a bow, till I am firm in heaven is my intention now.

We go through life and we don’t notice, you know, be here now is what that is, what that poem is about.

[00:09:27] You know, you have this human consciousness, you use it, you know, really be open to experiencing the world. I think of driving into New York city when I was commuting from Rockland County into New York to go to work in the morning. And you have all these drivers driving over the George Washington bridge.

And it’s like they’re sleepwalking, you know, and there’s New York city, this magnificent vista, you know, and nobody cares and nobody is noticing it.

And it happens every day, and there it is. And you have the gift of human consciousness, use it. Open yourself to experience. It will avail you now. If you take this in, it will be of use.

Right? Avail, the basic concept of avail is use. It’s not just, don’t be a passive observer. Be there, right? And so that’s one of my favorite. Poems by Emily Dickinson. Simple, you know, but profound.

[00:10:36] Helen Todd: I’m so excited to have you on the show. And for our listeners and viewers Jason and I talk on the phone often and I get to hear him recite poetry.

[00:10:45] So, it’s nice to get to share this with the community here. And in addition to the work that we did with Leica Camera together, goodness, we worked we did daily blog posts, interviewing photographers for like five and a half years. Jason is currently writing some blog posts for Creativity Squared, which we’ll link to in the description

[00:11:05] And that you can also read, but we’ll go into some of the topics that we dive into. And the first blog post, which kind of continues where we’re starting is what is art exploring humanities’ defining passion. And I thought I would just like, let you kind of expand and speak to this. One of the lines that you wrote is in other words, art is a form of existential and emotional communication.

[00:11:32] So can you dive in and tell us what the article was about?

[00:11:36] Jason Schneider: “What is Art?” is one of those, you know, eternal questions and you say, really, you’re going to talk about what is art? I mean, it’s like, what is the meaning of life or something? I mean, it’s a huge topic. But one of the signal and identifying features of human consciousness is the ability to abstract, to take significant details and present them in a symbolic form. Language does that, mathematics does that.

All these human endeavors concentrate the consciousness and point it in a specific direction. And people have created art since Homo sapiens trudged along this planet, perhaps 300,000 years ago, when the first Homo sapiens appeared.

[00:12:21] Right? You can take a look at the cave paintings of Lescaux, France, right? I mean, they’re magnificent. They’re, I mean, some of these things, they’re so vibrant and alive and it’s almost like the decisive moment, you know, of Henri Cartier-Bresson representing an animal on the walls of a cave.

[00:12:41] And it’s such a very human thing to do. You know, now maybe they were trying to exert power over the animals or something, but they communicated their world to us in something done 17,000 years ago. You know, you can’t determine what their motivation is, their specific motivation, at this point in time, but that urge to represent.

[00:13:06] Something of one’s consciousness is a very human thing. Animals possess certain aspects of human consciousness in prototypical form, but animals don’t consistently create art, for example. You know, you could show examples of some animals that do things that appear to be, you know, in mating displays and all the things.

There are creative aspects to those things and individualistic aspects, but abstract reasoning is really humans on this planet anyway.

Helen Todd: One of the reasons why I wanted to bring you on the show is your name came up on a recent interview with Walter Werzowa.. and he asked me the question, you know, what drives creativity?

[00:13:49] So we started kind of diving into that. And for him, it’s all about the intentionality and choice, which I know you wrote about also in the blog post called “All Art is Representation”, I think is the title. Yeah. So. Tell us about what you meant by all art is representation and where human choice comes into the question of what is art?

[00:14:11] Jason Schneider: Representation is simply distilling a simulacrum, the essence of one’s experience, you know, and as a photographer, specificity is everything and and that’s choice. So if I have a photograph, usually photographs are square or rectangular. They can be oval and round and stuff, but typically they’re squares or rectangles.

[00:14:40] There’s a frame that I placed on my reality, my experience, and looked at something that was meaningful to me. Look at this, rather than that. You’re taking a specific thing out of the great tumbling reality around you and requesting, in, in a sense, that the viewer pay attention to this particular thing.

[00:15:08] It’s a representation, in the larger sense, of how you view the world, or specific aspects of your experience. I suspect that there are other animals that know that they are going to die. Elephants, in particular, have burial rituals and all sorts of things like that. Burial, but, you know, death rituals.

[00:15:31] And so there is some sense that the animals have that, that they are mortal, but only humans have this abiding sense of their own contingency. And the fact that they are here now and gone tomorrow, and so they want to leave something of themselves. And it’s it’s a, it’s an urge.

[00:15:54] You could say. It’s, you know, “une tentative d’immortalité” an attempt at immortality. And it’s the residue. It’s of your life and consciousness presented. You know, individual, visual form or as a Shakespeare play or as you know, Bach Beethoven’s 9th symphony. I mean, it’s it’s a it is a representation of one’s own experience.

[00:16:20] And it seems to be a drive to do this. Because humans have always done it. I mean, historically humans have always created art ever since they could be called human. You have jewel jewelry, you know, that is, you know, a hundred thousand years old or 30, 000 years old anyway. Right.

[00:16:44] And It was created by this person. What does it mean? You know, that somebody put all this effort into creating this ornate and lovely and beautiful object. Right? Maybe it was to adorn an upper class person, but there’s more to it than that. It’s a representation of a mode of being and a civilization and a society and an individual and their relationship to that society.

[00:17:12] So it’s everything. I mean, I take a look, you at a camera. I mean, I’m a camera collector for better or worse, right? I have a camera. It’s a Conica rangefinder camera from 1948. And I look at this thing and I say to myself,

“Well, you know, it has certain primitive aspects to it. It’s got an old fashioned kind of winding mechanism. But basically, it’s a beautiful object and the fundamental elements of it, the rangefinder, the lens the way it works, are really magnificent.” And you take a look at this thing and it says, made in occupied Japan.

[00:18:05] That country was in a devastating situation in 1948 and they created this brilliant object. However compromised it may have been in what was available at the time. It’s not a camera. It’s triumph of the human spirit for the Japanese to have created this thing when the country was excuse my expression on the balls of its ass.

[00:18:32] All right. In 1948, right? And so you know, there is art in many things that, that humans do, you know. I mean, shaker furniture was created for strictly utilitarian purposes, but it’s fine art.

[00:18:52] Helen Todd: One thing that we’ve talked about, and I know that you included in one of the blog posts is in terms of like art being representation of our lived experiences.

[00:19:02] Anything outside of our mind that we create in essence is art or representation because we just absorb everything through our senses. So, any expression is just our representation of our reality, more or less. Did I capture that sentiment right?

[00:19:19] Jason Schneider: Well, you capture the sentiment but the thing is representations and abstractions are essential elements in the human experience.

[00:19:31] The we had a math teacher. It was Math 101 at NYU. And he was a real character, Professor Jacobson. He was an old fashioned math teacher. The kind of guy who could take his arm and go, whoop, and draw a perfect circle just with a sweep on the blackboard. Right. And so we sat there and it was math 101, and you were expecting, you know, a little advanced algebra, maybe introduction to calculus or something.

[00:20:05] And he drew something on the blackboard. And what he drew was a gorgeous three quarter perspective line drawing of an elephant. And he said, “ladies and gentlemen, what is that? And people said, ‘well, it’s an elephant.’ No. ‘Well, it’s a drawing of an elephant.’ No. ‘Well, it’s it’s calcium carbonate on graphite.’

[00:20:36] No. And we kept on saying, so finally ‘we said, okay, we give up.’ What is it? And he said, it’s a teacup. And we said, ‘what, how can you say that? ‘Because I define it as a teacup.” Mathematics is the assigning of value to abstract symbols for the purpose of calculation or other things. It’s in other words, we take.

[00:21:06] The complex reality, and we simplify it by quantifying it. And that’s the essential nature of mathematics. All those numbers that you see before you, which some people call Arabic numbers, but really originated in India.

[00:21:24] They’re actually Hindu numbers, if you want to put it that way. People think of one or two as gee, that’s real. It’s one or two. No, it’s an abstraction. It stands for something that will benefit from the ability to simplify and calculate. So even though mathematics cannot possibly capture all the subtlety of perceived reality, it takes a specific element and represents it.

[00:22:03] And in a certain way that it can be used for calculation and all God bless science, you know, and mathematics, but it’s all based on this fundamental symbol making or representation. Representational characteristic that is the, is one of the essential elements in human consciousness.

[00:22:29] Language is the same way, right? Voldar, the ancient cave man, right? Is trying to warn his buddy watch out for the saber tooth tiger. And so he says, “Joe, there’s a saber tooth tiger behind you.” Right? Is an abstract of the reality. It conveying the essential elements necessary to preserve Joe’s life.

[00:22:59] Right. And that’s what language does. It takes complex reality and it lets you say.. you can’t say everything all at once. Otherwise, you will be saying nothing. So what language does is allows us to say something about something rather than encompassing the whole thing, but in so doing, it simplifies it and abstracts it, right?

[00:23:28] That’s the essence of language and the poem. that I was talking about by Emily Dickinson. It requires some explanation because, you know, usually what you do with a poem is you like to have it flow over you. The way to appreciate a poem is read it aloud. Let it flow over you. Don’t try to analyze it. Just listen to it.

[00:23:53] Listen to the music. Poetry is the music of language. So listen to it, right? And that’s the first thing you do. But eventually you want to say, well, what the heck is Emily talking about? Right? And so, this poem is a very simple one line poem and it’s utterly profound. And it’s Emily Dickinson, the master of concision and precision in language.

[00:24:24] This is a poem about, that is ironically, and paradoxically, about the inherent limitations of language. Right? So, she says, she uses synecdoche, which is where you have one element stand for a larger whole. For example, she talks about the lip. She’s not talking about the physical lip. She’s talking about the faculty of language and speech.

[00:24:51] Right. And she very cleverly says mortal and divine. And while she’s using the term divine, not in, you know, the divine principle or something, she is using divine in in the sense of divination, to suss out something. Right. So she says,

“could, (it’s conditional), mortal lip divine

the undeveloped freight in a delivered syllable

‘Twould crumble with the weight.”

[00:25:25] So, the speech is taking this thing, like a semi tractor trailer, and conveying it to the recipient. put mortal lip to find the undeveloped freight of a delivered syllable. So, freight and delivery, right? So what she’s saying… Is if the faculty of human speech, if speakers could understand that what cannot be communicated in speech or even an element of speech, like a syllable, right?

[00:26:00] Is so vastly greater than what can be communicated. So, paradoxically, she is communicating something that stands for the limitations of language and poetry and everything else, because the vastness of consciousness and experience can only be distilled and what is left out. Is enormous.

[00:26:30] Right.

[00:26:31] Helen Todd: Thank you so much for sharing that. And one reason why I just love our conversations about this is specifically in applying that or thinking about that related to AI is how these at least, specifically generative AI models, but how these machines are trained is based on math and based on language and what you just said, the limits of language gives the limitations to these machines to really capture the full human experience too, which I find very fascinating.

[00:27:02] Jason Schneider: Well, A lot of our experience is successfully enshrined in language. In other words, just because it can’t communicate everything doesn’t mean that what it can communicate isn’t very great or very important. And that’s why an AI program that’s properly trained on scraping the right sort of of verbal material can produce something extraordinary.

[00:27:34] My dear friend, Lisa Hewitt and I created some really outstanding images by prompting an AI system, which happens to be Mid Journey t to produce a an ancient or an old fashioned image in a certain style of a certain kind of classical, old fashioned subject and what it turned out was, it was incredible.

[00:28:01] It stood up. I mean, you could just say, wow, that’s a really great photograph. But of course it’s not a photograph. It is a representation of a verbal command that is based on analyzing the data in the AI data dataset. Right. And it’s amazing what can be achieved.

[00:28:21] And she also wanted to write a story about something. A guy with a lousy sense of humor, but he was the boss. And so when he told jokes, everybody laughed. And he assumed that he was this great comedian and he set up this comedy club and the audience was listening to the stuff. He was delivering these terrible jokes because he was really a rotten comedian, right?

[00:28:45] And and everyone was stoned silent until one person started laughing. And then everybody started laughing because the joke was how how ridiculously bad his humor was, right? And so you could laugh at the ineptitude of it all, right? But the AI wrote this little fairy tale type thing.

[00:29:08] It was very sophisticated. It had this sort of artless quality to it of a fairy tale, and yet some of the observations about this person were very astute and sophisticated. And, this is an AI product. Being turned out on a command. So, you know, the upside potential for this is amazing.

[00:29:31] But on the other hand you know, the writer’s strike and the actor’s strike right now are illustrative of the fact that it can also be used to supplant, to take jobs away from people. I mean, literally you know. If it’s good enough to write a script, you know, what’s the writer going to do?

[00:29:54] Right.

[00:29:55] Helen Todd: Well, in one of, well, there’s so many kind of worms and paths we can go down.. in, in one of your articles, you put forth the thesis that as long as there’s any type of human consciousness or choice in the selection, or even I think in that one article, even prompting to create images is enough to call it art because a human touch goes into the prompt itself.

[00:30:20] Jason Schneider: Well, the answer is that the AI images that. Lisa and I created using a verbal prompt I would have made a big poster size enlargement and put it on display. It was that good, right? And I think that part of the quality of that presentation was..what’s the prompt? And when I took a look at the, that the little fairy tale created for Lisa with her verbal prompt, I would take a look at that and say, well, you know, that’s pretty good.

[00:30:58] But I think I can polish it and make it even better. And I think if I were to publish that, I would take, what AI spit out and then I would add the human element and bring it up to a higher level. Okay. So, AI can be part of the process of creating art. There’s no doubt about it. And the ownership is still by the artist, not by the AI system.

[00:31:28] Helen Todd: And can you share the thought experiment that you wrote about in terms of the security camera? Because I thought that was like an interesting thought experiment of the human touch being part of art and choice.

[00:31:41] Jason Schneider: Many banks set up security cameras in areas where there’s an a t m or something like this.

[00:31:50] And of course they generally destroy the results of their surveillance, unless something happens, you know, unless somebody tries to break the ATM machine or or or something, right? Or tries to rob the bank, right? But on the other hand somebody who who is in charge of that imagery captured by an automatic camera. Somebody set up the automatic camera.

So, the angle of view that it subtends, right. And the location, and the timeframe and the lighting and everything else are all decision points. And then some poor SOB has to go through all this footage of nothing in particular to find a decisive moment.

[00:32:50] And I was saying, well, what if somebody standing by the ATM you know, a husband and wife are having an argument and the and the wife took a hundred dollar bill and smashed into the face of her husband with a hundred dollar bill. That would be an interesting photograph, right? And so, if the person in charge of reviewing the footage selected that image that’s an act of CO activity.

[00:33:18] You have this automatic thing and it’s spitting out this thing. Well, first of all, you’ve set up parameters. So, it’s not simply random. There is a human element in setting up the parameters of the surveillance system. Then there’s the choice of which frame to exhibit, you know, as a sort of madcap funny image.

[00:33:40] And of a wife smashing her husband in the face with a hundred dollar bill. Yeah. So, selectivity is one of the essential elements of art. And certainly as a photographer selectivity is everything. Right. I like to say, I like to shoot fine art portraits and in black and white on ancient, mostly medium format film cameras.

[00:34:10] And what I like to say is the subject is everything. I’m only the photographer.

[00:34:15] Helen Todd: I love that. Well, and it’s interesting because this is being debated in the courts right now where prompts can’t be copyright, but the curation and the order of images generative AI models can be copyright.

[00:34:30] So it’s a, you know, it’s an interesting debate happening in courts right now too.

[00:34:35] Jason Schneider: Well, you know, it’s interesting. I was thinking to myself when I took a look at this magnificent image of a coal district. Yeah. In what looks like a 1920s or early 1930s photograph, and the composition was really lovely, and there were people in it.

[00:34:51] And this was this totally AI generated thing. We used Mid Journey. Now, if I were to publish that picture or exhibit it in a gallery, I would say, Jason Schneider and Lisa Hewitt with Mid Journey. Okay, I would credit the AI system as part of the process, right? The question is do I own that image?

[00:35:18] Could I could I sell that print that I made, right? As my work and sign it.? That’s a legal question. That’s not really a philosophical question.

[00:35:29] Helen: Well, and one thing that you wrote in one of the articles, just I think that was the will AI kill photography or..

Oh, you wrote an article called “AI and the future of photography, the ultimate tool or the weapon of its mass destruction” Provocative sort of title, but you kind of talk about the history like when photography was invented, a lot of people thought it was like the end of painting and it was very controversial.

[00:35:56] And then when Kodak came out, but it really photography is always kind of democratized image making to a certain extent.

[00:36:03] Jason: Well, the great contribution of George Eastman was that he was a marketing genius and he realized that photography at the time in 1888 was, you know, sort of an arcane practice, but people in smelly dark rooms with toxic chemicals, especially the daguerreotype process, which involved mercury and you know, and so he felt that photography was a mass market phenomenon, that everyone should be able to take pictures, and of course, he would be happy to sell ’em a camera, right?

[00:36:39] And film! And film of course was the razor blade off of Eastman Kodak’s marketing strategy. You know, he could afford to sell the camera at a break even. And with the idea that people would be using film in it. And Eastman Kodak made its fortune on film more than anything else, right?

[00:37:00] But that’s entirely true. I mean, photography in the late 19th century, there were artists, painters in particular, who felt that it would spell the death of painting. And what it did to a certain extent is transformed representational painting into much more emotional, personal, abstract kind of art.

[00:37:32] You know, you talk about Van Gogh or Cezanne or something like this. And it was, in other words it made… painting into something else and not just representation, you know, you’ve got to admire the people, you know, like Caravaggio and Titian, you know, these great artists who did the most gorgeous representational art.

[00:37:55] But so photography, all these artists were afraid that the photography was going to take over. Any fool can work out with a camera and achieve proper perspective and three dimensionality and everything else without having to you know, understand perspective or anything.

[00:38:12] It was all automatically done for them. And it’s going to destroy art and we’re going to be out of a job. Being out of a job, I think is one of the primary complaints of people with any new technology. There are people in the UAW (United Auto Workers), right, who are afraid of electric cars that they’re going to, they’re going to take over and we’re going to lose jobs.

[00:38:38] They’re going to require a few, fewer people to manufacture them. Maybe it’s all going to go to China …booga, booga, right? And so, a lot of the complaints about new technology in general are about automation, about AI, about electric cars, but all these things people are afraid that changing the paradigm is going to render them irrelevant.

[00:39:06] Helen Todd: Oh, you kind of spoke to it that what the point and shoot camera did was really democratize photography and more people just, you know, was able to make more photographs. And the same thing with, you know, I would say the iPhone camera was very similar in just the explosion of now everyone’s a photographer with with whatever phone that they have in their pocket.

[00:39:26] Jason Schneider: The iPhone camera is a marvel and I am all for the iPhone camera. I mean, I was in a situation I know there are some dear friends of mine where the husband is slowly dying of cancer and it’s a very sad thing. He has three young children, and one is a teenager, but the others are younger.

[00:39:54] And you know, it’s a personal tragedy and I saw him with his wife, in this place and they both were joyous and they were together, and you know, you could see that he was, you know, suffering but they managed to transcend it and they were joyful. And I didn’t have my film camera with me.

[00:40:20] So I took out my cell phone and took this picture, right? I have an iPhone 14 plus and I took this picture and it’s a perfectly wonderful picture. I sent it to them and they made a big copy of it and are displaying it, you know in their home and so, one of the great rules of photography is the best camera is the one you have with you.. and the cell phone certainly answers that that meets those criteria.

[00:40:49] So, you know, I’m all for the cell phone camera.

[00:40:53] Helen Todd: I know I take a bazillion photos with my iPhone and. Should probably get out my Leica and shoot more with it.

[00:41:02] But I have, I think over a hundred thousand photos on the one that I carry with me all the time.

[00:41:06] Jason Schneider: The interesting thing though, is that the process of photography, you know.. The classic statement is, oh, it’s not the camera, it’s the person behind the camera that makes the picture. Well, that’s a truism, you know, and you can’t argue with it, as far as it goes, but…

[00:41:28] The experience of shooting a picture is quite different if you are using an 8×10 view camera, a two and a quarter, single lens reflex or an iPhone or a point and shoot 35 millimeter camera. The human interface between the camera and and the photographer and the camera and the subject is different.

The difference is visible in the type of photographs that are produced. So the camera, although the photographer is clearly the most important element in the equation, the camera is not irrelevant. And it does shape the result that you get. If I shoot pictures with a Rolleiflex, they look qualitatively different.

[00:42:19] From ones I shot with an iPhone.

[00:42:22] Helen Todd: I think another interesting topic related to cameras, like one, almost all are involves tools. And when we like, talk about AI being another tool, but specifically within the Leica camera community, which, you know, you and I are both well deep into. A lot of Leica photographers talk about the soul of the camera and assign the technology, having a soul to it, which I always find like really interesting when I hear that from like a photographers.

[00:42:50] Jason: Well, put it this way, different cameras have different characteristics. You ask yourself the question, do they affect the final results? And as I would say, they do. Whether that means that the Leica has a soul any more than a Canon, I’m not sure. You know, but I think cameras.. I think soul is a little bit grandiloquent, you know, to assign to a piece of equipment, but they do have distinctive characteristics that definitely shape the kind of output.. artistic output, if you want to call it that that, that is produced. So shooting with a Leica is a different experience than shooting with a Nikon single lens reflex or a Sony mirrorless camera. It’s a different, it’s a different experience.

[00:43:46] That’s why. Even though the Leica M3 was introduced in 1954. There are still digital versions of what is essentially an M3. That’s that still exist. Whereas the the possibilities of of a mirrorless camera or a single lens reflex might be greater than that of a rangefinder camera in a certain way.

[00:44:16] It’s distinctive characteristics are appreciated by photographers because they instinctively know that it affects their approach to the subject, and it affects the way they articulate their vision. It’s a tool through which you articulate your vision. And so its characteristics are not irrelevant, even though it is the consciousness of the photographer behind the camera that is the key element.

[00:44:42] Helen Todd: I know we’re getting a little bit close to time for the interview. But, I thought that we might tease one of the blog posts or articles that you’re working on now about consciousness and what Descartes said about, I think therefore I am. So, do you want to share a little bit more about what you’re thinking about and working on for an upcoming article?

[00:45:04] Jason Schneider: Well, the thing about Descartes is that he was trying. To create a situation where he was a disembodied consciousness separated from mere physical you know, realities and exigencies. So, he closeted himself in a room and thought about thinking and thought about what is this consciousness that I am.

[00:45:32] And so he came up with this thing, Cogito Ergo Sum, in Latin, which is I think, therefore, I am… much more elegant than Latin and the problem is that his premise was faulty. He was not a disembodied consciousness. He was supported by people who took away his waste and brought him food and water and saw to it that he could live in that space. And so he was in the immortal words of WB Yates, William Butler Yates, he was fastened to a dying animal as we all are fastened to a dying animal. It’s a kind of grisly image. And it’s also incorrect because the body is not a mere body. Okay. The body is inextricably involved with the soul, if you want to put it that way, which is to say the human consciousness and the human experience.

[00:46:29] So, the notion that there’s this thing in your head and in your brain, and it’s all your thoughts and your feelings and everything else, and then there’s this… body that sort of supports all this. Well, you know, it’s nonsense. They’re inextricably a single entity. It may be useful for a philosophical discussion to distinguish between the body and the soul.

[00:46:51] Neither of which is very well defined, I might add. But it, it doesn’t actually reflect the reality of the situation, but to get back to what you were talking about the refresh my topic here.

[00:47:07] Helen Todd: Well, one of the reasons why Jason just pitched this idea to me the other day and you know, one of the things I find interesting with the onset of generative AI capturing everyone’s imagination this year is that it lends itself to all these existential questions of what does it mean to be human? So all these questions about consciousness and these philosophy questions come up.

[00:47:31] So that’s why I was like excited to hear your thoughts on it.

[00:47:34] Jason Schneider: What I said was the problem with Descartes formulation is the fact that it is. kind of verbal sleight of hand. It is in fact self referential. In other words, the only one who could determine whether I am is me because I think.

[00:47:51] Helen Todd: Well, one of the things that you wrote about in one of your articles too, just about what is art, is that to a certain extent, a social element to it as well in terms of other people helping designate that this is art.

[00:48:02] And in the same way, you know, one thing that I don’t like about Descartes statement is it’s so individualistic versus more of the one of my favorite quotes by Einstein is actually a letter of condolence where he’s like, we need to expand our limitations to encompass like the whole of consciousness.

[00:48:20] And I think Descartes’ statement from my perspective is too individualistic in that sense

[00:48:25] Jason Schneider: I sort of had a nasty send up of that, and my own was I die, therefore I must have been. Right? In other words, my existence is certified by those who remain after my demise. And I think, you know, although it’s, it was done in a puckish sense of humor.

[00:48:49] It’s, I think it’s true that our existence we are not the ones who affirm. our existence in a in an existential way. Maybe we do, but there’s a lot more to it than that. And namely that we are social beings and our existence is created and shaped and affirmed by others and by the society in which we operate.

[00:49:16] Helen: So Jason, if you want our listeners and viewers to remember one thing from our conversation about AI, art, consciousness or Emily Dickinson or anything we talked about what’s the one thing that you’d like them to remember and walk away with?

[00:49:33] Jason: Well, I think that much of what humans do is representational, that it is an abstract of a complex reality that is presented to consciousness.

It’s true of mathematics, it’s true of language, it’s true of art. On the one hand, it’s very important to realize that it is through abstraction and representation that we can do many great things. But it is also very important to realize that in creating language and creating mathematics and creating art, we have delimited and selected from the complex and multifaceted reality that we experience through consciousness.

All these things that we do, however great that they are, entail presenting and communicating something less than the totality. It’s important to remember in the quantifying of mathematics and all its glorious accomplishments, that in quantifying anything or putting it into language, we have also limited it and have something that is not included.

[00:50:50] And that which is not included, as Emily Dickinson said in that poem, is vastly larger. And that which we can communicate, understanding that I think is humbling and also very important.

[00:51:06] Helen Todd: That’s beautiful. And such a great note to end on and have everyone reflect on presence and just the beauty of the complexity of the reality that we experience.

[00:51:16] So thank you for sharing that. And before we sign off, I also, I’m holding a book that was just listening on the audio portion with poems from your daughter called, I Am Here, but I am not. So, I thought give you the opportunity to share with our readers and viewers of this book and the beautiful work of your daughter.

[00:51:35] Jason Schneider: Well, Heidi, of course, die tragically at age 34 of cancer. And she was a an intuitive poet who started composing poetry when she was 11 years old and created an amazing body of work. It’s not as large as it could be, but it’s significant. And I compiled it into a book, more or less told her story and just let her..I mean, just present her work and it’s it’s an amazing book and she was an amazing person and so, I mean, it’s a tribute to her and and I was very glad I was able to get it out there.

[00:52:21] Helen Todd: is there a poem that you would like to share that Heidi wrote?

[00:52:25] Jason Schneider: Well, this is sort of the title poem. That’s where I derived the title of the book from something that she wrote on an envelope two months before she died. So it’s called Poem on an Envelope. I am here, but I am not. My heart tried letting go of its grievances, one by one, like letting go of balloons, flying high until they disappear.

[00:52:56] May the space which once I occupied by a sweet one be filled with the things dearest to me. Forsythia, gingerbread cookies, and absolute wonder. Each thing felt in my small body as infinite as anything could be. Cloudless skies, dusk, the exalt smell of the forest. Lay me down to that.

[00:53:26] Helen Todd: I have chills. Thank you for sharing that Jason.

[00:53:31] Jason Schneider: You’re welcome.

[00:53:32] Helen Todd: And I’ll be sure to put the link to the book in the description and the dedicated blog post. So anyone who would like to see all the poems and support you where they were they can find it. Thank you so much, Jason. I’m so glad for it was actually Christian Earhart that originally he was the.

[00:53:51] Head of marketing for Leica Camera USA that brought me in and I’m so glad he did because it’s opened up this whole world of meeting amazing people through Leica Camera. And you are, you’re certainly one of them. And I’m so glad that working together has turned into this friendship. And to today’s conversation and all the ones that we will have,

[00:54:10] Jason Schneider: thanks so much for the compliments.

[00:54:12] And I am honored to be your friend.

[00:54:14] Helen Todd: Likewise. Jason, it’s been an absolute pleasure, so thank you so much.

[00:54:17] Jason Schneider: Thank you.

[00:54:21] Helen Todd: Thank you for spending some time with us today. We’re just getting started and would love your support. Subscribe to Creativity Squared on your preferred podcast platform and leave a review. It really helps and I’d love to hear your feedback. What topics are you thinking about and want to dive into more?

[00:54:37] I invite you to visit creativity square.com to let me know. And while you’re there, be sure to sign up for our free weekly newsletter so you can easily stay on top of all. the latest news at the intersection of AI and creativity because it’s so important to support artists. 10 percent of all revenue Creativity Squared generates will go to Artswave, a nationally recognized nonprofit that supports over 100 arts organizations.

[00:55:01] Become a premium newsletter subscriber or leave a tip on the website to support this project and Artswave and premium newsletter. Subscribers will receive NFTs of episode cover art and more extras. to say thank you for helping bring my dream to life. And a big thank you to everyone who’s offered their time, energy, and encouragement and support so far.

[00:55:23] I really appreciate it from the bottom of my heart. This show is produced and made possible by the team at Play Audio Agency. Until next week, keep creating.